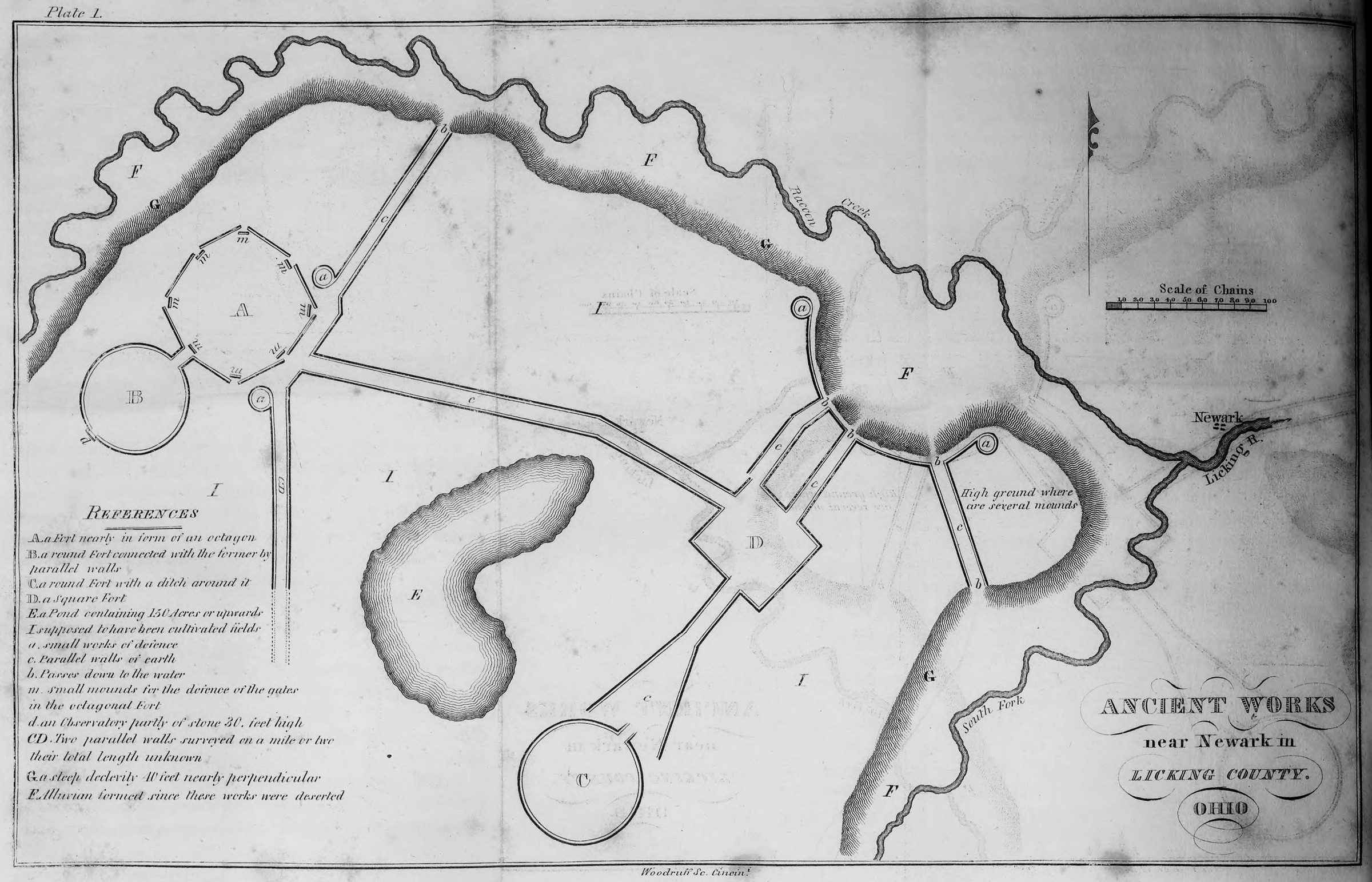

1820

This is the earliest known map of the Newark Earthworks. Mapped by Caleb Atwater, this depiction was published in Description of Antiquities Discovered in the State of Ohio and Other Western States (1820).

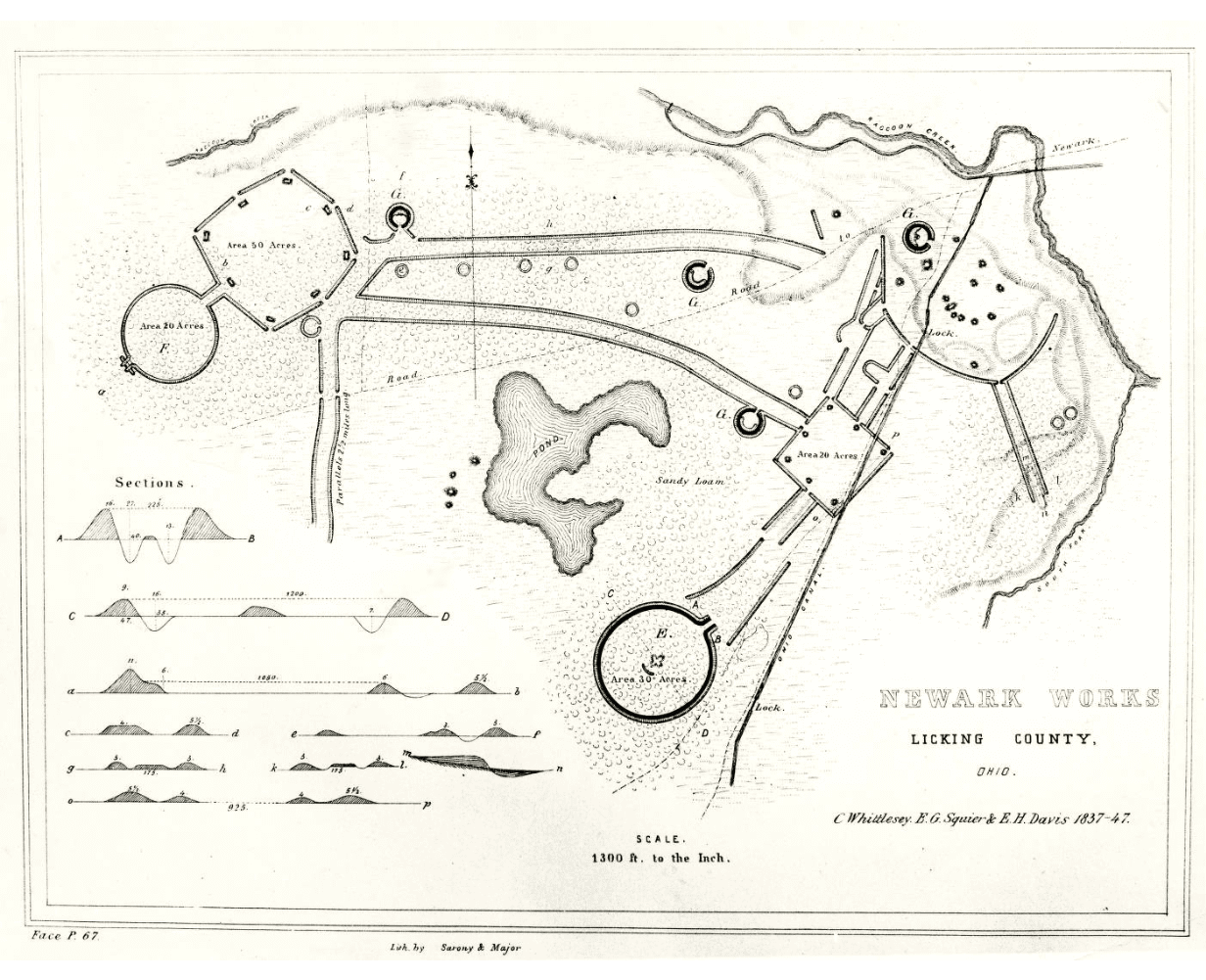

1848

Produced between 1837-1847, Squier and Davis published this map of the Newark Earthworks in Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley (1848). Note the construction of the Ohio and Erie Canal, established in 1825, which intersects multiple earthen embankments at the eastern extent of the earthwork and a road (now West Main Street) which bisects segments of the earthen wall structure.

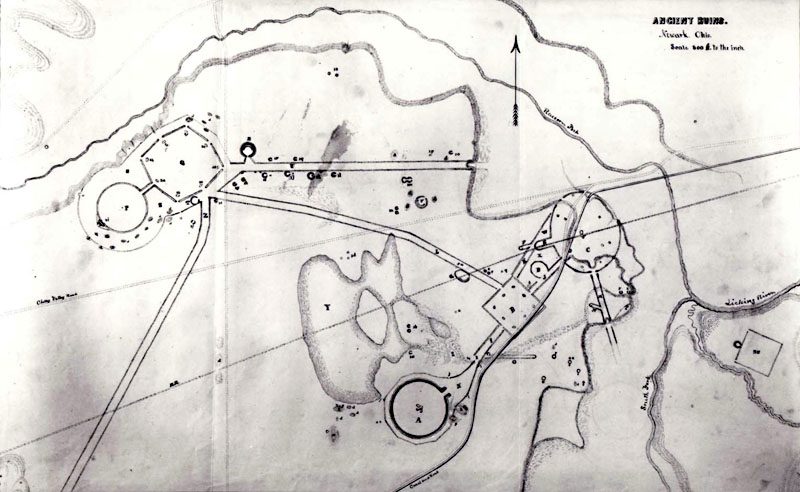

1862

Image courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society

Newark natives, James and Charles Salisbury published this map in Accurate Surveys and Descriptions of the Ancient Earthworks at Newark, Ohio (1862). The Central Ohio Railroad had been established just years earlier in 1857, and is seen bisecting the pond just north of the Great Circle and again impacting many of the eastern earthen embankment structures.

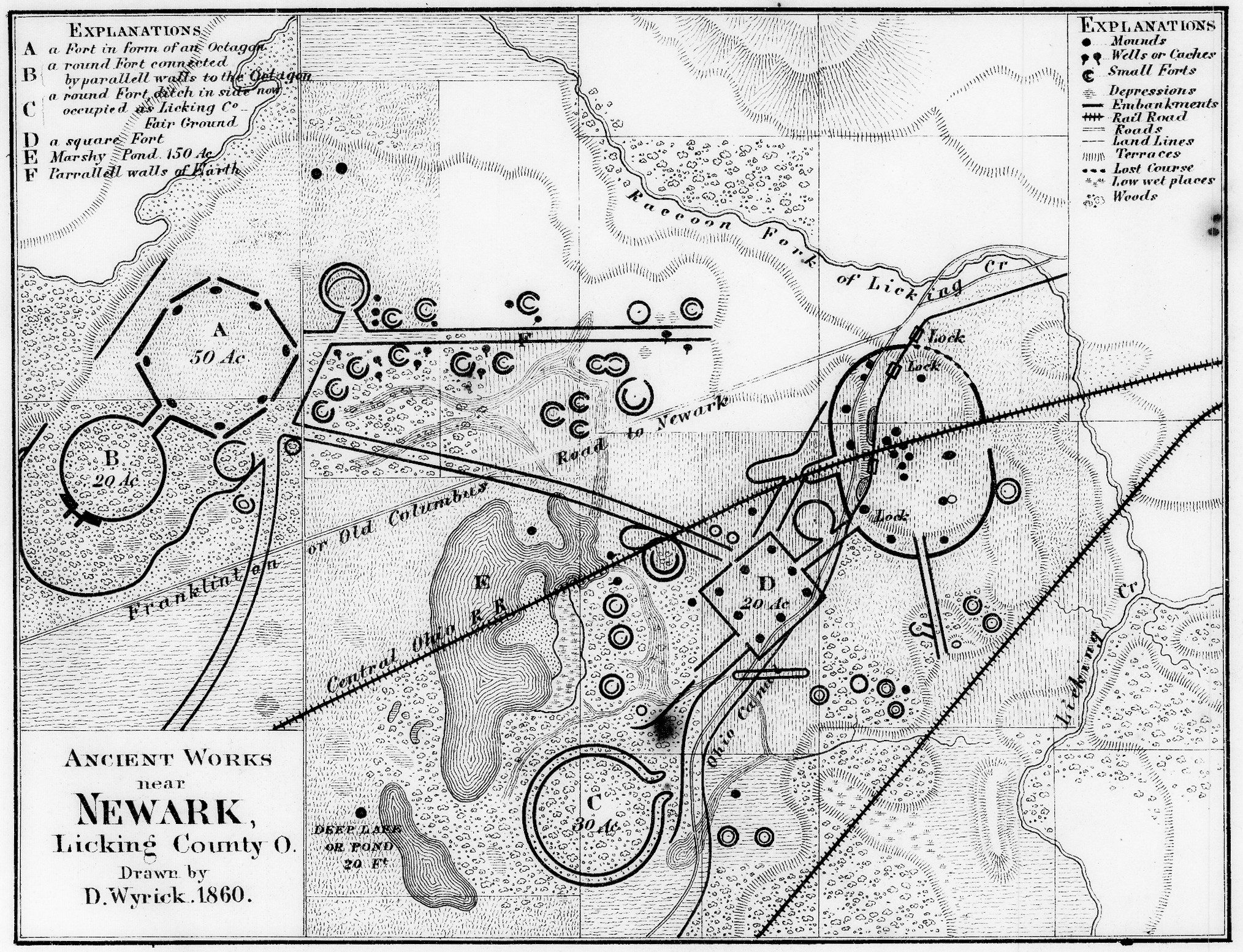

1866

David Wyrick's 1860 map published in Beer's Atlas of Licking County (1866). The same David Wyrick associated with the Newark Holy Stones high jinks. Modern infrastructure is most clearly visible within this map, including roadways, the Ohio and Erie Canal and the Central Ohio Railroad line. Eagle-eyed readers may also note an additional, unnamed, railroad has appeared on the eastern periphery of the earthwork complex. At the time, this was the proposed route of the Hocking Valley Railroad. Also note item 'C' on the map key, which denotes the Great Circle as home to the Licking County Fairground. Read more about the Great Circle's use as the Fairground here.

While looking at the maps above, it is difficult to imagine the earthworks as anything but a singular complex, only sometimes impacted by lines of transportation.

However, this section of the Newark Township Plat Map, published in Beer's Atlas of Licking County (1866), represents the Newark Earthworks only as three separate 'Ancient Forts'. The landscape is otherwise overwhelmed by privately owned parcels and dotted with homes. In 1867, the Licking County Pioneer, Historical and Antiquarian Society was created with the intent to prevent further destruction of the earthworks, focusing on the Great Circle and the Octagon. Between 1892 and the early 1900s, the Octagon Earthworks was home to the Ohio National Guard, a move believed to have been an act of preservation at the time.