Welcome to Our Summer Interns!

Meet Grayson and Grace—two of our outstanding summer interns at the Ohio History Connection!

This story originally appeared in the March/April 2021 edition of Echoes Magazine, our member publication. For info about membership, visit ohiohistory.org/join.

Abolitionism in America is a well-known, yet often misunderstood chapter in American history. Many of us are familiar with a few of the main figures of the abolitionist movement such as William Lloyd Garrison, Angelina Grimké, John Brown and even Harriet Tubman. These figures and others fought feverishly against the institution of slavery all over the country, both on moral and economic grounds.

However celebrated these icons have been in places like New York and Massachusetts, the role that Ohio played in the overall movement is too often downplayed or sometimes completely overlooked as we tell of the exploits of these great men and women.

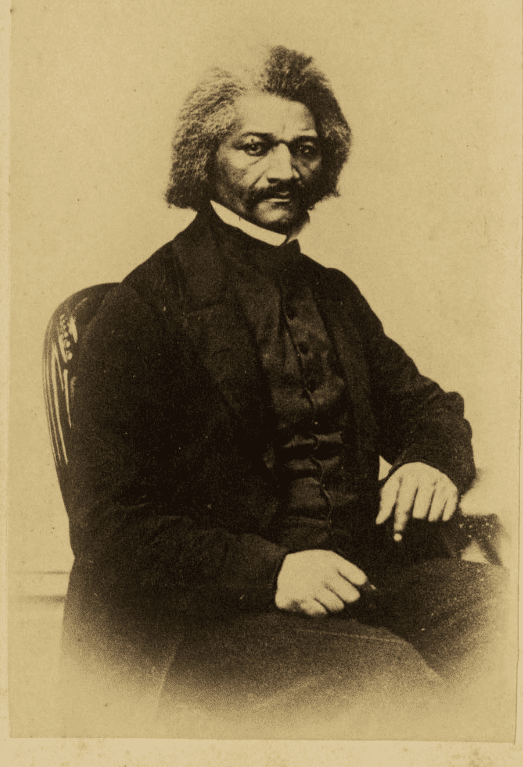

In order to better understand the role that Ohio played in the national abolitionist movement it is critical to discuss how it was viewed by one of the most distinguished abolitionists in American history. This giant of the abolitionist movement was Frederick Douglass, one of the greatest orators of the 19th century, arguably the Age of Oration, who delivered a very consequential speech in Hudson in 1854.

This portrait was featured on the title page of Douglass’s autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave published in 1845. Image courtesy of Library of Congress.

Douglass is often viewed as the most important and visible figure in the American abolitionist movement. Known for giving unfiltered and blistering speeches against the institution of slavery and its supporters, Douglass made numerous stops in the state of Ohio. In fact, he made several trips to Hudson specifically to speak to the city’s hyperactive African American abolitionists directly.

These abolitionists, whether formally organized or not, were largely ignored as the early movement is too often defined as a mostly white, religious movement, while African Americans and women were characterized as passive observers. The attention that Douglass brought to this part of the state forced people to view them and Ohio differently.

DUE CREDIT

Although Douglass’s visits to Ohio highlighted the passion and dedication of the African Americans associated with the movement, they were not typically given due credit for their full contributions to both the local and national abolitionist movement.

Douglass, being formerly enslaved, was himself for a period among those relegated to the shadows until he joined the “organized” movement. He fully understood the internal mechanisms at play and the rabid discrimination African Americans in Ohio faced at the time and wanted to connect this powerful branch with the rest of the movement to ensure it would continue to grow in size and intensity. Ohio would be crucial in that respect.

The speech he gave on July 12, 1854, in Hudson, Ohio was in some regards similar to the more well-known speech given in Rochester, New York, on July 5, 1852, titled, “What, to the Slave, Is The Fourth of July?” but was decidedly less fiery.

Douglass’s Hudson speech, which was a commencement address titled, “The Claims of the Negro, Ethnologically Considered: An Address Before the Literary Societies at Western Reserve College,” was a raw, yet intellectual defense of the literal humanity of African Americans.

Douglass published his 1854 speech at Western Reserve College.

At this juncture of the 19th century, there were numerous arguments being invented to justify not only the continuation of slavery, but also the racist and discriminatory laws, or Black Codes, created to prevent African Americans from fully participating in all that the country offered its citizens.

For example, there were claims that Black people in general were not fully human, but only a lesser civilized subset of the human family, not possessing true manhood. This pseudo-scientific stance was buttressed by assertions that Black people were more closely related to primates than whites and that any form of civilization that appeared on the continent of Africa was only borrowed through their beneficial contact with Europeans.

The explanation of ancient Egypt’s high level of civilization that no one doubted, was that it wasn’t truly a part of Africa and the inhabitants were more closely related to those of the Mediterranean and the ancient Levant, not Black Africa.

This completely removed any semblance of the African presence and influence from one of the world’s greatest civilizations, again relegating Black people to passive observers in world history.

CATERED TO STUDENTS AND FACULTY

Douglass’s Ohio speech was written within this racially intolerant context and catered specifically to the sensibilities of the students and faculty of Western Reserve College, now known as Case Western Reserve University.

Frederick Douglass spoke on July 12, 1854, outside the chapel at Western Reserve College in Hudson. The 1836 chapel, listed in the National Register of Historic Places, still stands on the campus of today’s Western Reserve Academy. Image courtesy of Library of Congress.

Douglass opined that the students present for the address were going to be the next generation of leaders, so he was careful to challenge them by stating that, “. . . the neutral scholar is an ignoble man. Here, a man must be hot, or be accounted cold, or, perchance, something worse than hot or cold. The lukewarm and the cowardly will be rejected by earnest men on either side of the controversy.”

The idea was to use all of the tools at his disposal—history, ethnography, linguistics and religion—to prove the “oneness of humanity.” Once African Americans are viewed as being equal to whites in the eyes of God, then all other arguments have to fall by the wayside. He clearly articulated that the credibility of the Bible was at stake.

Due to a combination of the heavy evangelical ethos of the college and the antislavery environment of Northern Ohio at the time, there was a great interest in hearing Douglass speak. His reputation was of a speaker who never held back and spoke very directly to those who would offend and to those who would defend.

This speech would be his first commencement address, but he ensured it concentrated on the most important question, which, as he put it, was the relation between Black and white. Although very straightforward and unafraid, his speech and delivery was not only a defense of the basic humanity of African Americans, but also a call to heed common sense.

He wanted those in attendance and others around Ohio to recognize the contributions of Blacks to the broader movement. He did so by connecting them to the efforts of Black leaders who contributed to Great Britain’s ending slavery in the West Indies through the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833.

THE PERFECT EXAMPLE OF ABOLITIONISM

He was known for often citing the propensity of African Americans to herald Toussaint L’Ouverture’s revolution in Haiti and how they looked to him as the perfect example of abolitionism. Douglass alluded to the fact that he did not want the largely white, “organized” abolitionist movement to lose sight of its history and those who had already helped lay the foundation from which they built their work.

Much the same way he repeated the phrase in his 1852 speech, Douglass recited on multiple occasions in his Ohio speech the phrase, “This great sin and shame on America.”

That “great sin and shame” wasn’t just the perpetuation of the institution of slavery, but was also the sociocultural, economic and political exclusion of African Americans from most basic applications of American life. He witnessed it in all facets of life, including the abolitionist movement itself, and did not hesitate to point it out.

Frederick Douglass’s 1854 speech to the students and faculty of Western Reserve College was not only a clear and concise call for the end of neutrality in the debate over slavery, but also a demand to recognize the humanity and contributions of Blacks to the movement and world history.

In that moment, Ohio became a focal point in the debate surrounding the people of conscience abandoning their supposed neutrality and speaking out against all that was wrong in American society.

+++++++

Dr. Charles Wash is executive director of the Ohio History Connection’s National Afro-American Museum & Cultural Center in Wilberforce. For information on the museum and upcoming programs, visit ohiohistory.org/naamcc.