Welcome to Our Summer Interns!

Meet Grayson and Grace—two of our outstanding summer interns at the Ohio History Connection!

At the beginning of a New Year it’s traditional to look back on the achievements of the past year. Archaeology magazine does this every January with a list of the top ten archaeological discoveries of the year. I always enjoy looking over the list. It’s fun, for example, to compare it with other similar lists and with your own ideas about which discoveries were the most epic. Whether or not you agree with every pick, however, isn’t really the point.

For me, these top ten lists do a couple of things. They celebrate the highlights of what the discipline collectively accomplished over the last year, but they also inspire us with the reminder that when we do archaeology, at whatever level, that next test unit, pedestrian survey, or magnetometry scan has the potential to reveal one of the year’s big discoveries.

Such lists are not intended to devalue the hard work that goes into projects that don’t produce headline-grabbing discoveries of marvelous sites or spectacular artifacts. The small scatters of flint chips or isolated finds of broken spear points that represent the fruits of most archaeological investigations are important, but it can be hard to appreciate their importance until they are combined and analyzed in thoughtful ways. And that process can take decades or longer.

The heart of the ceremonial landscape on the Salisbury Plain

Something that made just about everyone’s top ten list this year is the discovery of a profusion of new monuments, mounds, shrines and other features at Stonehenge. In my first column of the New Year for the Dispatch I write about the amazing new remote sensing technologies that are revolutionizing (that’s not too strong a word here) archaeology.

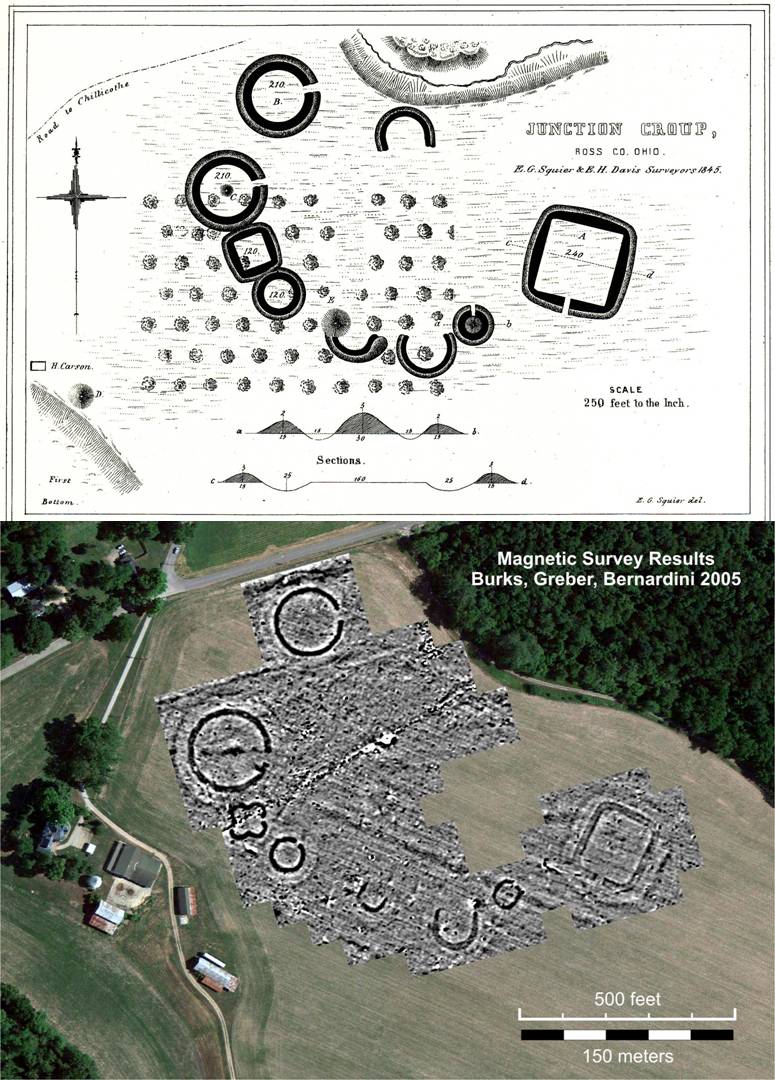

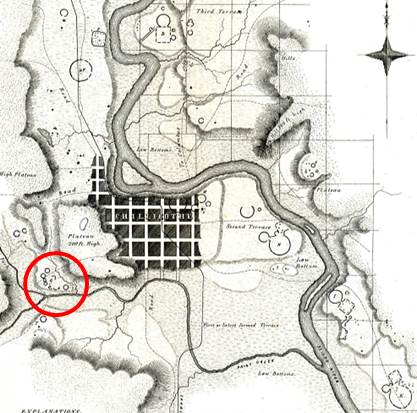

My column compares what English archaeologists are finding on the Salisbury Plain with the re-discovery of the Junction Group in Ohio’s Scioto River valley. This amazing cluster of geometric enclosures was thought to have been totally destroyed by decades of plowing. But, like Westley in The Princess Bride, the earthworks were “only mostly dead.” Miracle Max, in the guise of Jarrod Burks, came along and revealed that the foundations of the earthworks survived beneath the surface of the mostly flattened farm field.

I work with Jarrod quite a bit, so I asked him what it felt like when he first saw the images of those lost earthworks emerging from his data. Here is his reply:

Top image, 1848 map of Junction Works; bottom image, Burks’ magnetic survey results. Note the similarities and differences between the two.

“I definitely had some feelings on the Junction survey! Junction was one of my first adventures on a now-invisible site that had not seen any archaeological attention in 100+ years. I was apprehensive. Even though it is a small site, it is big when you are carrying one little magnetometer. So, I started right by the road on that northernmost circle and within the first hour I knew we had detected it because I was watching the readings and I could see them go up every time I walked over the approximate location of the circle’s ditch. I had to download the data every couple hours and I was holding my breath on that first download. And wouldn’t you know it, cha-ching…a gorgeous circle in magnetic data.

The late N’omi Greber was with me out there that first week and she really wanted to see the square. So, I estimated where its location should be based on faint indications in the aerial photos, shot in the grid way out in the field with the transit, and got the same results–we plopped the survey blocks down right on top of it. Nomi was impressed!

Once the square was done, we then went back to the north edge of the site and proceeded to systematically work our way south. Nomi was not there for the next circle, the bigger one, but she just happened to be there when I downloaded the data containing the quatrefoil. I can remember the feeling of seeing that thing for the first time–thankfully I hadn’t been holding my breath because seeing that quatrefoil for the first time took my breath away…and gave me the tingles all over! Nomi was so very excited while we were standing there next to my truck, looking at the new discovery on my laptop. And that quatrefoil has kept me out there in the farm fields and back lots of Ohio surveying, in all sorts of mind-numbing weather, just waiting to find another very cool feature or enclosure at an earthwork site.

I must admit, I have not been disappointed! There are so many amazing discoveries just waiting to be made. Places like Junction, Steel Group (found an additional 8 enclosures there not previously known), and Moorehead Circle are just the tip of the iceberg!”

The ceremonial landscape of the Scioto River valley. as mapped by Ephraim Squier and Edwin Davis in 1848, showing the location of the Junction Group.

So, Stonehenge and the Junction Group have something in common: our understanding of both is changing thanks to dramatic new discoveries made by remote sensing technology. Actually, these sites may have much more in common than that.

Last January, in the journal Science, Michael Balter reviewed various explanations for the stone monuments of prehistoric Britain, including Stonehenge. He concluded that “monuments served as social glue to bring geographically dispersed communities together in ritual activities.” That’s precisely how some of us think Ohio’s earthen monuments, including the Junction Group, functioned as well.

Thousands of years and thousands of miles apart, two cultures found similar ways to create communities.