I am used to thinking of Ohio’s Hopewell culture (circa 100 B.C. – A.D. 400) as the time when a far flung interaction sphere brought enormous quantities of exotic raw materials and artifacts into Ohio. It’s becoming increasingly clear, however, that virtually all ancient American Indian societies valued rare and beautiful things and did their best to acquire them. In my book Ohio Archaeology: an illustrated chronicle of Ohio’s ancient American Indian cultures, I wrote that there was “little evidence for trade during the Late Prehistoric period” (circa A.D. 1000 – 1650). I argued that increasing intergroup conflict largely had eliminated the need for these kinds of social symbols and created an environment in which long distance travel and trade would have been too risky to undertake — at least on a regular basis. I was wrong.  Ohio’s Madisonville site, a major Late Prehistoric village and cemetery now encompassed by suburban Cincinnati, was an important center of interregional trade. In my July column in the Columbus Dispatch I point out that a number of artifacts that originated in Europe found their way to Madisonville long before any Europeans had set foot here. Those artifacts certainly are the most spectacular evidence of trade during this period, but they are far from the whole story. Also found at Madisonville are grooved stone mauls and bone rasps from the upper Mississippi valley, pipes from southern Wisconsin, a ceramic head-effigy pot from Missouri, and engraved shell gorgets from eastern Tennessee. Clearly, trade was an important activity during the Late Prehistoric period and the rare commodities obtained through these extensive networks must have been important status symbols.

Ohio’s Madisonville site, a major Late Prehistoric village and cemetery now encompassed by suburban Cincinnati, was an important center of interregional trade. In my July column in the Columbus Dispatch I point out that a number of artifacts that originated in Europe found their way to Madisonville long before any Europeans had set foot here. Those artifacts certainly are the most spectacular evidence of trade during this period, but they are far from the whole story. Also found at Madisonville are grooved stone mauls and bone rasps from the upper Mississippi valley, pipes from southern Wisconsin, a ceramic head-effigy pot from Missouri, and engraved shell gorgets from eastern Tennessee. Clearly, trade was an important activity during the Late Prehistoric period and the rare commodities obtained through these extensive networks must have been important status symbols.

The evidence for warfare during this period also is clear, however, so this interaction may have taken place in the periods between intermittent eruptions of violence — possibly in the context of neighboring groups negotiating alliances with one another. This is very different from what was happening in the Hopewell era for which there is virtually no evidence of intergroup violence of any kind and the flow of exotic materials into Ohio was orders of magnitude beyond anything seen either before or after. Trade almost surely was a part of what was going on, but the sheer volume of hyper-exotic material accumulating at Ohio earthwork centers and the lack of almost anything from Ohio showing up at the other ends of the interaction sphere suggest to me that the monumental Hopewellian earthworks were pilgrimage centers. Madisonville, on the other hand, was something much more down-to-earth and familiar. It was a large village and a center of trade and commerce for many generations of Late Prehistoric folks.

In fact, I would argue that what we see at Madisonvilleis exactly what more or less ordinary trade should look like in the archaeological record. The accumulation of prodigious amounts of precious materials at Hopewell earthworks may not represent the offerings of pilgrims, but it’s something more than trade. For more information about the Madisonville site, I recommend Penelope Ballard Drucker’s marvelous book The View From Madisonville: prehistoric western Fort Ancient interaction patterns. If you want to read more about my ideas on Hopewell pilgrimage, the best place to start is my chapter in Recreating Hopewell, edited by Doug Charles and Jane Buikstra: “The

Great Hopewell Road and the role of the pilgrimage in the Hopewell Interaction sphere.” You also can check out the following related blog posts: The Newark Earthworks: a place of pilgrimage The Fort Ancient Earthworks — place of pilgrimage Ancient American pilgrimage: communitas or costly signaling?

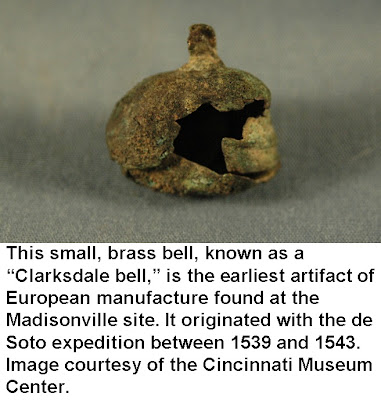

Special thanks to Bob Genheimer, George Rieveschl Curator of Archaeology at the Cincinnati Museum Center, for taking the time from a busy field season to take the picture of the Clarkdale Bell.

Brad Lepper