The First Year – First Hand from the Archives by guest blogger Erin Claussen

In January of 1938, the Lithic Laboratory for the Eastern United States was founded at the Ohio Archaeological and Historical Society, now the Ohio Historical Society. An article in Museum Echoes, the Society’s newsletter, of the same month proclaimed its purpose: to study the lithic materials (stone, flint, etc.) pertinent to the material culture of the American aborigines, and of methods and techniques employed in their utilization. The article went on to explain that the reason for embarking on this initiative was simply that such a study had been sadly neglected by the field of archaeology prior and that finally undertaking it would help throw light on the origin, relationships, migrations and trade routes of the first Americans. An understanding of these methods and techniques and thereby the peoples that employed them was to be achieved by experimentation with flintknapping. While the basics of stone artifact production were known at the time, the more refined techniques continue to defy present-day skill.

The first year-and-a-half of work by the Laboratory was funded entirely by the contribution of two Ohio Archaeological and Historical Society officers, then President Arthur C. Johnson (whose career in newspapers culminated with his being editor in chief and associate publisher of the Columbus Dispatch) and Board of Trustees member H. Preston Wolfe (an entrepreneur and Columbus Dispatch publisher who was also a champion for the economic and civic welfare of Columbus). Their combined endowment provided an operating budget of $2000 for 1938 — about $33,000 2013 dollars, which even adjusted might still be considered a meager amount given the work that was to be done, but that nevertheless seemed to prove adequate in making strides towards the goals of the Laboratory.

H. Holmes Ellis, a recent graduate of the University of Michigan’s Anthropology Department, was hired by the Laboratory shortly after its founding as a research associate to oversee much of the work carried out. His masters thesis for the Ohio State University entitled Flint Working Techniques of the American Indians: An Experimental Study prepared in 1939 and published by the Ohio Historical Society in 1957, was one of the few, but certainly the most important, of the formal publications resulting from the pioneering foray into the nascent sub-field of Experimental Archaeology. Recent efforts to catalog the Ohio Historical Society’s Archaeology Department correspondence files along with some additional documentary research have shed more light on what the efforts of the Lithic Laboratory entailed.

Letters from the first half of 1938 to and from Richard G. Morgan, the Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society’s Curator of Archaeology, reveal that the first order of business for the Lithic Laboratory was visiting and collecting specimens from prehistoric quarry sites, workshops and flint disc caches throughout the Midwest with the eventual goal of creating a comprehensive series of comparative materials from the entire eastern United States.

Helping with the process of identifying sites and securing specimens in Indiana was Glenn A. Black. Black, who had trained at the Ohio Archaeological and Historical Society earlier in his career, had gone on to become a pioneer in the study of Indiana prehistory. He was affiliated with both the Indiana Historical Society and Indiana University (where the archaeology research center now bears his name). In a letter dated the 18th of April 1938 to Morgan, he details an excursion:

I made a trip to Harrison County after flint the other day and returned with several fine nodules. Some of them were exposed to the air while others were taken from the damp earth. Those that had never been dry are now buried in the ground here to keep them moist until such time as they are needed. I thought that I had seen big workshops before but nothing to what I saw last week. The county is lousy with them. The nodules are very accessible due to the fact that they erode out of the banks of small streams during high water. Wherever they occur in the stream bed there is a workshop on the bank.

Either while this preliminary regional fieldwork was taking place, or perhaps one year earlier, H. C. Shetrone, then the Director of the Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society, embarked on a research trip in the name of the Laboratory much farther afield.

Though the date of the article and the publication from which it came has been lost to time, a newspaper clipping most likely from early 1937 or 1938 describes the founding of the Lithic Laboratory and details a planned trip by Shetrone to England: Brandon, England, the only place where the art of flint chipping is still practiced after 600 years, will be Dr. Shetrones destination when he sails from New York, June 2. Here he will live with the so-call flint-knappers and make a close study of their methods and techniques.

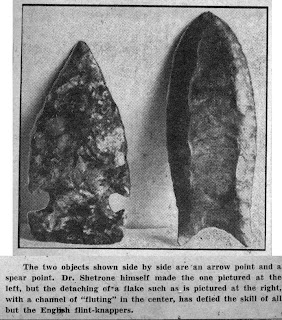

The article mentions that the Laboratory would be set up subsequent to the trip. A photo accompanying the piece depicts two projectile points one of which having been fashioned by Shetrone himself. Hands-on involvement in executing the mission of the Laboratory extended to the top of the Society’s organizational hierarchy.

By October, sufficient fieldwork had been carried out, raw material had been collected, existing literature had been reviewed and experimentation had begun, as detailed in the Museum Echoes of that month. As led by Ellis this included determining how the flint was quarried and roughly shaped or reduced, replication of cruder tools by means of direct percussion (the use of stone, bone or wood to strike flakes) and trials involving indirect percussion (the application of force to a pointed tool to strike flakes) were underway. Up next was to be experimentation with pressure flaking (as the name suggests, the application simply of pressure not of striking force to remove flakes), which was believed to be the method responsible for some of the most refined lithics.

Other correspondence from the Laboratory’s inaugural year indicates that it enjoyed the support and enthusiasm of the archaeological community broadly. I hear great things about your Lithic Laboratory, proclaimed Thorne Deuel of the Illinois State Museum in a letter to Morgan in June. The April letter from T.M.N Lewis of the Tennessee Valley Authority discussed in Part I: The Lithic Laboratory in Time in which Lewis requested information about the classification scheme for lithic artifacts to be employed by the Laboratory, suggests that it was regarded as something of an authority on its namesake subject. A December letter to Morgan from the Alabama Museum of Natural History also highlighted that knowledge of the sort that the Laboratory sought to generate was sorely needed in the wake of massive New Deal-sponsored archaeological undertakings:

As you probably know, our Museum has been sponsoring a WPA statewide archaeological survey for the past several years. We are operating six field crews in North Alabama, and a central laboratory in Birmingham. All material excavated in the field is brought in to the laboratory for cleaning cataloging, restoration and study. We have good supervision for all of the various departments except studies of flint and stone material.

We are very anxious to add a specialist in the field of flint and stone to our present staff a person with archaeological background and knowledge of material. Since you are in charge of the lithological laboratory there, we thought you could recommend someone to us.

Collaboration and knowledge-sharing was indeed intended to be a central tenant of the Laboratory. The aforementioned January 1938 Museum Echoes, the newsletter of the Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society, in which the Laboratory was introduced to readers spelled this out:

During the past few years similar projects have been set up in one or another of the larger museums of the country for the study of materials utilized by the Indians, the so-called Moundbuilders, and others of our native American peoples. These much-needed projects have freely served the needs of the Ohio State Museum, as well as their own, in the spirit of cooperation so characteristic of the museum world at the present time. The scope of the Lithic Laboratory for the Eastern United States, as its name indicates, is in keeping with this modern policy. In addition to serving our own immediate needs, we shall share the services of the Laboratory with others.

At the close of 1938, the Lithic Laboratory had already gained renown in the small but growing field of professional archaeology and was on its way to achieving goals set forth. The next few years would see a continuation of efforts including the acquisition of a tangible part of the Laboratory’s legacy that survives in the Ohio Historical Society’s collections.

Editor’s Note: The images from the newspaper article shown here are from the scrapbook of the late Robert C. Goslin, a former assistant in Archaeology and Natural History at the Ohio Historical Society. The year and source of the article are not noted in the scrapbook.