Ohioans on the Move

A news snippet detailing the Drew's membership to the Archaeological Society of New Mexico in The Albuquerque Morning Journal, 1917. (Library of Congress)

Although we cannot be sure the means most of the objects featured in this blog were obtained - whether they were bought outright during travel to Sa Fe or purchased via mail order catalog - one object in particular can be more illuminated.

Irving Drew, a prominent Portsmouth shoe manufacturer, and his wife Ella Drew collected a muna from Santa Fe (above, right). On the bottom of the muna are inscribed details, "Santa Fe, New Mexico 1907; Tesuque Pueblo"

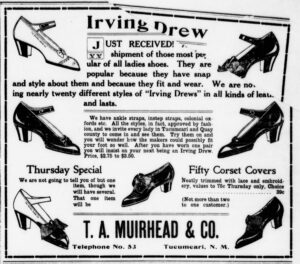

An advertisement for Irving Drew shoes in a New Mexico newspaper, The Tucumcari News, 1901 (Library of Congress)

It appears that by 1901 the Irving Drew brand was being advertised in New Mexico newspapers (left). The arrival of the brand is commonly seen being celebrated by local shoe shops throughout the early 1900s. The success the brand in the southwest may have spurred a 1917 trip to Santa Fe. On February 19, 1917, the visitation of Mr. and Mrs. Drew to the State Museum was reported by The Albuquerque Morning Journal. Ella Drew became a member of the Archaeological Society the next day (right).

It is rare for a single object within our Ethnographic Collection to lead to the discovery of such newspaper accounts but it is moments like this that bring satisfaction to endless research. For those objects that have less clarity, they remain important waymarkers of the interests and movements of Ohioans in an increasingly interconnected world.

Each object in the Ethnographic Collection is a testament of national and international exchange. Ohioans not only left with objects but also imparted tangible, and distinctly Ohioan, economic and cultural ideals to the places they visited in the 19th and 20th centuries, an exchange that still occurs to this day when you board an airplane or venture on a cross-country trip to seek a little adventure in your life.

Into Modernity - Further Reading

Over one hundred years later, the making of the once non-traditional ceramic souvenirs has become cemented as a genuine expression of the Pueblo identity. Contemporary examples are visible in Tewa Pueblo folk art munas, modern Cochiti storyteller figures, and in the work of Pueblo artists like Virgil Ortiz whose mono figures regularly appear in art exhibits worldwide.

For the sake of brevity, I have omitted the nerdiest of details such as changes in the figurative forms across the decades and the evolution of Santa Fe curio shop advertisements. For those so enticed, below is a list of further reading.

Anderson, Duane

2002 When Rain Gods Reigned: From Curios to Art at Tesuque Pueblo. Museum of New Mexico Press, Santa Fe.

Batkin, Jonathan

1999 Clay People: Pueblo Indian Figurative Traditions. Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian, Santa Fe.

1999 Tourism is Overrated: Pueblo Pottery and the Early Curio Trade, 1880-1910. In Unpacking Culture: Art and Commodity in Colonial and Postcolonial Worlds, edited by Ruth B. Phillips and Christopher B. Steiner, pp. 282-297. University of California Press, Berkeley.

Hayes, Allan, John Blom and Carol Hayes

2015 Southwestern Pottery: Anasazi to Zuni. Taylor Trade Publishing, Lanham, Maryland.

The gang's all here. All unattributed images photographed by Marie Swartz.