Hi there! I’m Lily Birkhimer, the digital projects coordinator here at the Ohio History Connection—and a proud member of the team that put together the pilot project you can come and explore in Gallery 2. I was drafted to the team to help connect the museum objects on display with our vast collection of archival holdings, which include visual materials, manuscripts, newspapers, books and more. Although I’m part of the Outreach Division within the organization, I work closely with our collections of all types when digitizing materials for exhibits, in response to reproduction requests and to share on our digital collections website, Ohio Memory.

Because I don’t usually interact with our museum collections in my everyday work, this project was a great opportunity for me to learn more about the fascinating items we hold and the stories behind them. Among the many types of decorative arts featured throughout the gallery, I was particularly drawn to the series of celebrity flasks that we chose to highlight in the glass cases, which date back to the early 19th century. These early “pop culture” items feature well-known cultural icons and politicians of the time, like Lord Byron, Benjamin Franklin and George Washington, as well as more generic figures like Columbia, the female personification of the United States.

One piece that immediately jumped out at me was the flask featuring Jenny Lind, the “Swedish Nightingale.”

I first learned about Lind, a Swedish opera singer popular during the mid-1800s, while working on Ohio Memory. We have a similar glass bottle produced by Ravenna Glass Works included on Ohio Memory courtesy of the Reed Memorial Library, who holds the original in their Portage County Glass Collection. You can also see a 1951 window display from Lazarus in downtown Columbus, celebrating the centennial of a performance Lind gave in the city in November 1851, as well as passers-by admiring the detailed diorama.

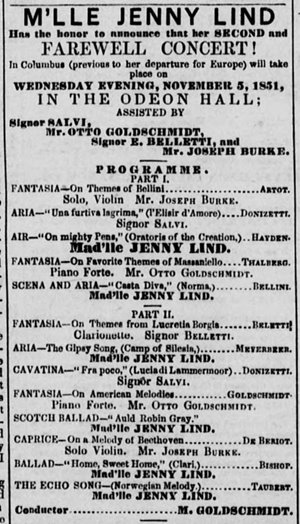

Jenny Lind was also documented in a number of newspapers that are available in digital format on Ohio Memory, appearing in a gossip column speculating about her marriage and in a review of her 1851 concert in the capital city. You can even see a full program for her farewell concert at Columbus’s Odeon Hall.

Using the fantastic historical resources we have available to trace the connections between the objects in our collections and Ohio’s many stories is one of my favorite parts of working on this project and at the Ohio History Connection. We hope you’ll make a visit to see the over 1,000 unique pieces in Gallery 2 and to see what connections you might find!

– Lily Birkhimer, Digital Projects Coordinator