On the evening of February 27, 1874, Sarah Knowles Bolton addressed a large group of women who had just that day conducted their very first ‘saloon raid.’

She reported that “only twice before in her life had she felt as weak as on this occasion. Once was when she had joined the church; the other was on the night of her marriage.[1]”

Bolton and the women she addressed were at the forefront of a new movement that came to be known as the Women’s Crusade. Crusaders were banding together to approach saloon keepers with prayer and a request to cease the sale of alcohol.

When it came to the Women’s Crusade of 1873 and 1874, all eyes were on Ohio. Some of the most well-documented crusades occurred in Southern Ohio cities like Hillsboro (see below) and Washington Court House.[2]

As morning arrived in Berea on the final Friday of February 1874, many of the township’s women were busy organizing, writing a constitution, and cementing a local women’s league. Among its first leaders were Mrs. Dr. Godman (President), Mrs. C.U. Pond (First Vice President), Mrs. T.K. Dissette (Second Vice President), and Mrs. Dr. Allen (Secretary).

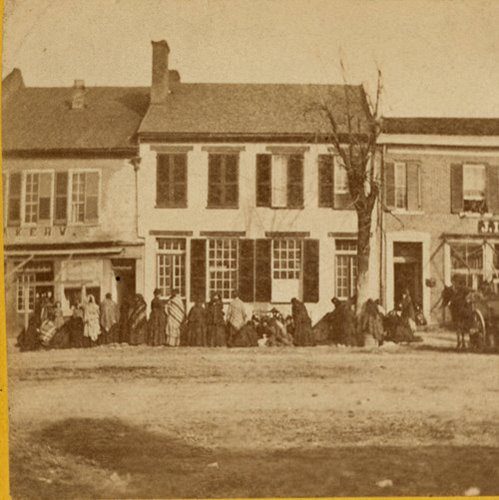

With their leaders chosen, the approximately fifty women formed two orderly lines and steadfastly marched out the doors of the Congregational Church. As the Cleveland Leader reported, “People upon the street seeing the ladies come from the church knew at once that the time had come for invading the saloons.[3]”

The first stop on their crusade was the saloon owned by Thomas Chope. Chope, a butcher by trade, ran a flour and feed store as his main form of profit. His saloon was attached to the back of the store, almost as an afterthought.

When the women entered his store, Chope attempted to hide the attached bar by locking the door between the store and the saloon. Meanwhile, many of the male customers attempted to escape through the windows. Eventually, Chope unlocked the door and the women knelt in his saloon and began to pray.[4]

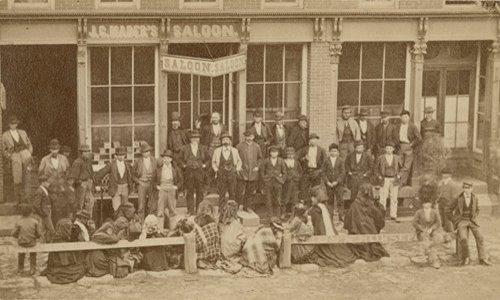

The women visited about four saloons that day, conducting a “pray-in” at each. After praying, the leaders of the crusade would ask the saloon owner to sign a pledge promising to stop their sale of alcohol. While most saloon owners were kind to the women, few were willing to give up their business.[5]

Only one saloon keeper, Martin Cummins, refused to even open his doors. He was drinking at Thomas Chope’s saloon when the women first arrived. Fearing that he would be next on the list, he ran home and locked up his doors. Unwavering, the crusaders knelt on his front porch and prayed.[6]

Women led many early temperance crusades, because they had the most to lose from the continued sale of liquor. Many women faced physical abuse from intoxicated male drinkers, and countless wives struggled in poverty due to the spending of alcoholic husbands.

Women demanded temperance through a crusade of nonviolent “pray-ins,” because they had no other way to be heard. In 1874, women in the United States could not vote. Without a voice in regular political discussions, women had to force their way into the conversation.

Bucyrus, Ohio.

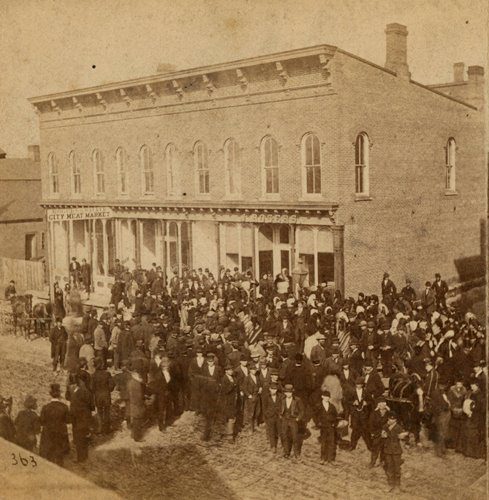

The Women’s Crusade continued locally across Ohio throughout 1874. Unfortunately, not all protests remained as nonviolent as those in Berea. Sarah Knowles Bolton summarized a few harrowing events in her autobiography:

“In one town, a man who bore an unfortunate reputation, had a gun shop in one half of his saloon. When the women entered, the guns were fired, and the room soon filled with smoke, so that it was difficult to breathe, but the services were held. The next day when we came, the saloon keeper…gave up his business and became a changed man.[7]”

Many crusades caused public crowds like this one in Mount Vernon, Ohio.

“On the third day in Cleveland, on the West side, a mob, headed by an organization of brewers, rushed upon the Crusaders who were kneeling on the sidewalk, the saloon having been closed against them, kicked them, struck them with their fists, and hit them with brick bats. Mr. Doolittle who attempted to defend the women was so badly injured that for two years or more he was confined to his bed.[8]”

In the fall of 1874, after about a year of local Women’s Crusades, women came together in Cleveland, Ohio, to have a convention and officially form the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. This national association of women built an infrastructure that would aid in the organizing necessary to petition for the right to vote. The Women’s Christian Temperance Union would stand up for many women’s issues in the years to come, and it is still active today.[9]

Women’s Christian Temperance Union Seattle Headquarters, 1914.

As that first day of protest came to a close, the women of Berea gathered to hear Bolton’s address and decided that the following day the crusaders would “move on their strongest foes- the saloon keepers at the depot, just outside of the corporation limits.[10]” There was no time to rest, for there was work to be done and these women were ready to do it.