Welcome to Our Summer Interns!

Meet Grayson and Grace—two of our outstanding summer interns at the Ohio History Connection!

Emily George was on a mission. She had heard about the Williams mastodon while growing up, and about how her grandfather Gus George had helped excavate the skeleton in Columbus in the mid-1950s. After talking with her family about the mastodon for a school genealogy project in 2008, she thought “I wonder where that skeleton is today!?” But where do you go to look for a mastodon!? The internet provided no leads about the Williams specimen. You can find all kinds of information about other Ohio mastodons that have been associated with the Ohio History Connection: the Orleton mastodon found in Madison Co. in 1949, the Conway mastodon found near the Clark – Champaign county line in 1887, and maybe Ohio’s most famous mastodon the Burning Tree mastodon from Licking Co. excavated in 1989 by the Ohio History Connection’s own Brad Lepper. But where was the Williams mastodon? Emily was determined to find out.

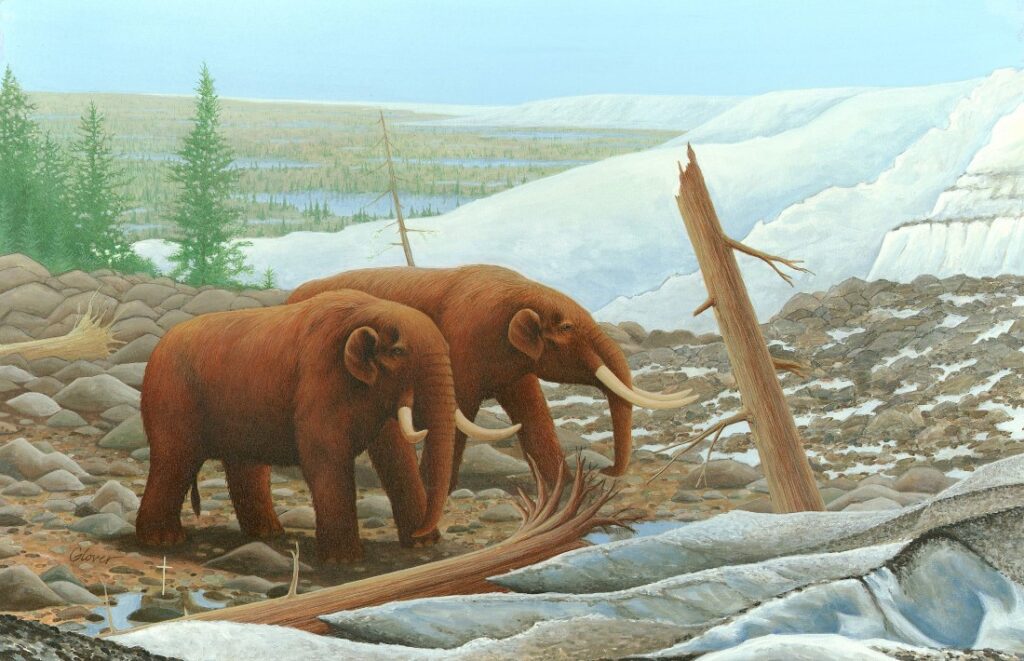

Mastodons at the edge of the glacier in Ohio (illustration by Jim Glover, ODNR)

Mastodons were large elephant-like mammals that roamed Ohio near the end of the Pleistocene Epoch, or Ice Age, which ended about 11,700 years ago. The American Mastodon, a uniquely North American species, lived in Ohio with their more well-known but very distant cousins, the mammoths. The mastodon may not be as well-known, but there are more mastodon finds in Ohio than mammoth finds – by about 3:1. Most finds are individual teeth or maybe a few bones but occasionally a more complete skeleton is unearthed. The Conway Mastodon at the Ohio Historical Center is one of the most complete skeletons known from the state. It was discovered in 1887 near the border of Clark and Champaign counties.

The Conway mastodon at the Ohio History Center (Ohio History Connection photo).

So back to our story. Gus Gorge was the son of Greek immigrants and was born and raised in Youngstown, Ohio. He moved to Central Ohio with his wife in the early 1950s. He worked at Beulah Park for many years and later ran his own construction business. He was described by Emily as “the hardest working, kindest, and most generous person I’ve ever known”. Gus got involved with the excavation of the mastodon skeleton in 1954 when he was digging a foundation for the house of a Mr. Harry Williams. They came across bones while digging and one of his employees assumed that they were cow bones. Gus having knowledge of horses and other livestock could tell they were something very different. The house on Harrisburg Pike is now gone, having been replaced by a car wash in 1987.

To find the Williams specimen, Emily tried contacting several museums and universities, including the OSU Museum of Biological Diversity, the Department of Archaeology at OSU, and the Ohio Archaeological Society, University of Akron, Kent State University, University of Cincinnati, and even The Smithsonian. But no one had any record of a mastodon being uncovered near Green Lawn Cemetery in the 1950’s. After 15 years of searching, she was getting frustrated. In Emily’s first email to me, in late June of 2020, she said “I am writing to you because locating the skeleton has not been very easy”. The Williams mastodon sounded very familiar to me, and a quick check of our records showed that we did indeed have the skeleton! I was pleased to be able to write back that we not only had the bones, but as an added bonus we had about a dozen color slides of the excavation in our files. Sure enough, Emily and her father Louie were later able to identify Gus hard at work in the photos!

Gus George (lower right, facing camera) at the excavation site, 1954 (Ohio History Connection photo).

After all these years of searching and waiting Emily and her family were very excited to come and see the skeleton. However we were right in the middle of the covid pandemic, and pre-vaccine. The museum was closed and we weren’t able to have visitors in the collections. So the George family patiently waited, and waited some more. We stayed in touch over the next year, and finally on November 1, 2021 the George family made the sojourn to our Collections Facility and were able to see the skeleton they heard so much about – 67 years after it was excavated.

Emily George (center), holding a large molar from the Williams mastodon, surrounded by her family. From left to right, Kevin Schollenberger, Claire George, Emily, Missy George, Louie George (Ohio History Connection photo).

Though the Williams mastodon has been in the ownership of the Ohio History Connection since it was first uncovered, it was considered “lost” by some. This is because when we moved from the old museum building on the OSU campus in 1970 to the then new building at its current site on 17th Ave., many of the natural history collections remained at OSU for teaching and continuing research projects. Then in 2014 we moved some of these specimens from the storerooms of the OSU Museum of Biological Diversity to our collections facility. This included the Williams mastodon skeleton, which fit in seven large storage boxes.

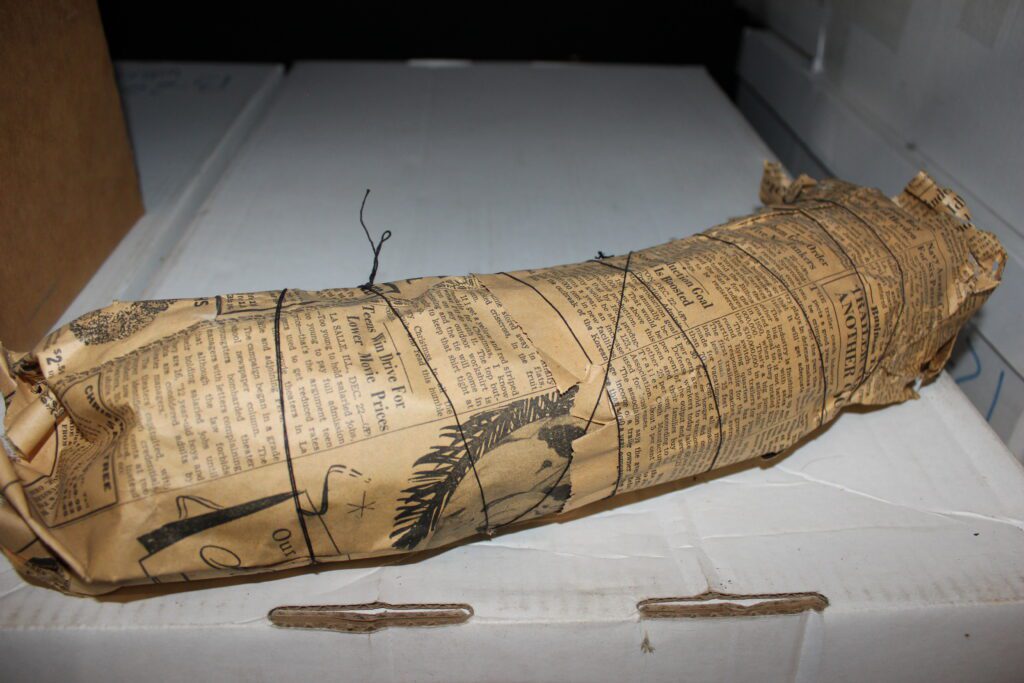

The bones from the Williams mastodon are fragmented as is often the case with Pleistocene remains from Ohio. However the teeth are well-preserved, some still sitting in their bony sockets, and large pieces of the tusks are present. Some of the tusk sections are still wrapped in the original 1950’s newspaper and string that was used right after the excavation to help hold the fragile tusk material together.

A molar and tusk section from the Williams mastodon (Ohio History Connection photos).

Stories like this show that museums are doing their job, which in part is to preserve valuable specimens, artifacts, and objects in perpetuity. Research is important in all disciplines, and one of the keys to research is in the name itself. To “re-search” is to search again. This means that once research is published it can then be verified by other scientists, by checking and replicating the results – by re-searching. In the case of the Williams mastodon specimen, it can be used by scientists as one piece of the puzzle to help answer any number of questions, ranging from species extinction, to climate change, to the flora and fauna of Ice Age Ohio.