Under the shadow of nightfall on October 16, 1859 (that’s 160 years ago this fall), famous (or infamous, depending on who you ask) abolitionist John Brown led 21 men across the Potomac River into the Virginia village of Harpers Ferry. Brown, an ardent abolitionist, believed that slavery could only be ended through violence- so he was building an army. He brought his tiny army of 21 to Harpers Ferry to collect weapons from a federal military arsenal in town, and to hopefully recruit the many free black men in the vicinity to their cause.

Initially the raid progressed smoothly. Brown’s men cut the local telegraph wires, quickly took over the rifle factory, and began accumulating hostages. Unfortunately, by the end of December, Brown and 16 of his men would be dead.

Seven of the men involved in the raid on Harpers Ferry came from Ohio, not including John Brown and his sons. Brown was born in 1800 in Connecticut, but came with his family to Ohio at a young age. Here Brown’s anti-slavery father planted lifelong abolitionist beliefs for Brown. As an adult, Brown moved his family around in the pursuit of abolition. While it is certain that his time in Ohio shaped young John Brown, it is often forgotten that he grew up in the Buckeye State.

In 1855, Brown moved to Kansas, where he met and befriended fellow Ohioan, John Henri Kagi. Kagi, the descendant of Swiss Mennonites and the son of a blacksmith from Shenandoah County, Virginia, was born and raised in the Ohio town of Bristol, in Trumbull County. Born in 1835, the precocious young Kagi was sent to Virginia as a teenager to attend an academy and begin teaching. By the age of 19, Kagi had made his abolitionist beliefs clear to the local community and was forced to return to Bristol. Here he began teaching again and attending law classes.

Everyone who knew Kagi described him as brimming with knowledge and intellectual curiosity. As one friend, George B. Gill once said, “He was full of a wonderful, enduring vitality….All things were fit food for his brain.” Approaching his abolitionist views with a great fervor, Kagi became involved with the Free-Soil Party in 1854, traveling to Kansas in 1856, where he met John Brown.

Beginning in 1854, the territory of Kansas entered a time of confusion and violence known as “Bleeding Kansas.” In that year, Congress parted with their 1820 Missouri Compromise and passed the Kansas-Nebraska Act, declaring that laws regarding slavery in the Kansas and Nebraska territories would be decided by their residents. In reaction, white settlers on both sides of the issue of slavery raced to the West. John Brown was well-known for his part in the fighting that ensued.

Kagi was also in Kansas to promote his abolitionist politics. He wrote for many national newspapers and was even arrested for espousing his ideals. Kagi and Brown became friends in Kansas, traveling in many of the same abolitionist circles. Kagi would serve as Brown’s adjutant general at Harpers Ferry.

Also briefly in Kansas in 1856 was another Ohioan, Barclay Coppock. At the time, Coppock was only about 17 years old. Although he did not cross paths with Brown or Kagi, Coppock was infected with the abolitionist spirit, bringing it back to his older brother Edwin in Iowa.

The Coppock brothers were both born in Winona, Ohio, in Columbiana County. After their father passed away early in their lives, they were raised by John Butler. The two boys were abolitionists from a young age, embracing the Quaker morals that surrounded them in their home town.

As teenagers the Coppock boys moved to Iowa to be with their mother. It was here that they met John Brown as he passed through in early 1859, transporting people who had been enslaved in Missouri to freedom. That summer, the two boys bade their mother goodbye, despite her fears of the violence they would encounter, and traveled to Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, to meet Brown’s growing army.

Back in Ohio, a man named Dangerfield Newby was also packing his bags to join John Brown. In his early thirties, Newby would be one of the eldest men in Brown’s group of raiders. Newby was born in Virginia, the son of an enslaved woman and a local slaveholder. Newby’s father decided to free his children, including Dangerfield, and send them to Ohio.

When Newby was sent to Ohio, he was separated from his wife and children, who were held in bondage by a different slaveholder. Newby began raising funds to buy their freedom, but when he traveled to Virginia with the money in hand, the slaveholder decided to change his price.

Newby was still working to raise additional funds to meet these devious demands, when he met John Brown as he passed through Ohio. Deservedly angry and ready to act, Newby slipped away to join Brown’s growing movement.

Meanwhile, on Ohio’s Northeast Coast, three more men were planning to join Brown on his raid.

One of these men was Sheilds Green, a formerly enslaved man, born in Charleston, South Carolina. Green escaped bondage and made his way North to Ohio, settling in Oberlin. Green was a widower when he fled, but he had a child that he was forced to leave behind in Charleston.

Green, known as “The Emperor” because of his large stature, became friends with Frederick Douglass. Before his raid, John Brown met with Douglass who declined to be involved, believing Brown wasn’t following the correct path to abolition. It is said that Green was at this meeting and chose to follow Brown despite the dangers.

Also living in Oberlin, Ohio, at this time were Lewis Sheridan Leary and John A. Copeland. The two men were about the same age, but Copeland was a sort of nephew to Leary. Leary’s sister was married to Copeland’s maternal uncle.

Leary, and his sister, were born in North Carolina to a free black family. He was well educated as a young man, and very interested in music. Despite this interest, Leary took on his father’s business of harness making. Leary came to Oberlin as a young man, following his sister. He worked in Oberlin as a harness maker and married Mary Patterson, an Oberlin graduate. The two had one daughter.

John Copeland was also born in North Carolina to a free family. He moved as a young boy to Oberlin with his parents. He attended Oberlin College in 1854-1855, where he became involved in the Oberlin Anti-Slavery Society.

Leary was also a member of the Oberlin Anti-Slavery Society. Accordingly, in 1858, both men were involved in the rescue of a fugitive slave named John Price. It seems that participation in the well-known Oberlin-Wellington Slave Rescue only cemented fiery abolitionist feelings for both men.

Most sources believe that it was Lewis Sheridan Leary who first met John Kagi as he came through Oberlin looking for new recruits for John Brown’s growing movement. Interested in what Kagi was saying, Leary spoke to Copeland about the opportunity. Without a word to their families, the two men slipped away and made it to Brown’s hideout just in time, arriving on October 12th.

In the spring of 1859, John Brown rented a farmhouse, known as the Kennedy Farmhouse, just outside of Harpers Ferry. He gave a false name to the neighbors, who would have recognized him as the violent abolitionist from out west. (Today this would not have worked, but in 1859 it was not uncommon to read all about a famous individual without ever seeing an image of them.)

It was at the farmhouse that Brown planned and plotted, as his fellow raiders arrived and got to know each other. Here Kagi was often deep in thought, wandering “about with a slouched hat, only one leg of his pantaloons properly adjusted, and the other partly tucked into his high boot-top.” Brown’s daughter in law, Martha and his daughter Annie lived in the farmhouse and took care of domestic tasks. Many of the men lived in the attic so that locals would not notice the suddenly growing population of the farmhouse.

John Brown spent that summer trying to convince his men to take on an impossible task. They knew that to raid Harpers Ferry was to approach a certain death. Before Leary and Copeland had even arrived from Oberlin, the men agreed to the plan. As Kagi had said a year earlier, “the result will be worth the sacrifice.”

John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry started out well. The raiders came into town, cut the telegraph wires, and took the night watchmen hostage. They took the arsenal and rifle factory, and began to take more hostages from the village.

Unfortunately for Brown and his men, shots eventually rang out, and word spread throughout the town that abolitionists had arrived. Local men with weapons began to surround the arsenal. A train also came through the village, ruining Brown’s control of outside communication. He let the train pass, which allowed its riders to let others know that the village needed assistance. Soon the Marines would arrive.

Before reinforcements had a chance to get to Harpers Ferry, Brown could have escaped with a cache of weapons from the arsenal and the lives of most of his men. Unfortunately, he delayed, although no one knows why. It is believed he was waiting for local slaves to rebel and join him. However, not knowing that Brown was coming or what his intents were, most local slaves and free black men were hesitant to join him in the confusion and violence that ensued.

The first of John Brown’s men to fall at Harpers Ferry was Dangerfield Newby, shot by a local farmer who had come to put down the rebellion. Standing alongside Newby was Shields Green, who quickly took down the farmer.

Newby was left where he fell in the street for over a day, his body abused by angry local whites. When Newby’s body was finally recovered, it was discovered that he had been carrying letters from his wife that day, as he was still working to free her from slavery. In these letters she wrote of his plans to free her, saying, “there has been one bright hope to cheer me in all my troubles, that is to be with you, for if I thought I should never see you, this earth would have no charms fo me.”

Lewis Sheridan Leary and John Copeland were assigned to guard the rifle factory under John Kagi’s command. Certain he could not hold the factory any longer, Kagi led his men to retreat across the Shenandoah River. Kagi and Leary were gunned down as they tried to leave the growing battle. Copeland was captured.

Edwin Coppock was positioned in the arsenal with John Brown, where he stayed until forced to surrender to federal forces that had been called in to calm the uprising. It is said that while he was in the arsenal, Coppock had a clear shot at the leader of these federal forces- Robert E. Lee. Had he shot, he could have fatally wounded the future Confederate general. Comments from Coppock after the raid suggest that he was hoping to fight for his cause with as little bloodshed as possible, meaning he didn’t shoot Lee as it wasn’t necessary.

Along with John Brown, Edwin Coppock and John Copeland were captured. Barclay Coppock, the youngest of the raiders, was able to escape. He walked for 36 days with a few other escapees until they split in Pennsylvania. He made it back to his mother’s home in Iowa, where he was well protected. However by 1860, Barclay was back in Kansas, fighting for the abolitionist cause. During the Civil War he served for the 4th Kansas Volunteer Infantry. He died when crossing a bridge the Confederates had rigged to collapse.

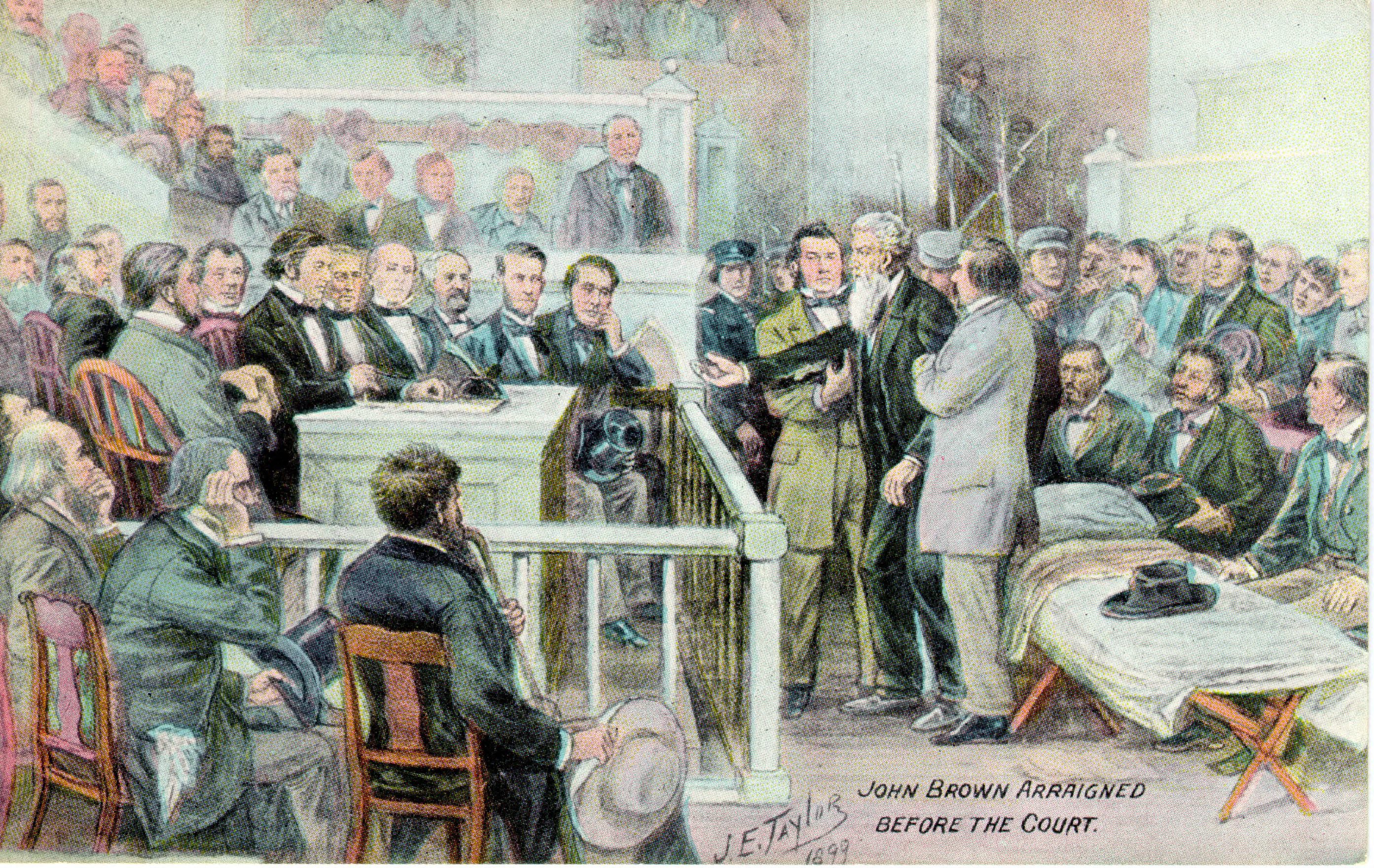

John Brown and his raiders were jailed and tried quickly in Virginia where popular sentiment was turned harshly against them. All of the captured men were sentenced to death, including Coppock, Green, and Copeland.

On December 2, John Brown was executed. It is believed that on his way to the gallows, he asked to stop by Edwin Coppock’s cell. Here he gave Coppock the last spare change he had in his pocket. During the raid, Coppock’s brother Barclay had spent some money on supplies, and Brown hoped to settle a part of that debt before he died.

Although Brown was gone, his men remained in prison awaiting their own sentences. On December 9, John Butler, Edwin Coppock’s adopted father, left from Columbiana County with a petition from many local citizens asking that Coppock not be executed. Butler delivered this petition to the Governor of Virginia, Henry Wise. Wise said that he liked Coppock, but could not do anything without the support of the legislature. Most Virginians were turned violently against John Brown’s raiders- the legislature refused to do anything. Edwin Coppock would die on December 16, 1859.

Before returning to Ohio, Butler was able to spend a few hours with Coppock. Butler wrote in his journal that he was incredibly nervous to meet with Coppock. Once he arrived, Butler was flooded with emotions, thinking back to Coppock’s mother leaving him in Butler’s care and the many years in which Coppock had become family. After over three hours together, Butler wrote that Edwin “Clasped my hand with affectionate attachment Thanking me for My visit but his heart was too full to utter many words, Thus we parted never to Meet again on this side [of] the Grave…”

Coppock’s uncle came to Virginia to retrieve his body, and a well-attended funeral was held in Winona. Eulogies focused on his valiant sacrifice and framed his death as a conflict between Virginia and Ohio, or North and South. Within a few weeks, mourners became angry that Coppock’s body would lay forever in a casket made by Virginians. They exhumed his body, transferred him to a new coffin, and held a new funeral in the county seat of Salem, where a monument stands to Coppock today.

Less is known about the experience of Shields Green while in prison. With his family still enslaved in the South, Green had no relatives to correspond with. He did however, send messages to John Brown in his cell before he was executed. On the day Brown died, Green is said to have sent a message saying, “I am glad that I came and I am unafraid to die.”

While awaiting his fate on the scaffold, John Copeland communicated with his family in Oberlin through eloquent and insightful letters. Copeland did not receive family visitors as Coppock did. Had Copeland’s family attempted to visit him in Virginia, a slave state, they may have been kidnapped and sold into slavery.

Like many of the raiders he was imprisoned with, Copeland believed he had fought for a noble cause, and he was ready to die for it. He wrote on his last day, “And now, dear ones, if it were not for those feelings I have for you-if it were not that I know your hearts will be filled with sorrow at my fate, I could pass from this earth without regret.”

Copeland also wrote kindly of the men who guarded his prison cell, despite the fact that one, Captain John Avis, had fought against him at Harpers Ferry. He told his family that “he has protected us from insult and abuse which cowards would have heaped upon us. He has done as a brave man and gentleman would do.” Copeland asked in one of his final letters, that if his family met these prison guards they should meet them favorably.

Despite the kindness shown by Virginia’s prison guards, Copeland and Green were treated with cruelty by the state after their death. Governor Wise would only release their bodies to a white man. While Coppock’s family and friends were able to hold a funeral for their fallen son in Winona, the bodies of Copeland and Green were sent to Winchester Medical College in Virginia for use by students studying dissection. The residents of Oberlin held a memorial service for all three of their fallen residents that winter, and erected a memorial in their honor.

As John Brown walked to the gallows, he handed the guard escorting him a paper on which he had penned his final message for the nation. The paper read, “I, John Brown am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood. I had as I now think vainly flattered myself that without very much bloodshed it might be done.”

Brown was right. Not long after his death, violent disagreements about slavery plunged the United States headfirst into a Civil War. In fact, Brown’s much publicized execution helped tear the North and South apart. Northerners saw a Southern state that had taken one of their own and unfairly executed him. Southerners saw a band of Northerners unwilling to respect their laws. Both feared that the other would take over the nation.

“The man whom Virginia branded as a Traitor and a Murderer, the people of Salem and vicinity have honored as a PATRIOT and an HONEST MAN. Charlestown gave him a gallows; Salem will build him a monument.” – The Anti-Slavery Bugle; Reinternment of Edwin Coppock; January 7, 1860

On April 10, 1865, exciting news came to Salem, Ohio, the final resting place of Edwin Coppock. The Civil War had ended. The Union had won! People raced into the streets to celebrate, and Dr. J.C. Whinnery climbed into the attic of his offices, where he had stored the original coffin Coppock’s body was sent home in five years earlier. Residents made an effigy of Robert E. Lee (the Confederate general Coppock had once almost shot), and carried him through the streets in the coffin, singing “John Brown’s Body.”

When the Civil War ended, John Brown, John Henri Kagi, Edwin Coppock, Barclay Coppock, Shields Green, John A. Copeland, Dangerfield Newby, and Lewis Sheridan Leary had been gone for five years. But the mark that these Ohio men made on their nation would never diminish.

Interested in learning more? Here are the resources I used to research this blog post!

“Bleeding Kansas.” History.com. A&E Television Networks, October 27, 2009.

Gilot, Jon-Erik. “The Newby Family Fights for Freedom.” Emerging Civil War, February 21, 2019.

Graham, Lorenz. John Browns Raid; a Picture History of the Attack on Harpers Ferry, Virginia. New York: Scholastic Book Services, 1972.

Harvey Elihu Smith, VFM 5997, Ohio History Connection.

Hinton, Richard J. John Brown and His Men: with Some Account of the Roads They Traveled to Reach Harpers Ferry. Funk & Wagnalls Company, 1894.

Howard, Joshua.“Tar Heels at Harper’s Ferry, October 16-18, 1859: Lewis S. Leary.” NCpedia. State Library of North Carolina. 2011.

“John Brown’s Black Raiders.” PBS.

John Brown’s Raid on Harpers Ferry — The Coppoc (Coppock) Cousins / Edwin Coppock / Barclay Coppock.

John Butler Journal, VFM 6246, Ohio History Connection

“John Brown.” Ohio History Central.

“John A. Copeland Jr.” Ohio History Central.

“Lewis S. Leary.” Ohio History Central.

“Shields Green.” Ohio History Central.

Love, Rose Leary. “The Five Brave Negroes with John Brown at Harpers Ferry.” The Negro History Bulletin XXVII, no. 7 (April 1964).

Mendenhall, Thomas C. “The Coffin of Edwin Coppock.” Ohio History Journal.

Webb, Richard Davis. The Life and Letters of Captain John Brown: Who Was Executed at Charlestown, Virginia, Dec. 2, 1859, for an Armed Attack upon American Slavery, with Notices of Some of His Confederates. Smith, Elder, & Co., 1861.