In the year 455, a Germanic tribe known as the Vandals sacked Rome. For fourteen days the Vandals plundered the city, looting great amounts of treasures, destroying objects of cultural significance, and then shipping many captured citizens to North Africa as slaves. While modern historians debate the over-all impact of the Vandals their name remains synonymous in modern culture with destruction and devastation. The beautiful little OHS site known as Leo Petroglyph in Jackson County, recently suffered another round of what I prefer to call spray paint vandalism. Everyone knows what graffiti is but that is too nice of a name for the damage caused by those who carve or spray paint on such culturally significant areas and/or scenic natural areas. Some of the vandals destruction has been eliminated, some has been only ameliorated, and some has caused permanent damage to the site, which we worked to camouflage. Vandalism breeds vandalism so it is important for us to clean it off as best we could, and strive to keep it cleaned off quickly should it re-appear.

Recently a group composed of OHS staff and volunteers from the Friends of Buckeye Furnace (our partners in operating the site) staged a counter-attack against vandalism at Leo Petroglyph. Other staff the same day worked on trail repairs, improvements and adding a needed railing to a bridge over the stream while five of us worked on the spray paint vandalism.

Following is a step by step photo essay on what it took to try and correct the vandalism as best as we could. We spent a total of about four and half hours or in excess of 22 worker-hours of effort. That does not include the planning, the gathering and purchasing of materials and supplies, nor the travel time to and from the site. I’m hesitant to convert all that into dollar value but it was a costly operation. And as mentioned, the solution does not return the site to a pristine condition but at least the vandalism is no longer obvious. The team included OHS archaeologist Linda Pansing; OHS regional site coordinator, Karen Hassel; OHS AmeriCorps staffer, Maria Pease; Tom Zornes from the Friends of Buckeye Furnace, and myself.

Photo #1  Maria Pease is using a soft, kitchen-type scrub brush to clean off some spray paint from the rock shelter wall. We were committed to use the least invasive and destructive technique possible, as we did not want to cause even more harm to the site than the spray paint itself did. Fortunately, some of the spray paint came off the rock walls fairly easy. Occasionally, dipping the scrub brush in plain water helped a little more. In a number of places, this was all that was needed.

Maria Pease is using a soft, kitchen-type scrub brush to clean off some spray paint from the rock shelter wall. We were committed to use the least invasive and destructive technique possible, as we did not want to cause even more harm to the site than the spray paint itself did. Fortunately, some of the spray paint came off the rock walls fairly easy. Occasionally, dipping the scrub brush in plain water helped a little more. In a number of places, this was all that was needed.

Photo #2  Here Karen Hassel is taking even more care, using an even smaller brush. The pink in this image is spray paint, and the pale, pastel green areas are living lichen plants. The smaller brush is being used to try and leave as much of these natural lichens remaining as possible. At the same time, we tried not to leave behind a bare rock outline of the lettering between the lichens. It took some finesse and care to leave the site looking good! Karen, with her artist background, was especially helpful with this.

Here Karen Hassel is taking even more care, using an even smaller brush. The pink in this image is spray paint, and the pale, pastel green areas are living lichen plants. The smaller brush is being used to try and leave as much of these natural lichens remaining as possible. At the same time, we tried not to leave behind a bare rock outline of the lettering between the lichens. It took some finesse and care to leave the site looking good! Karen, with her artist background, was especially helpful with this.

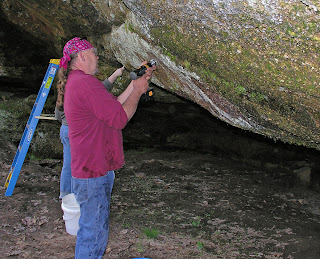

Photo #3  Tom Zornes is taking the attack up a notch. Some of the paint was enamel that would not come off with the gentler approach. Tom has a cordless drill with a brass wire brush spinning at high speed. This was used only after a small brass wire brush was used by hand and did not do the job. Again using the least powerful and least destructive agent possible, while still getting the paint off the rock surface.

Tom Zornes is taking the attack up a notch. Some of the paint was enamel that would not come off with the gentler approach. Tom has a cordless drill with a brass wire brush spinning at high speed. This was used only after a small brass wire brush was used by hand and did not do the job. Again using the least powerful and least destructive agent possible, while still getting the paint off the rock surface.

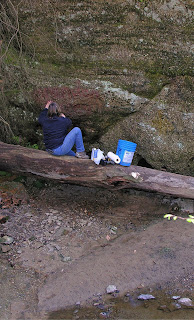

Photo #4  Here Karen is taking it easy not really. She is utilizing a handy fallen dead log to access some spray paint about six feet above the rocky stream bed. This section required a hand-powered wire brush and a little acetone. Fortunately, there was not much lichen or moss on this spot, and paper towels kept the acetone from dripping into the stream below. The bucket caught used towels etc.

Here Karen is taking it easy not really. She is utilizing a handy fallen dead log to access some spray paint about six feet above the rocky stream bed. This section required a hand-powered wire brush and a little acetone. Fortunately, there was not much lichen or moss on this spot, and paper towels kept the acetone from dripping into the stream below. The bucket caught used towels etc.

Photo #5 This section of spray paint vandalism required an extra bit of caution as it was above a narrow ledge about ten feet above the rocky stream bed. We had to scramble up several small foot slots and hand holds to climb up to the ledge. Then Karen and I took turns being strapped in or holding a rope to keep the person from accidentally stepping backwards and off the ledge.

This section of spray paint vandalism required an extra bit of caution as it was above a narrow ledge about ten feet above the rocky stream bed. We had to scramble up several small foot slots and hand holds to climb up to the ledge. Then Karen and I took turns being strapped in or holding a rope to keep the person from accidentally stepping backwards and off the ledge.

Photo #6 This spot also required our most invasive and potentially destructive method of all the techniques we used. While part of this area had paint that was easy to remove, much of it was a very hard, glossy enamel. Here we used a map propane torch to burn off the paint. We already knew from tests that this would remove the paint but it also popped off small flakes of the rock surface would as well! This was far from being a good choice of methods but it was the only method that worked. We actually left some paint in place where it blended in with some of the natural black, green and white deposits in the rock. So we minimized the amount of rock surface damage by removing only as much of the rock and the paint as required to not be able to notice the remaining paint in amongst the natural rock patterns. We did not like thislevel of aggressive removal, but we did not seem to have much alternative. Leaving the graffiti behind would both mar the natural beauty of this fantastic little site, and encourage others to add their own graffiti to it.

This spot also required our most invasive and potentially destructive method of all the techniques we used. While part of this area had paint that was easy to remove, much of it was a very hard, glossy enamel. Here we used a map propane torch to burn off the paint. We already knew from tests that this would remove the paint but it also popped off small flakes of the rock surface would as well! This was far from being a good choice of methods but it was the only method that worked. We actually left some paint in place where it blended in with some of the natural black, green and white deposits in the rock. So we minimized the amount of rock surface damage by removing only as much of the rock and the paint as required to not be able to notice the remaining paint in amongst the natural rock patterns. We did not like thislevel of aggressive removal, but we did not seem to have much alternative. Leaving the graffiti behind would both mar the natural beauty of this fantastic little site, and encourage others to add their own graffiti to it.

Photo #7 This was one of the most disheartening incidents. The vandals used a gritty stone perhaps some of the sandstone/conglomerate native to the site to scrap messages right on the rock inside the shelter between the prehistoric petroglyphs. You can see one of the petroglyphs outlined with charcoal only about an inch away from the fresh writing. This vandalism could have caused permanent damage to these 1,000 year-old petroglyphs.

This was one of the most disheartening incidents. The vandals used a gritty stone perhaps some of the sandstone/conglomerate native to the site to scrap messages right on the rock inside the shelter between the prehistoric petroglyphs. You can see one of the petroglyphs outlined with charcoal only about an inch away from the fresh writing. This vandalism could have caused permanent damage to these 1,000 year-old petroglyphs.

We left this spot to our archaeologist Linda Pansing. Fortunately, the scraping rock was apparently a little softer than the rock with the petroglyphs and Linda was able to scrub it off with the soft brush fairly easy. Easy? That is a relative term. Recall the planning, organizing the supplies, the travel time to this remote site and the actual time of work. All for a couple of minutes of some ones warped idea of memorializing themselves!

Bob Glotzhober