For several years our volunteers in the natural history collections at the Ohio Historical Society have working on cataloging a backlog of butterflies and moths. It is a slow, delicate and tedious project, which would never get accomplished without the help of our volunteers.

When we first started a computerized catalog of collections during the late 1970s and early 1980s, memory space on main frame computers were much more limited than even the simplest desktop or laptop computer today. As a result, we decided to only catalog two or three representative of each species, leaving the others uncataloged in groups of insect cabinets and drawers. As computer memory has expanded we now are trying to catalog everything so that a researcher or an exhibit planner can see via computer the entire spectrum of our collection. This is valuable especially for researchers, who might want to compare many specimens for color variation, size variation, etc. In the insect world especially, it is still possible to discover by close examination of a collection that what we originally thought were specimens of a single species are actually two closely related species perhaps one even being a species new to science! That dream, plus better collection management in general, drives us to get everything in our collections in both a hard catalog and a computer database catalog. You can view that computerized catalog online here.

Recently, our volunteers were cataloging about a dozen drawers full of moths in the family Sphingidae. Members of this family are generally known as sphinx moths or hawk moths, while their larvae are often known as hornworms (AKA the Tomato Hornworm which many people are familiar with when they eat the leaves of our tomato plants).

Some of the hawk moths are among our faster flying insects able to reach speeds up to 30 miles per hour. [As a dragonfly fan, I have to add that large dragonflies have clocked accurately up to 35 miles per hour but even 30 mph is really fast for an insect.] World-wide there are 1,200 known species of Sphingidae, with the largest numbers in the tropics. In North America there are 123 species, with 43 known from Ohio.

One of the species I enjoy the most is the Clearwing, or Hummingbird Moth, Hemaris thysbe. These yellow, red and black moths are about just less than two inches long. Most of their wings are clear of the scales typical of most Lepidoptera, and therefore partially transparent. They hover near flowers with fast moving wings that almost disappear due to the speed and transparency making them look very much like a hummingbird. Unlike a hummingbird, instead of a long beak, they have a long coiled proboscis (think elephant trunk or tongue) that they uncoil to reach out and sip nectar. Many people see them and think at first they are a hummingbird. They are cool!

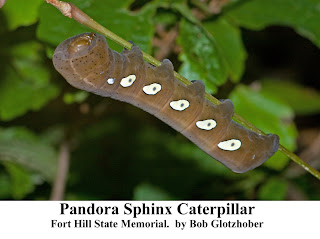

Beauty is in the eye of the beholder but a lot of sphinx moths and even their caterpillars are quite spectacular to those of us who are not “bugged” by insects. Perhaps the most beautiful of all the Sphingidae is the Pandora Sphinx, Eumorpha pandorus, the photo of this adult taken in Missouri. Even the Pandora caterpillar is bold and colorful, as shown in this image from Fort Hill State Memorial in Highland County, Ohio.

The Pandora Sphinx caterpillar can grow to 3.5 inches long, and may be cinnamon (like this one), green, orange or pink. They feed on the leaves of Virginia Creeper, grapes and related plants. But wait! I titled this blog Halloween Sphinx Moths and I have not said anything at all scary or in any way related to Halloween. Oops. You did not notice that the title also said “Part I”. Watch for my next blog, coming out in time for Halloween!

Bob Glotzhober, Senior Curator, Natural History