When you approach primary sources in the archives, it can be very helpful to put on your deerstalker cap and think like a detective.

During some regular processing this week, I actually ended up chasing a pair of historic criminals through the OHC Archives/Library.

So come along my dear reader, and I will show you what I have discovered. Then maybe you can do some exciting research of your own!

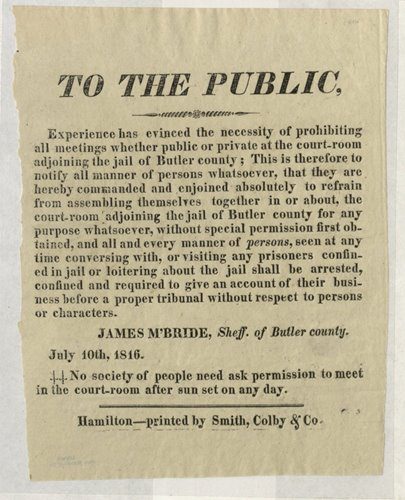

Let me set the scene: recently while adding new collections to our online collections catalog, I came across the document below, and something told me there was more to the story.

What could have happened at the Butler County Jail to cause the sheriff to close the adjoining courtroom?

As anyone who has read Sherlock Holmes will know, one of the man’s most useful talents is his power of observation. While comparing myself to Sherlock Holmes may be a little bit silly, his methods can actually be really useful when answering everyday questions, even in the archives.

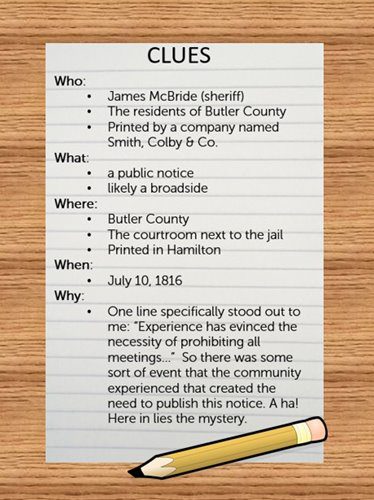

We observe things naturally every day, and our brains process the information quickly. So when it comes to solving a puzzle, it can be helpful to write down each of these simple observations and think through them a little more carefully. Call it a list of clues, if you will.

I like to detail my observations using the always reliable 5 W’s:

With my list of clues prepared, I needed a list of leads to follow (other primary and secondary sources available to me for solving this mystery). Clearly this had something to do with a courtroom and the adjoining jail. Should I check the court records?

By consulting my list of clues, I could see that I would need the Butler County Court records from 1816 or earlier. But I knew that the further back we dive into the past, the less reliable most court records become. It could take a while for this lead to yield even a simple clue.

I got to thinking that an event causing a large public declaration from the sheriff, especially an event dealing so closely with criminals, would surely make the local newspaper. Luckily, the Ohio History Connection Online Collections Catalog makes finding newspapers very simple.

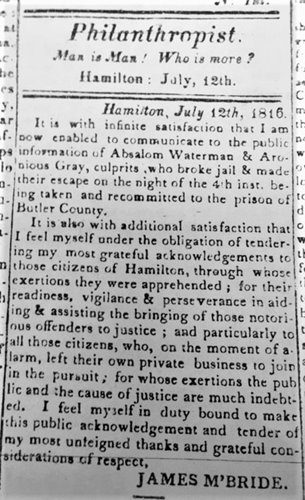

I quickly found that OHC holds a microfilm copy of The Philanthropist, a newspaper published in Hamilton, Ohio, in 1816. I also noticed that this newspaper was published by Smith, Colby, & Co.- the same company that printed Sheriff McBride’s broadside!

Knowing that McBride put out his notice on July 10, 1816, I started there. I found that this exact same notice was printed in The Philanthropist on July 12, 1816! McBride delivered the notice to one printing company, and it was disseminated to the public in multiple places.

Flipping through the rest of the July 12 edition of The Philanthropist, the name “James McBride” caught my attention again.

McBride wrote, “It is with infinite satisfaction that I am now enabled to communicate to the public information of Absalom Waterman & Aronious Gray, culprits who broke jail & made their escape on the night of the 4th inst. being taken and recommitted to the prison of Butler County.”

This must be why McBride wanted citizens to stay away from the jail! Two men had broken out of the Butler County jail on July 4th. After a community manhunt, they were returned. McBride wanted to prevent another prison break.

But the story doesn’t end there, dear reader. As is often the case when it comes to archival research, the answer to one big question sparked many new inquiries.

First: who were the escaped prisoners? McBride’s thank you to the community on July 12 noted that the prisoners had escaped on July 4. So I flipped backwards through The Philanthropist until I came to July 5, 1816. Here McBride had submitted a notice of a $50 reward (or $25 each) for the capture of the two “villians.”

Accompanying this notice were clear descriptions of each man’s appearance.

Absalom Watterman: “apparently about 24 years old, nearly 5 feet 6 inches high, light, fair complexion, stoop shouldered, thick set, and head inclining forwards, wore a dark colored coat & grey pantaloons.

Arronius Gray: “about 22 or 23 years old, five feet ten or eleven inches high, black hair & beard, dark complexion & dark eyes, he wore a light jacket with black spots, dark pantaloons & blue coat.”

Unfortunately this is all I would learn about our two escaped prisoners, as my hunch was correct, and there are no reliable court records covering their time in the Butler County penal system. (Atleast not that I could find at the OHC Archives/Library. A local Butler County archive may be more adept at following this specific lead.)

But I had another question to follow: what exactly did this “courtroom adjoining the jail” look like? Was the jail attached to the larger county courthouse? Was it really that easy to walk in and talk to a prisoner?

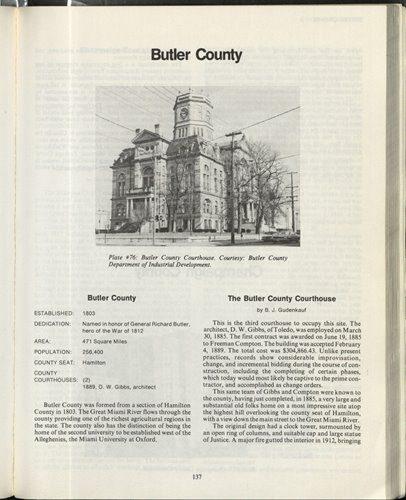

To try to answer these questions, I consulted a few directories of historic county courthouses. Unfortunately, these directories only reported on a courthouse built for Butler County in the 1880s.

From The Development of Ohio’s Counties and Their Historic Courthouses, published by the County Commissioners Association of Ohio

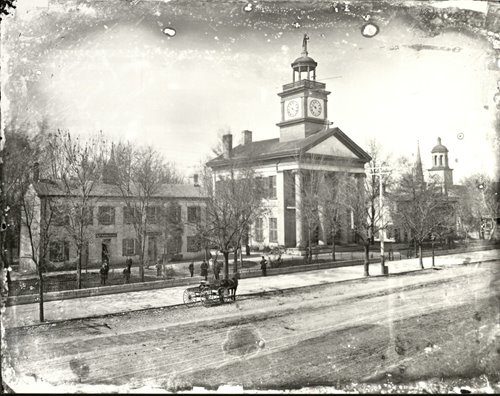

I did find one exterior image of an earlier courthouse in OHC’s collections (OVS 3392).

Feeling frustrated and without an easy answer, I consulted OHC’s section of county histories, specifically Butler.

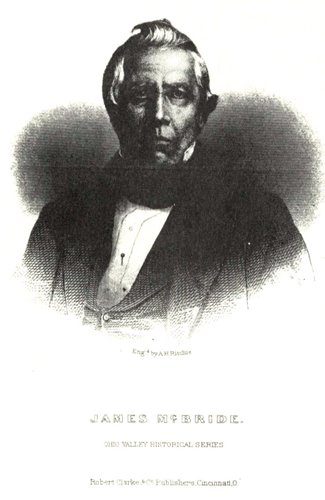

While I learned very little about the courthouse, these sources ended up teaching me a lot about the source of this material- James McBride. McBride was born in 1788 in Pennsylvania, and he came to Butler County, Ohio at the age of 18, during the county’s infancy. He became a noted local historian whose books are still held in many libraries, including at OHC. McBride boasted a long list of accomplishments including serving as Mayor of Hamilton, Ohio. He died in 1859, ten days after his wife.

As I followed each lead and filled out my list of clues, each bit of new information led me to many more questions and insights.

For example, I started to wonder about the escaped prisoners’ clothing. Were prisoners not wearing striped jumpsuits yet in 1816? Each escaped man was described as wearing a different outfit, made of what seemed to be their own clothing. And what exactly was a “light jacket with black spots?” Were polka dots fashionable in 1816? Or was his jacket dirty?

Furthermore, I wanted to know what this says about the values of the city of Hamilton in 1816. It seems like residents of the city were quick to catch the two criminals. Were they not able to disguise themselves or travel quickly? Was this town “tough on crime?”

While I don’t have the answers to these questions, it is exactly these curiosities that keep people coming back to the archives and lead to great new works by modern historians. Acting as detectives of the past, historians can find answers to the most pressing questions and help the people of the past inform our future.

We can all be detectives of the past if we allow primary sources to lead us to a new conclusion. Have you ever researched your family’s genealogy? Or looked through old photographs and scrapbooks in your parents’ basement? You may already be a detective of your own past!

All you need is a notebook, a pencil, and a local library or archive to start your adventure and become your own Sherlock Holmes!