With a substantial grant from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission, The Ohio History Connection has embarked on a two-year project to thoroughly describe several archival collections about our 29th president, Warren G. Harding. Archivist Wendy Korwin will be contributing regularly to our History Blog as she delves into (many, many) boxes of Harding’s papers, photographs, and newsreels. We thought we’d introduce this series of posts by asking her a few questions. Read more in the coming months about her work and about President Harding!

Would you like to introduce yourself? What do you do at the Ohio History Connection?

My name is Wendy, and I’m the archivist for the Harding project. I formerly worked in the State Archives, which is also part of the Ohio History Connection. Before moving to Ohio, I studied and worked on the east coast, as a graduate student in American Studies at the College of William & Mary in Virginia and as an archivist in Providence, Rhode Island.

Project archivist Wendy Korwin stands with boxes of President Harding’s papers kept in the Manuscripts and Audiovisual Vault at the Ohio History Center

Can you tell us about the Warren Harding papers and their history?

The largest collection I’ll be working with is Harding’s presidential papers, which comprise more than 900 boxes of material – whew! They trace Harding’s career from his early days in Marion, where he ran the Marion Daily Star newspaper and became active in Ohio politics, serving as a Republican state senator (1899-1903) and lieutenant governor (1903-1905) before unsuccessfully running for governor in 1910. Other parts of the collection document his term in the U.S. Senate (1915-1921), his 1920 campaign for president, and his brief term in the nation’s highest office (1921-1923).

This collection has a pretty fascinating and complicated history of its own. Shortly after Harding’s death, his widow Florence Kling Harding supposedly told the Library of Congress that she had burned “practically all” of her late husband’s papers.[1] That’s not quite true, though she did, it seems, examine and cull the correspondence from his private office in the White House. There are descriptions of her “committing certain items to the blazing fireplace” in the weeks following her husband’s death.[2] I suppose we’ll never know exactly what, or how much, was removed, but I’m interested in thinking more about Florence’s role as a *creator* of this collection, not simply a censor or destroyer. That might be a topic for a future blog post; stay tuned!

Other large chunks (not a technical term) of the Harding Papers were kept in the Star’s offices in Marion and by Harding’s secretary, George B. Christian, Jr., who organized about 100 cubic feet of material and then left it in the White House basement. Workers only discovered that portion in 1929, while doing repairs during the Hoover administration. Eventually, these different groups of the President’s papers came under the stewardship of the Harding Memorial Association, as stipulated by Florence in her will. The Ohio History Connection (Ohio Historical Society at the time) negotiated with the Memorial Association to secure the donation of Harding’s papers in the early 1960s. They were opened to researchers for the first time in April of 1964 and microfilmed several years later with another grant from the National Archives.

This is not the whole story (by far), but if you’re interested in learning more about what archivists call “provenance,” a good place to start would be with the introduction to the microfilm edition, which you can read on Ohio Memory. These papers took a circuitous path to their current home in our manuscripts vault. Honestly, I don’t know very much about it yet, but as I get started on this project, I’m trying to understand more. I see the marks of my predecessors on the papers I handle every day: dates jotted in pencil at the top of some documents, and numbers stamped by Harding Memorial Association on every page. For me, that’s part of the collection – folks handled these documents and made decisions about what should be here, what shouldn’t, and how it should be organized, decades before I came along.

For this project, we won’t be re-ordering material because we want future researchers to be able to follow existing citations. My main job is to add info, what archivists call “descriptive metadata,” that will open this material up to new kinds of research and make it relevant to new users.

Give us more details. What does your day-to-day look like?

Like lots of people, I spend hours in front of a computer. Unlike lots of people, I also have a box of presidential papers on my desk. Thanks to my colleagues, those papers have already transferred into acid-free boxes and folders, and their “original” labels transcribed (I feel like that has to be in quotes, given my answer to your previous question). I can explore my process in more detail in future blog posts, but basically, I use a tool called ArchivesSpace to create detailed descriptions of what’s in those boxes.

Loading spreadsheets of data for MSS 345, Warren G. Harding papers, into ArchivesSpace

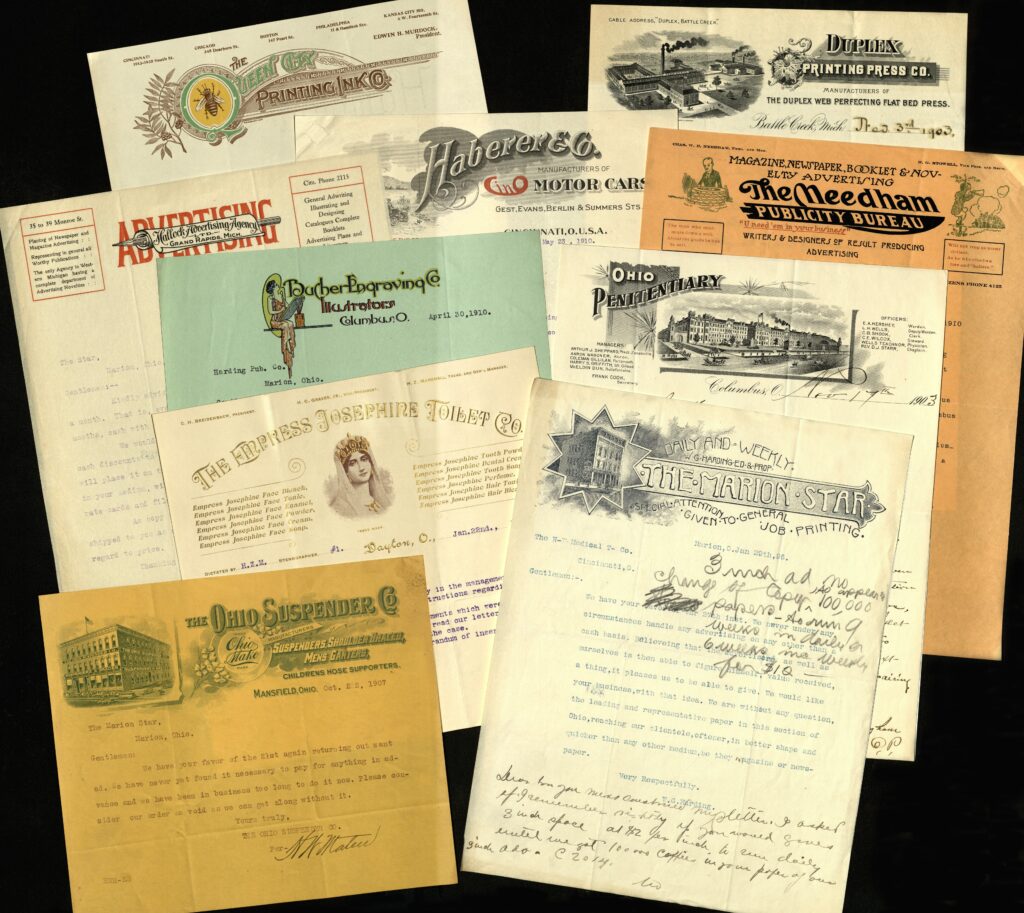

I spend a lot of time essentially tagging people in catalog records. If you wrote a letter to Harding, I care about that, so I create an entry for you in our catalog and link your name to the folder where that letter appears. Right now, I’m working in the early part of the collection, where there is a lot of business correspondence from the Marion Star. I’ve created entries for newspaper editors, advertisers, postmasters, and other individuals and businesses who connected with the Star. Sometimes, a letter about ordering a railroad car’s worth of paper will include a little note wishing Harding well in an upcoming state election.[3] You can see how business and politics intersect, and start to extrapolate influential networks.

There are other people who are harder to identify, like printing press operators who dash off handwritten notes to Harding because they’re looking for a job. I often use clues from their letters to search for them in Ancestry, where Census records and city directories help me create those personal entries, called “agents” in ArchivesSpace. The authors of these letters sometimes elaborate on their technical skills and personal attributes (nearly all of them mention that they don’t drink). I like to imagine a genealogist learning more about one of their ancestors through these job applications. Maybe their great-great-great aunt was a typesetter who was offered a job at the Star and turned it down![4]

What is your favorite thing you have found in the collection so far?

As I mentioned, right now I’m cataloging papers related to running the Marion Star. These documents have certainly expanded my idea about what can be found in a collection of presidential papers. Letterhead is some of my favorite printed material to look at:

Examples of letterhead from the 1890s and early 1900s found amongst the records of the Marion Daily Star

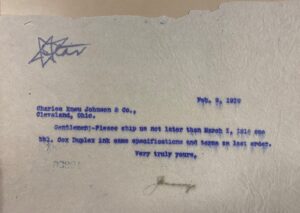

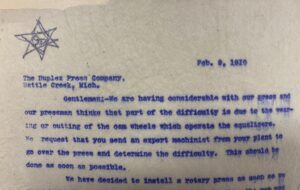

I find these items beautiful, and strange. The letterhead from the Ohio Penitentiary doesn’t look all that different from that of the Ohio Suspender Company. It’s something I need to think about more. But to answer your question about favorite items in the collection, two of them might be Malcolm Jennings’s experiments with letterhead design:

Jennings was a close associate of Harding’s who came to work for the Star in 1909. He took over much of the daily correspondence, and on February 9, 1910, we can see him trying out some new ideas. I haven’t seen any evidence of these designs in print yet, but I’m looking forward to seeing if they pop up later in the collection!

Notes