Welcome to Our Summer Interns!

Meet Grayson and Grace—two of our outstanding summer interns at the Ohio History Connection!

By Erin Cashion

Updated August 2022

Did you know that August 27-28 is International Bat Night? Celebrate with us by learning more about these adorable and fascinating mammals!

NOT a mouse, and NOT interested in your hair

Alongside snakes and spiders, the bat ranks prominently among the maligned and misunderstood inhabitants with whom we share our world. In popular culture bats have long been associated with rodents, blindness, vampires, and disease.

The word for this flying mammal in some languages reflects one misguided impression; the German word for bat is fledermaus, or “flying mouse”, while in French chauve-souris means “bald mouse”.

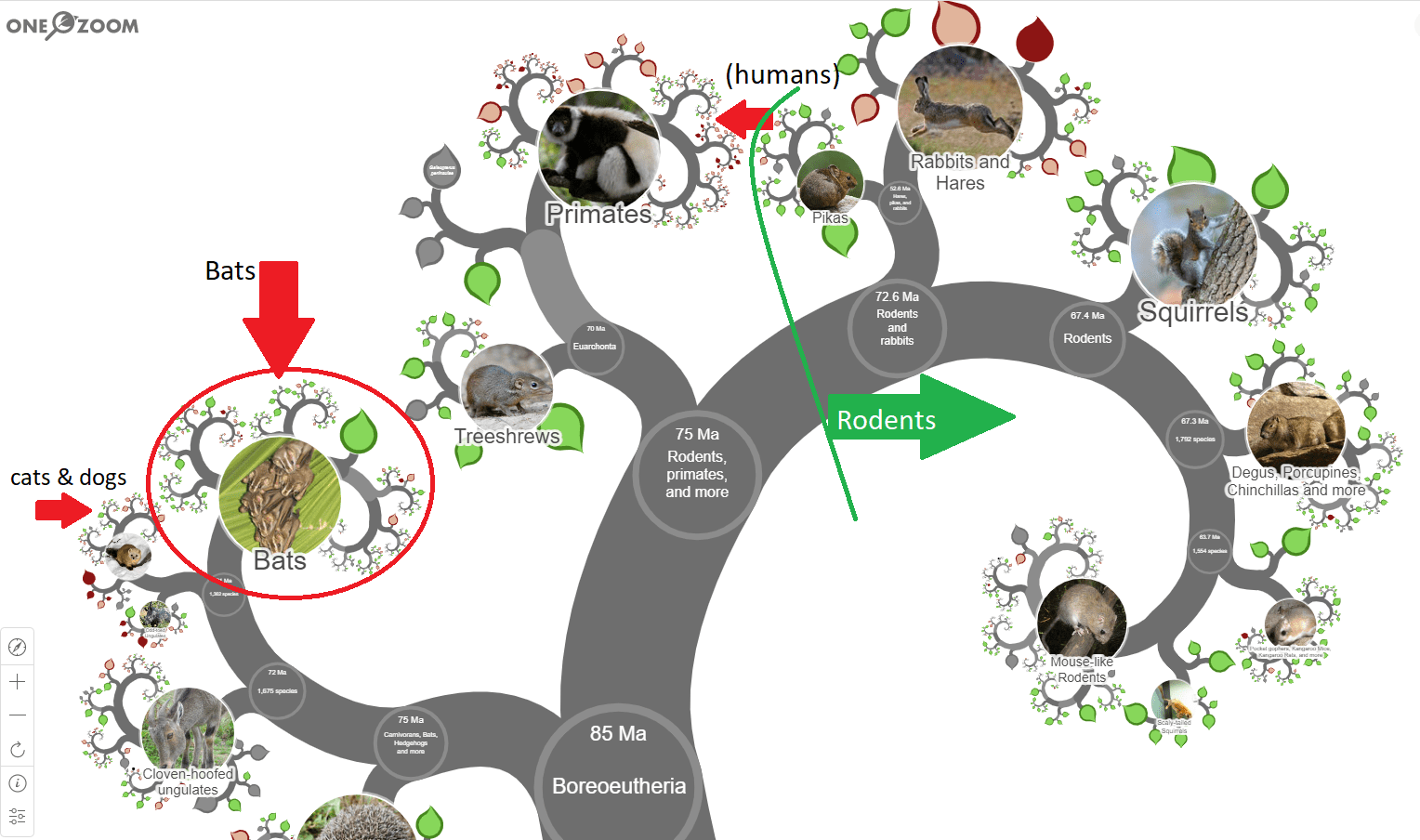

Bats, however, are not even remotely related to rodents! The closest evolutionary branch to the bats is that which led to today’s cats, dogs, bears, horses, pigs, whales, and deer. In fact, primates (i.e. us) are more closely related to rodents than bats! The picture below is a depiction of a phylogenetic tree from OneZoom.org. A phylogenetic tree shows how species are related to each other, a little bit like a family tree shows a person’s ancestry. See the green line and arrow? Everything to the right of them is a rodent. I have included a tiny red arrow at the top indicating where modern humans are located (with the primates), and the other two red arrows on the left side show where cats & dogs and bats are located relative to each other. So bats are really much more closely related to cats and dogs than they are to humans, OR to rodents!

Hours could be spent exploring the detailed and interactive phylogenetic trees at OneZoom.org. Screenshot taken by Erin Cashion.

Giant Golden-crowned Flying Fox (

Acerodon jubatus)

of the Philippines. Photo credit: Gregg Yan

So if bats are not rodents or shrews with wings, what are they? Like all mammals, their early ancestor was something small, nocturnal, and insectivorous. DNA evidence suggests the bats branched off from other placental mammals 100 million years ago, or about 30-40 million years before the non-avian dinosaurs went extinct, but so far the earliest fossil definitively identified as a bat is the 52.5 million-year-old Onychonycteris finneyi. This early bat was capable of flight, but scientists are still debating whether it had the ability to echolocate. By 33.5 million years ago, all 26 modern families of bats had evolved. So bats are really their own thing, and make up the most recent branch of the Carnivora family tree!

Today there are around 5000 species of mammals, and bats alone comprise over 1/5 of them! Bats are divided into two suborders: the Microchiroptera (small, mostly carnivorous bats that echolocate) and Megachiroptera (fruit bats and flying foxes that do not echolocate). Most bat species can easily fit in a person’s hand, but the fruit-eating Giant Golden-crowned Flying Fox of the Philippines is among the largest, with a wingspan exceeding 5 feet.

In Ohio, we have 13 species of bats, including the gorgeous Eastern Red Bat (Lasiurus borealis, at right), the adorable Northern Long-Eared bat (Myotis septentrionalis) and the diminutive Tri-colored Bat (Perimyotis subflavus, formerly known as the Eastern Pipistrelle).

Another misconception is the old adage, “blind as a bat”. While some bat species have eyesight that is relatively poor, no known species of bat is truly blind; even nocturnal species rely on changing light levels to discern when it’s time to become active. Other bats have such well-developed vision that they can detect color at night, making their vision much better than a human’s. Many bat species also “see with their ears” using highly sophisticated echolocation, enhanced in some species by prominences and structures on the ears and nose.

Honduran White Bats (Ectophylla alba). Photo credit: Flickr user Wanja Krah

While bats are frequently associated with vampires and the act of drinking blood, only three species of bats depend on blood as their sole food source, and two of those drink bird blood; the third species does not frequently target humans. All are found in Central and South America. Rather than suck blood through hollow fangs as mythical vampires do, they make an incision with their extremely sharp incisors and lap up the blood. The skin patches on their noses have evolved to be particularly sensitive to heat, and their saliva contains anticoagulants and other compounds that prevent clots from forming. One of these compounds was identified for potential use in stroke victims.

A forklift on a forklift. (DO NOT DO THIS)

Bats are also branded as carriers of disease, particularly rabies, a disease caused by a type of Lyssavirus. There are 1-2 rabies infections in the U.S. per year, so a person living in the U.S. is more likely to catch leprosy or the plague than contract rabies from a bat. And as I learned a few years ago during forklift certification training, a person is also 40 times more likely to die in a forklift accident than die of rabies.

Worldwide, 99% of rabies deaths are due to encounters with rabid dogs, which is not an issue in the U.S. (thanks to successful vaccination programs). Bats are far less likely to carry rabies than skunks, raccoons, coyotes, foxes and unvaccinated pets; however their small size and docility makes bats appear harmless, so people are more likely to handle them. But bats are extremely feisty and will bite readily when handled! As a result over 80% of rabies cases in the U.S. are due to bat bites resulting from direct handling.

The survival rate for rabies in humans is 50% if caught early and treated with the rabies vaccine; however symptoms take 3-4 weeks to develop and can be mistaken for the flu. (For a detailed and informative animated summary of how rabies infects the body, I highly recommend this video by Kurzgesagt.) Once symptoms or prodrome of the virus begins, rabies is nearly 100% fatal if no vaccine was given during the incubation period. Only 6 people worldwide in recorded history have been known to survive rabies. One of these survivors is Matthew Winkler of Lima, Ohio, who was bitten as a 6-year-old in 1970 and began the vaccine series within 5 days of being bitten. He spent nearly 3 months in the hospital receiving intensive care and therapy to address speech loss and partial paralysis due to the neurological damage caused by the virus. He is still living today.

UPDATE 2022 #1: The ongoing SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has brought particular attention to bats as reservoirs for coronaviruses, a large family of viruses that includes the common cold as well as SARS and SARS-Cov-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19). You can find more information about bats and disease here.

The person holding this state-listed Endangered Indiana Bat (Myotis sodalis) has had their rabies vaccine series and the necessary training to handle bats safely. Photo credit: Adam Mann

Keep pets and children away from the bat, call your local wildlife officer or wildlife rehabilitation center for assistance, and finally –don’t kill it. According to Ohio Administrative Code, it is against the law to exterminate a bat, much less a colony of them, unless there has been an exposure to a zoonotic disease (such as rabies) confirmed by a lab.

I must point out that, statistically, mosquitoes are a much greater threat to human health than bats (notice that bats don’t even appear on this chart!). In fact, bats directly benefit humans by consuming thousands of mosquitoes and other insects (some of which damage crops), and are an extremely important part of ecosystems as a whole.

All you have to do to eliminate the tiny risk of contracting a disease from a bat is not handle them.

Flight is energetically expensive, and bats can neither feed around the clock to maintain their high metabolism, nor tolerate very cold temperatures. To conserve energy during periods when temperatures are unfavorable or food is unavailable, all North American bat species enter torpor. During torpor an animal’s metabolism slows, its body temperature plummets, and its heart and breathing rates nearly stop. Torpor may last a matter of hours (i.e. overnight), or it may continue for weeks at a time—a state more commonly known as hibernation.

Schneider’s Leaf-nosed Bat (Hipposideros speoris). Photo credit: Flickr user Seshadri. K.S

In North America bats may migrate south during the colder months as some birds do, or find a sheltered place to hibernate. Many bat species use caves as hibernacula (places where animals gather to hibernate) since the temperature stays relatively warm and constant (around 50 degrees Fahrenheit) during the winter, while other species use caves as daytime roosts. However, for some bat species, using caves as hibernacula has made them especially vulnerable to a new threat.

White-Nose Syndrome (WNS) is an infection caused by the aptly-named fungus Pseudogymnoascus destructans, or Pd. WNS has been devastating bat populations in the United States since its appearance in 2006 and is causing “the most precipitous decline of North American wildlife in recorded history.” The Little Brown Bat (Myotis lucifugus) and the Big Brown Bat (Eptesicus fuscus) are two of 7 bat species in North America that have been heavily impacted.

WNS is named for the white patches that appear on the bat’s noses and other areas where skin is sparsely haired. Photo credit: Marvin Moriarty/USFWS

The origin of Pd was traced to a cave in New York, where it’s thought to have been introduced on the boots of a caver who had recently been spelunking in Europe, where the fungus is native. The fungus does infect European bats but they seem not to succumb to it, having co-evolved with the fungus over many thousands of years.

Unlike our familiar bathroom mildew, Pd thrives in cool, damp environments, such as caves. During torpor a bat’s body temperature is barely distinguishable from its surroundings, making them the ideal substrate for the fungus to grow and thrive. It is spread from bat-to-bat primarily during the winter months when they are gathered close together. So far, the fungus is only killing bats that use caves as hibernacula, and not those that roost in caves during the daytime in summer. Cave roosting bats may be getting exposed to Pd, but since they are only torpid for a few hours at a time, the fungus can’t get established and dies once their body temperature returns to normal.

White Nose Syndrome detection maps by U.S. county are available here and are updated regularly: https://www.whitenosesyndrome.org/where-is-wns

In North American bats, the fungus changes the bats’ wintertime behavior by disrupting their torpor cycle. It is normal for bats to wake for short periods during the winter—in fact it’s when male bats seek out and mate with the unconscious females—but bats with WNS wake earlier, more often, and for longer periods. Sometimes they are found flying during the day or congregating near the hibernacula entrances. Ultimately infected bats die due to dehydration, starvation and exposure before spring, having burned up all of their fat reserves during these wakening periods. The fungus also eats holes in their wing membranes.

WNS was first recorded in Ohio in Lawrence County in 2011 and has been found in 18 counties since that time. In 2013 a hibernaculum in Lawrence County experienced an 80% population decline within a single year. Because most bats produce just one pup a year, populations hit heavily by WNS may take many years, if not decades to recover. One study conducted in 2010 suggested that if current trends continue the Little Brown Bat—our most common species—will become extinct in 16 years.

Northern Long-eared Bat (Myotis septentrionalis). Photo credit: Al Hicks/NYDEC

Thankfully, the news isn’t all bad. Researchers discovered that a common soil bacterium Rhodococcus rhodochrous, when exposed to cobalt, releases volatile organic compounds that keep the fungus from multiplying. This property was discovered accidentally when researchers at Georgia State University were looking for a way to delay the ripening of bananas with R. rhodochrous, and noticed that the treated bananas also had a lower fungal burden. A colony of infected bats was captured last fall, treated, and placed back in their cave inside a special cage. In spring, half of the infected bats had recovered, and were released back into the wild.

While the news is certainly good, finding a way to treat infected bats efficiently (and cheaply)—i.e. without capturing every single infected individual and releasing them once cured—is another matter. The cave ecosystem is a delicate one in which thousands of microbial species exist together in a delicate balance, and there is concern that introducing R. rhodochrous may disrupt that balance by killing off benign or beneficial fungi. Extensive testing will be necessary before bat caves can be “bombed” with the stuff wholesale, but in the meantime, artificial caves such as abandoned mines or bunkers, having no ecosystems to disrupt, can be inoculated against Pd. Some artificial caves have already been constructed specifically for bats and have successfully hosted hibernating bats.

UPDATE 2022 #2: Since the original publishing of this blog in October 2015, WNS has spread far and wide, thwarting any efforts at innoculation or treatment. Innoculation does not confer immunity, so treated bats became reinfected when reintroduced to the wild. The fungus has simply outpaced any attempts to contain it, and WNS is here to stay. The Northern Long-Eared Bat, currently listed as Threatened, was proposed for inclusion on the federal Endangered Species list, in part due to the impact of WNS on their populations.

But the worst predictions have not yet come to pass. Researchers are minimizing monitoring to reduce wintertime disturbance, which stresses the bats and increases the likelihood that they will die from WNS infection. Populations of some species have stabilized, albeit at dangerously low levels, and some hibernacula are even showing signs of population recovery – indicating the bats may be evolving resistance to the fungus, as the bats in its native Europe did. It is still a dangerous time for bats, but the future is not quite as dim as it was in 2016. Learn more about bat population recovery from WNS here.

I’m so glad you asked! Here are a few good resources online where you can learn about bats and directly help support and fund their conservation:

https://www.whitenosesyndrome.org/static-page/how-you-can-help

https://www.bats.org.uk/support-bats

Below, your daily dose of cute: An Australian Flying Fox wildlife rescuer works hard to save a whole lot of what resembles furry baby dragons.