This article is an extended story from an original feature in our September/October 2025 edition of Echoes Magazine. Echoes Magazine is a free bi-monthly publication that Ohio History Connection Members receive. For more information on becoming a member, visit ohiohistory.org/join.

If you want to know MORE about the U.S.S. Shenandoah and the Ohio History Connection's collections about the airship, check out our curatorial blog on the topic.

By Robin Yocum

Just before 2 a.m. on Sept. 3, 1925, the U.S.S. Shenandoah crossed over the Appalachian foothills, about 3,000 feet above Wheeling, in West Virginia’s northern panhandle. Despite the late hour, the locals were awake and hoping to catch a glimpse of the famed airship in the night sky. The ship’s radio operator would note in his record that his airship was greeted with whistles and bells, and red flares that were set off atop a high hill.

The warm welcome and the sight of the lighted hillside probably brought smiles to the faces of men who had only three hours to live.

The Shenandoah crossed the Ohio River at the village of Bridgeport and continued westward, 126 miles from that day’s destination of Columbus, where the pride of the U.S. Navy air program and the first lighter-than-air rigid airship constructed in the United States was to be on display at the Ohio State Fair.

At the helm of the Shenandoah was Lt. Cmdr. Zachary Lansdowne, an Ohio native, who was on his final mission on the airship. After the six-day public relations tour through the Midwest, Lansdowne was to be reassigned to a post at sea, a move necessary for his desired promotion to full commander.

The 36-year-old Lansdowne had been uneasy about the trip, and he had warned his Navy superiors of the dangers of late-summer storms in his native Midwest. A cautious navigator, Lansdowne said the storms could be fatal to the massive Shenandoah, and he wanted to push the tour back closer to the Sept. 21 end of summer.

But the tour was important to the Navy, and it had already been postponed by several weeks. Lansdowne’s request for another two-week delay was denied by his Navy superiors, who had publicized the tour and were anxious to show off the Shenandoah. Thus, at 3 p.m. the previous afternoon, the Shenandoah left the Navy’s air base in Lakehurst, N.J., and headed west at about 70 miles an hour.

No sooner had the Shenandoah crossed into Ohio than Lansdowne’s fears were realized. The airship was continually buffeted by high winds as it struggled to make headway. Excerpts from the ship’s log, reprinted in the Sept. 14, 1925, issue of Time magazine, noted:

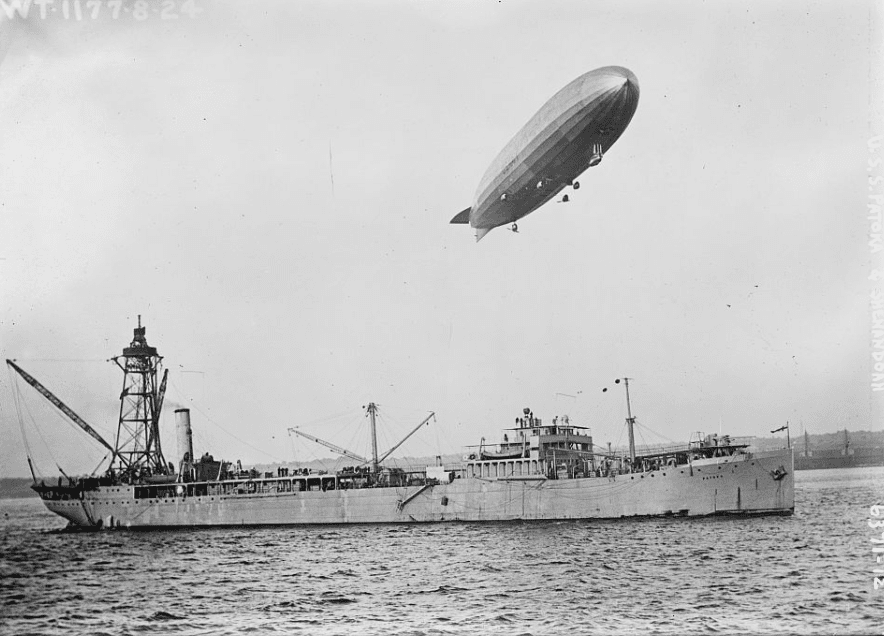

The USS Shenandoah flying over the USS Patoka, 1924.

2:10 a.m. – “ . . . see lightning flashes directly ahead”

2:30 a.m. – “Strike strong head winds and see storms both northwest and southwest in distance. Believe we can ride them without trouble.”

3:50 a.m. – “Storm worst we have encountered to date.”

4:55 a.m. – “Members of crew called from gondola pit and sent into runway to aid in keep ship on even keel. Lightning increasing in intensity. Hope to ride out storm soon. Pleasant City seen in distance . . . wind increasing in volume, get chance to . . .”

Those were the last words he wrote.

At about 5 a.m., over the tiny Noble County community of Ava, the Shenandoah was hit with high winds and updrafts. The ship’s command center, which was in a steel gondola suspended below the hull by cables, was battered, tossing about its crew, including Lansdowne. At one point, witnesses said the nose of the Shenandoah inverted and pointed skyward as the airship began rising at an estimated 1,000 feet a minute, too quickly for the eight safety valves on the gas cells to release enough helium to help it lose buoyancy and regain control.

As the girders supporting the more than 78-foot-wide hull began to groan, Lt. Lewis Hancock in the gondola said, “There she goes.”

Eighty-five miles away in Columbus, Master Sgt. I.J. O’Brien, the chief radio operator at Fort Hayes, had been at his desk all night, monitoring the progress of the Shenandoah. According to a story in that day’s Columbus Evening Dispatch, the last transmission from the airship was received at 5:10 a.m. It was, simply, “I’m losing my seat.”

***

On Sept. 3, 2025, a century will have passed since the wreck of the U.S.S. Shenandoah. The crash of the airship was the 1925 equivalent of the Space Shuttle Challenger and Columbia disasters.

The Shenandoah was the first lighter-than-air rigid airship to be engineered and constructed in the United States. At the time, it was the largest in the world at more than an eighth of a mile long. It was a source of amazement to anyone who saw it, and a source of great pride for the Navy. Shortly after its construction, the Shenandoah made a 19-day, 9,000-mile tour of the country, leaving Lakehurst, N.J., for San Diego, up to Washington state and back. It was a wildly successful trip and only helped to endear the airship to Americans.

It was the crash of the Shenandoah, however, that endeared it to Noble County, Ohio. A hundred years after it broke into three pieces and fell into these Appalachian hills, it remains the county’s most significant historical event.

Photograph of spectators surrounding the Shenandoah airship wreckage, September 1925.

Noble County is in the heart of Ohio Appalachia. Its county seat, Caldwell, is 25 miles north of Marietta, the city that sits at the confluence of the Ohio and Muskingum rivers and was the first settlement in the Northwest Territory and what would eventually become Ohio. Noble was the last of Ohio’s 88 counties to be formed. Portions of its neighboring counties – Guernsey, Monroe, Morgan and Washington – were pared off to establish Noble in 1851.

It was founded by Samuel Caldwell and James Noble, one of the area’s earliest settlers. Caldwell was an established farmer who wanted to create a town that would steal the county seat from nearby Sarahsville. He charted out a town that would bear his name and donated land for the construction of a courthouse and jail. When he convinced the Bellaire Zanesville & Cincinnati Railway – the Bent, Zigzag, and Crooked, as it was known to the locals for its twisting route through the eastern Ohio hills – to bring a line through his town, he became a local hero and secured a county-wide vote to move the county seat to Caldwell.

Doug Brandon is a volunteer docent at the Noble County Historical Society Museum, which sits on the downtown square and is housed in the old county jail and sheriff’s residence. (The sheriff’s second-floor bedroom was across the hall from the two cells reserved for female and juvenile offenders. Men were housed in three cells on the first floor.) Brandon, a former funeral director and Church of Christ minister, isa font of information on county history.

He points out that the Drake oil well, drilled near Titusville, Pa., in 1859, has long been known as the first oil well in the United States. While that is true, it was not the first well to produce oil. That distinction belongs to the Thorla-McKee well, which was located just southeast of Caldwell along Frostyville Road.

In 1814, Silas Thorla and Robert McKee dug a brine well for badly needed salt on the frontier when they accidentally struck oil, which was probably a bit of a nuisance at the time. Not wanting the oil to go to waste, the men sopped it up with blankets, wrung it into jars and sold it as Seneca Oil, a digestive elixir and tonic for all that ailed you. The well has been preserved and fenced off in Thorla-McKee Park.

There’s a monument to John Chapman, a.k.a. Johnny Appleseed, near Dexter City, where his father built a home on the banks of Duck Creek; family members are buried in Chapman Cemetery. “You know,” Brandon said, pointing to a doll model of Chapman at the museum, “There is no documented evidence that he ever wore a pot on his head.”

Noble County also was home to John Gray, the last verified Revolutionary War veteran. Gray reportedly knew George Washington and fought at the Battle of Yorktown in 1781. He died on March 29, 1868, at the age of 104 years, two months and 23 days, and is buried at McElroy Cemetery in Hiramsburg.

As the tour of the museum wound down, Brandon walked to the rear of the first floor to one of the three cells previously reserved for male offenders. “This is what you came to see,” he said. The cell houses the museum’s display of the crash of the Shenandoah, with pieces of the girders and sections of the gas cells that held the airship aloft. There are framed newspaper front pages of the Zanesville Times-Recorder, where a headline erroneously refers to the rigid airship as a blimp, and the defunct Zanesville Sentinel.

Given the scope of national interest in the crash, the display is modest. The museum that people drive to Noble County to see is located in a front yard on Wargo Road in Ava, a stone’s throw from where the Shenandoah’s stern landed after it broke apart. The traveling Shenandoah museum is housed in a 30-foot camper and owned by Theresa Rayner. “I grew up here in Ava, but I married into the Shenandoah,” she said.

Sink from the U.S.S. Shenandoah on display

Rayner’s late husband, Bryan, became obsessed with the Shenandoah when he was a boy. Obsessed might not be a strong enough word. Theresa was the absolute love of his life, but she was running hard just to stay ahead of the Shenandoah. Bryan’s grandfather owned the farmland on which two of the three parts of the Shenandoah fell, including the property where Lansdowne met his death when the control center gondola fell.

Over the years, Bryan collected parts of the Shenandoah. He was a third-generation mechanic and the owner of an automobile repair shop, Rayner’s Service & Towing in Ava, and was interacting with people all the time. They knew of his interest in the airship and over time, as people died and relatives found parts of the Shenandoah in attics and basements, they would be offered to Bryan.

“People would show up and say, ‘Hey, I found this, do you want it?’” Theresa said. “We had a storage room off the garage, and it was stuffed full of Shenandoah stuff. Other people would stop by wanting to see the collection, and Bryan would ask me to run up to the garage and get stuff out of the room. I finally told him, ‘Find a place to put this stuff. I’m tired of dragging it out of the garage all the time.’”

Bryan bought a camper and created the first mobile museum, building the display cabinets himself. However, as the collection grew, he bought the current trailer and hired a designer and carpenter to create museum-style cabinets. It’s a first-class operation that includes 250 original photos, a six-foot-plus section of girder, swatches of the gas cells and the outer skin of the airship, a handset and headset from the ship’s intercom system, magazines, caps, books, various pieces of the ship, a detailed model of the Shenandoah, and trophies from the Rayners’ participation in the Pumpkin Festival in nearby Barnesville. A local man donated six rings that he made from the Duralumin girders that he melted down. A foundry worker, who had been tasked by the government with scrapping the massive frame of the Shenandoah, made a heavy chain and donated it.

“He swore that chain was stronger than anything you could buy in a store,” Theresa said.

Another man brought in a Duralumin sink from the ship that his family had for years used as a hanging planter. There are cufflinks and Naval buttons that people found at the crash site with metal detectors, and an ashtray embossed with U.S.S. Shenandoah. (Rayner notes that, according to his family, Lansdowne was a Chesterfield smoker.)

She has a 78-rpm record and a player piano roll of The Wreck of the Shenandoah, which was recorded by country singer Vernon Dalhart.

At four o’clock next morning

The earth was far below

Then a storm in all its fury

Gave her a fatal blow

For hours they bravely struggled

They worked with all their might

But the storm could not be conquered

And the ship gave up the fight

Mounted beside each item in the traveling museum is a tiny cardboard placard, on which is printed the name of the donor. While impressive, the collection also harkens back to an unfortunate chapter in the Shenandoah saga.

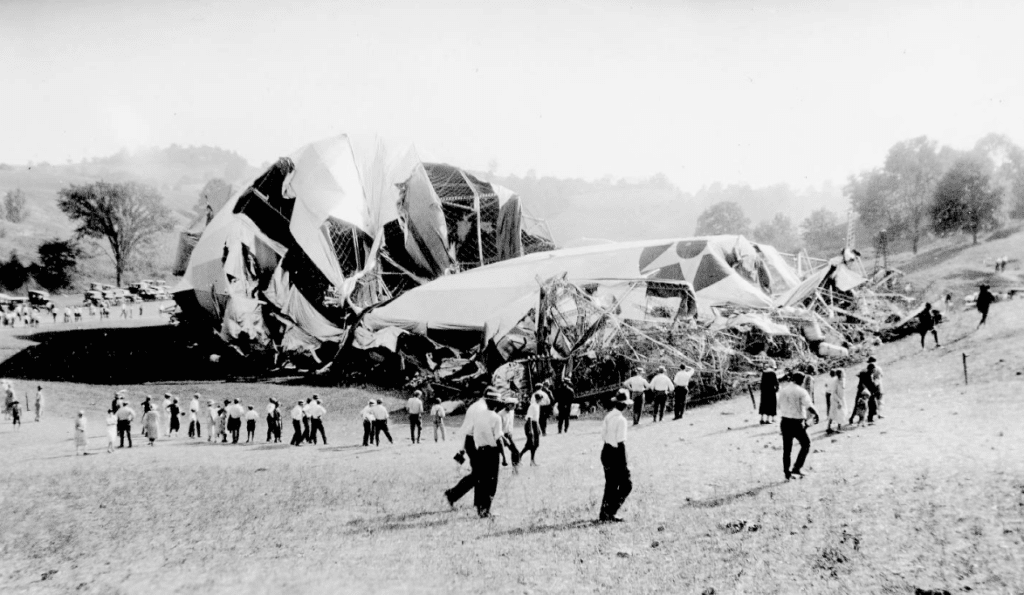

In the chaotic aftermath of the crash, people from near and far flocked to see the airship’s remains . . . and promptly looted them. It became a circus-like atmosphere, with people scavenging for souvenirs and locals stripping the behemoth of its skin. “Like hordes of flies, they swarmed in from all directions over the rolling Noble County hills,” wrote C.H. Chappelear in the Sept. 4, 1925, Zanesville Times Recorder.

The owner of the property where the stern fell reportedly began charging admission to see the wreckage – $1 per carload and 25 cents for individuals – and set up a concession stand of sorts, charging 10 cents for a glass of water.

“It was the 1920s and Noble County was an extremely poor area,” Rayner said. “I think a lot of local people looked at that tangled mess and thought, ‘What are they going to do with it?’ Bryan’s grandmother had a piece of a gas cell. It was material they could use on the farm. I’m not trying to justify looting, but it was a different time and place.”

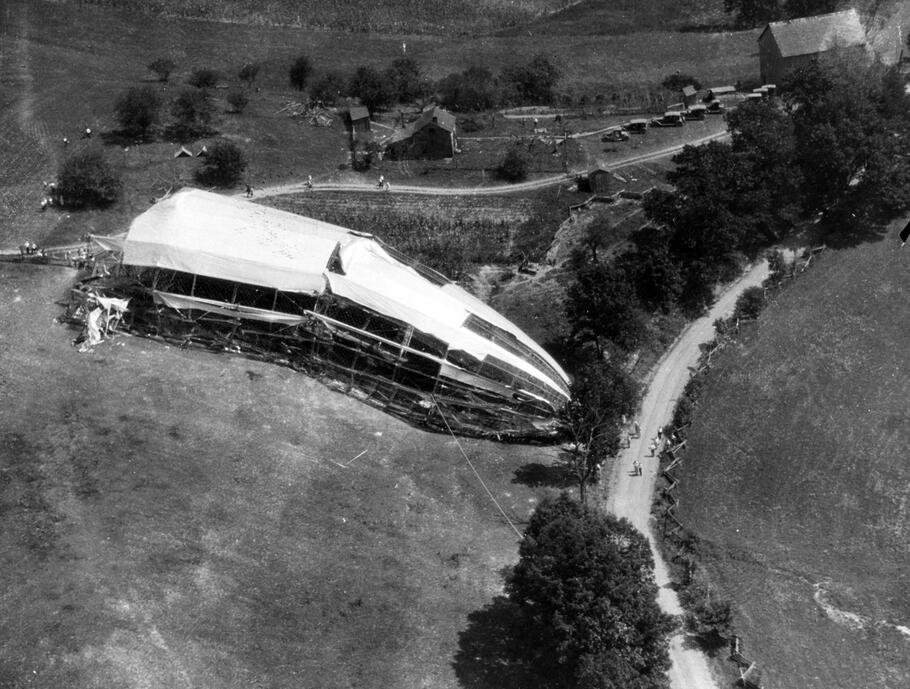

Photograph of the Shenandoah airship wreckage, September 1925 courtesy of the Smithsonian National Air & Space Museum

Estimates vary, but some reports put the number of scavengers in the thousands by noon the day of the crash. Logbooks, instruments and sections of girder as long as eight feet were hauled off. There are stories of the Shenandoah’s waterproof skin being taken and used to make car tarps and raincoats. The photos in the traveling museum show a progression from the first day to the third as the airship appears to decompose.

Navy officials began going door-to-door looking for looted items – Rayner said they were primarily looking for logbooks and instruments – and troops from Fort Hayes and the Ohio National Guard were called in to protect the sites and stop the desecration.

In the museum are two lampshades that a local woman made from cotton cloth taken from the Shenandoah. “Edna Nicholson gave them to me,” Rayner said. “Edna said her mother kept the cloth, and when the lampshades got bad, she used the material to make new ones. I don’t know how she got it or what part of the ship it came from, but she held onto it over the years. In those days, people didn’t throw things away, and that was valuable material to have around.”

One story told of a farmer near the community of Sharon who was caught hitching the bow section of the Shenandoah to his tractor. When a National Guardsman asked what he was doing, he said he was going to haul it to his farm and charge admission to see it. He was promptly sent on his way, sans the bow.

The most disturbing tale was the disappearance of Lansdowne’s U.S. Naval Academy class ring. When his body was discovered, his ring was missing. A century later, how it became missing is still a mystery. Of course, one morbid theory is that one of the early visitors to the crash site took it off his finger. Another, more sanitized theory was that it came off his finger in the crash and was simply lost in the mayhem that followed.

In a Sept. 8 letter to FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, Special Agent E.J. Connelley of the Cincinnati field office stated there had been “wholesale looting at the scene of the wreck and also possibly thefts from the person of dead members of the crew.” Later in the letter, Connelley wrote, “Practically everything is gone except the frame.”

In a Western Union telegram sent to Hoover from the Cincinnati field office, an agent identified only as Eckhart said agents were trying to determine if Lansdowne’s gold watch – possibly the one presented to him by the citizens of Greenville – and money had been taken from his body. The telegram stated, “We have nothing on the ring, but have leads on supposedly gold watch.”

Eckhart noted that parts of the airship had been on display in the east-central Ohio communities of Newark, Zanesville and Marietta, and in West Virginia in Wheeling and Parkersburg, “and other points.” Rayner said she heard stories of shop owners displaying parts of the Shenandoah in store windows.

Hoover wrote back in a letter dated Sept. 9, “I am personally interested in endeavoring to recover the effects of Commander Lansdowne. He was a close personal friend of mine and his wife had been employed in the Bureau of Investigation here in Washington in my own office before marrying Commander Lansdowne.”

Eleven years after the crash, Faye Larrison, who was then living on the property where Lansdowne’s body was found, was weeding her garden when she saw something shiny on a mustard plant. Upon closer inspection, hanging like a Christmas tree ornament from the stem, was Lansdowne’s ring. Larrison reported the find and FBI agents were sent to recover the ring, which was returned to Lansdowne’s widow.

Rayner isn’t sure if either version is true. However, she is friends with Lansdowne’s granddaughter, Julia H. Hunt, who said that the ring was personally returned to the family in perfect condition by Hoover. Lansdowne’s widow began working for Hoover when she was 19 years old, Hunt said.

Was the ring buried in the crash and finally resurfaced, miraculously hanging onto the stem of a mustard plant, or did someone with a guilty conscience put the ring where it might be found? It’s one of many questions about the wreck of the Shenandoah that continues to linger. All that is known to be true is that the ring eventually found its way back to the Lansdowne family. Hunt said one of her brothers now has the ring.

***

The United States was late to the game when it came to airships, and the country’s first two ventures into the field ended in fiery disasters.

Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin founded his company, Luftschiffbau Zeppelin, in 1908. (Luftschiffbau is a German term that translates to “building of airships.”) Germany put them into military use on Oct. 19, 1917, when 11 Zeppelins flew a nighttime bombing raid over England, killing 36 people.

As the Zeppelins made their way back to Germany through headwinds and fog, several wandered over Allied territory and French fighter pilots forced one of the airships, the L49, to the ground. It was subsequently taken back to England where Britain began reverse-engineering it for its own fleet.

That same year, the United States also purchased the Roma, a 410-foot, semi-rigid airship from Italy. It went into service with the US Army Air Service in November. A little more than three months later, on Feb. 21, 1922, while on a test flight over Norfolk, Va., the Roma suffered a problem with its rudder and dove toward earth from 1,000 feet. Just before hitting the ground, it struck power lines that caused the hydrogen-filled airship to explode and burn, killing 34 of the 43 men on board.

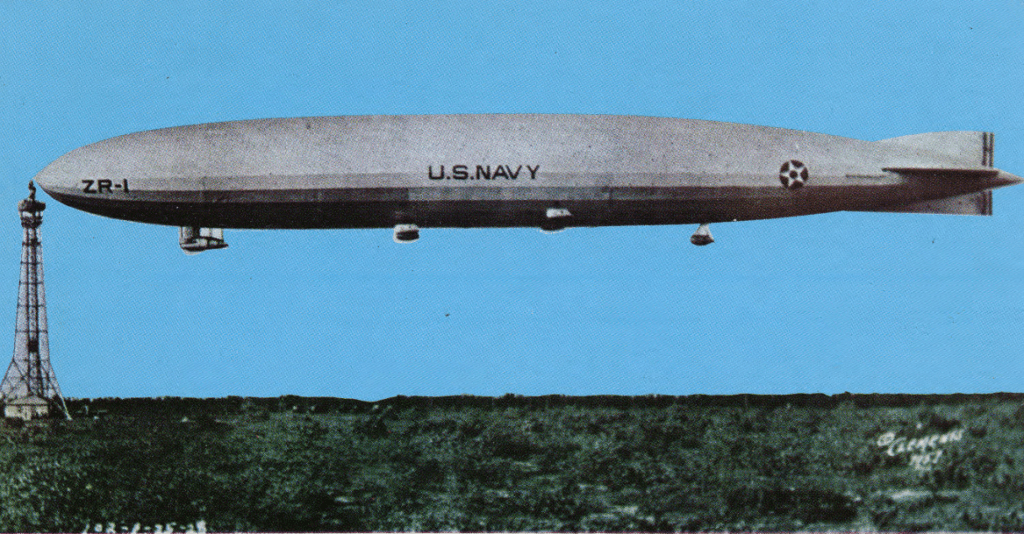

According to documents provided by the Naval Historical Center, the planning stage for the first American-made airship, the ZR-1, began in September of 1919. The following year, construction material was delivered to the Naval Aircraft Factory in Philadelphia to be made into the airship’s components. Once completed, they were moved by truck and rail to New Jersey for assembly.

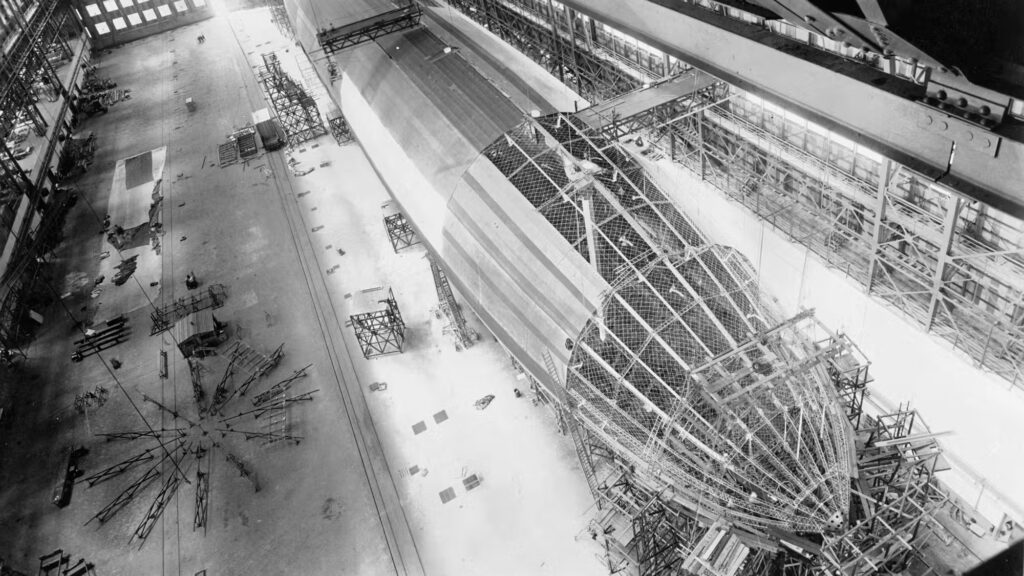

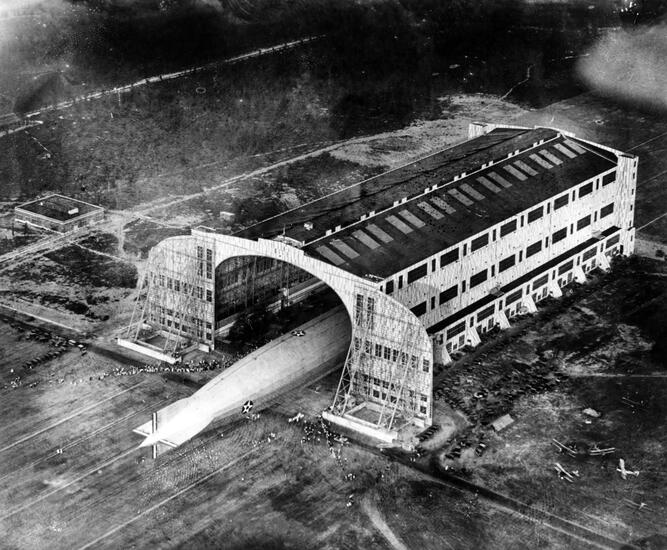

On June 24, 1922, construction began on the lighter-than-air rigid airship that would later become known as the U.S.S. Shenandoah at the huge, 966-foot-long Hangar One at Naval Air Station Lakehurst.

When the Armistice was signed in November 1918, work on the British R38 was suspended due to budget constraints. Anxious to get into the airship race, the United States purchased the R38 and completed its construction in England. At 695-feet in length, it was the largest airship in the world. Its first test flight was on June 23, 1921. Two months later, on Aug. 24, while over the city of Hull, England, the R38 broke apart in midair, exploded and crashed into an estuary, killing 44 of its crew of 49. Among the dead, according to Scot Christianson’s book, Cats in the Navy, was the R38’s all-black mascot kitty, Snowball, which had been taken to England as a good-luck charm.

Construction of the USS Shenandoah in 1923

The skeletal hull of the ZR-1 was made of Duralumin, a lightweight aluminum-copper alloy. More than 400,000 separate components were used to create the hull, which measured 680 feet in length and 78 feet, nine inches in diameter at its widest point, with an empty weight of more than 38 tons. (By comparison, the modern-day Goodyear blimp is barely a third as long at 246 feet.)

The frame was covered with tightly woven cotton and covered with several coats of “dope,” a cellulose nitrate-based lacquer frequently used in early aviation to tighten and weatherproof cloth. (The Wright brothers used dope to cover the cotton wings on the Wright Flyer.) The final coat of dope included an aluminum powder coating, which helped make the skin more weather-resistant and worked to reflect the heat of the sun.

The first iteration of the ZR-1 was powered by six 350-horsepower Packard engines, supplied by 40 fuel tanks with a total capacity of 4,424 gallons of gasoline. One of the engines was mounted at the rear of the control gondola. However, according to The Wreck of the Naval Airship USS Shenandoah by Jerry Copas, a hot-air balloon pilot with 50 years of experience, the engine behind the control gondola was later removed to make room for more radio and “direction-finding equipment.” (Packard frequently used images of the Shenandoah in its print advertising, as did Exide, a Philadelphia-based radio battery manufacturer.)

Because of the explosions of the R38 and Roma, Navy officials elected to use helium instead of hydrogen in the ZR1. Hydrogen is a plentiful gas, but highly flammable. (The most famous dirigible disaster in history was the 1937 explosion of the hydrogen-filled Hindenburg.) Helium is inert, but rare. The challenge for the Navy was finding the more than 2.1 million cubic feet of helium needed to fill the 20 gas cells that would keep the airship afloat. When that mission was completed, it had nearly drained the world’s helium reserves.

The gas cells were covered in goldbeater’s skin, which was made from the outer membrane of cow intestines and at the time was one of the most gas-impervious materials available. (According to Rayner, it took the intestines of 750,000 slaughtered cows to get enough membrane for the Shenandoah.)

When completed, the ZR-1 had a hefty 1923 price tag of $2.9 million, equivalent to more than $37 million in today’s dollars.

On Oct. 10, 1923, the ZR-1 was christened the U.S.S. Shenandoah by Marion Thurber Denby, the wife of Secretary of the Navy Edwin Denby. A Virginia native, Mrs. Denby reportedly named the airship after the Shenandoah Valley, where she had grown up. (Since the day it was dedicated, numerous publications have stated that Shenandoah is an Algonquian name that translates to “Beautiful Daughter of the Stars,” and the Shenandoah would carry the sobriquent Daughter of the Stars to its grave. However, a spokesperson for the Myaamia Center, a Miami Tribe of Oklahoma initiative located at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, said the name Shenandoah is not Algonquian, but a common Native American term that most likely originated with the Iroquoian-speaking tribes that made up the Six Nations.)

The christening took place at the height of Prohibition, so Mrs. Denby could not break a bottle of champagne against its hull, as was tradition. Instead, she pulled a ribbon, opening a cage containing three carrier pigeons, which delivered a message to President Calvin Coolidge announcing the Shenandoah’s entrance into the U.S. Navy Bureau of Aeronautics.

That month, the Shenandoah was flown to the Pulitzer Trophy Air Races in St. Louis. According to Copas’s book, the event featured in-formation flying, bombing demonstrations and racing. However, it was the arrival of the Daughter of the Stars that stole the show.

***

It may be difficult for modern Americans to understand just how important the Shenandoah was to the Navy and the people of the United States. Germany, who we had defeated in World War I, had for years been engineering and building magnificent airships. Our ventures with the R38 and the Roma had led to not only 78 deaths, but also embarrassing headlines.

And then the Shenandoah was released from its hangar – American-engineered, American-made, American-manned.

Despite the fanfare, the Shenandoah stuttered out of the blocks, too.

In December of 1923, just two months after the christening of the Shenandoah, Coolidge announced plans to send the airship on an exploratory mission to the North Pole the following year. However, those plans were scuttled when, on the evening of Jan. 16, 1924, the Shenandoah was ripped from her Lakehurst mooring tower by 72-mile-an-hour winds. According to an Associated Press report, the Shenandoah was swept “on a mad chase up the Atlantic coast to Staten Island, New York City.” The battered airship limped back to Lakehurst, its outer skin, nose cap and vertical fin all badly damaged.

The USS Shenandoah leaving the airship hanger at Naval Air Station n Lakehurst, New Jersey.

Instead of exploring the Arctic, the Shenandoah was docked in Lakehurst for repairs and modifications. It was during this time that Lansdowne made a decision that ultimately may have led to the Shenandoah’s catastrophic collapse. He wanted to remove 10 of the ship’s 18 gas release valves. The intent was to lower the weight of the Shenandoah and save valuable helium. While the move may have looked good on paper, it also meant the airship would be unable to release helium quickly in an emergency if the ship was ever caught in an updraft and needed to reduce its buoyancy.

It would take eight months to get permission to remove the valves.

According to Item 25 in the official court of inquiry, reprinted on the U.S. Naval Institute website, Lansdowne began his efforts to have the gas release values removed on Sept. 16, 1924, when he sent a letter requesting “certain changes in the system of gas valves” in the Shenandoah.

Three weeks later, the Shenandoah left Lakehurst on Oct. 7, 1924, to begin its 9,000-mile cross-country journey, the longest trip ever by an airship. It was ostensibly to test docking stations, but it was as much a public relations tour as anything. National Geographic Magazine chronicled the trip in its January 1925 issue. The magazine dedicated 47 pages to the trip as writer Junius B. Wood traveled aboard the Shenandoah.

The story began under the headlines: “SEEING AMERICAN FROM THE ‘SHENANDOAH’ – An Account of the Record-making 9,000-mile Flight from the Atlantic to the Pacific Coast and Return in the Navy’s American-built, American-manned Airship”.

As the Shenandoah reached Dayton, Ohio, instead of immediately turning southwest to cut across Indiana, Lansdowne steered the craft northwest 32 miles to fly over his hometown of Greenville, Ohio, where his wife and mother were living.

At the conclusion of the historic trip, the Shenandoah became the most famous aircraft in the United States and Lansdowne arguably its most famous aviator, with the possible exception of fellow Ohioan and World War I fighter ace Eddie Rickenbacker. Lansdowne was to 1920s aviation what John Glenn and Neil Armstrong, also Ohioans, would be to the space program.

After the cross-country flight, everyone knew of Zachary Lansdowne. According to granddaughter Hunt, when Lansdowne returned to Greenville in November of 1924 to visit his mother over the Thanksgiving holiday, a throng of people met him at the train station and he was presented with a gold watch. A Nov. 23, 1924, article in the Greenville Daily News Tribune told of a reception held in his honor. The article stated that Lansdowne had brought “international fame to our little city.” The paper covered the brief visit with four separate articles.

When he returned to Lakehurst after the homecoming, Lansdowne renewed his efforts to have the gas release valves removed. He made the recommendations in letters dated Dec. 15, 1924; Jan. 9, 1925 and May 12, 1925, and in a telephone conversation on May 28, 1925. With the blessing of the commanding officer of the Naval Air Station Lakehurst, the Navy Bureau of Aeronautics approved the reduction in automatic valves on an experimental basis on May 28, the same day as the telephone conversation. The valves would remain on cells 4, 5, 8, 9, 12, 13, 16 and 17.

***

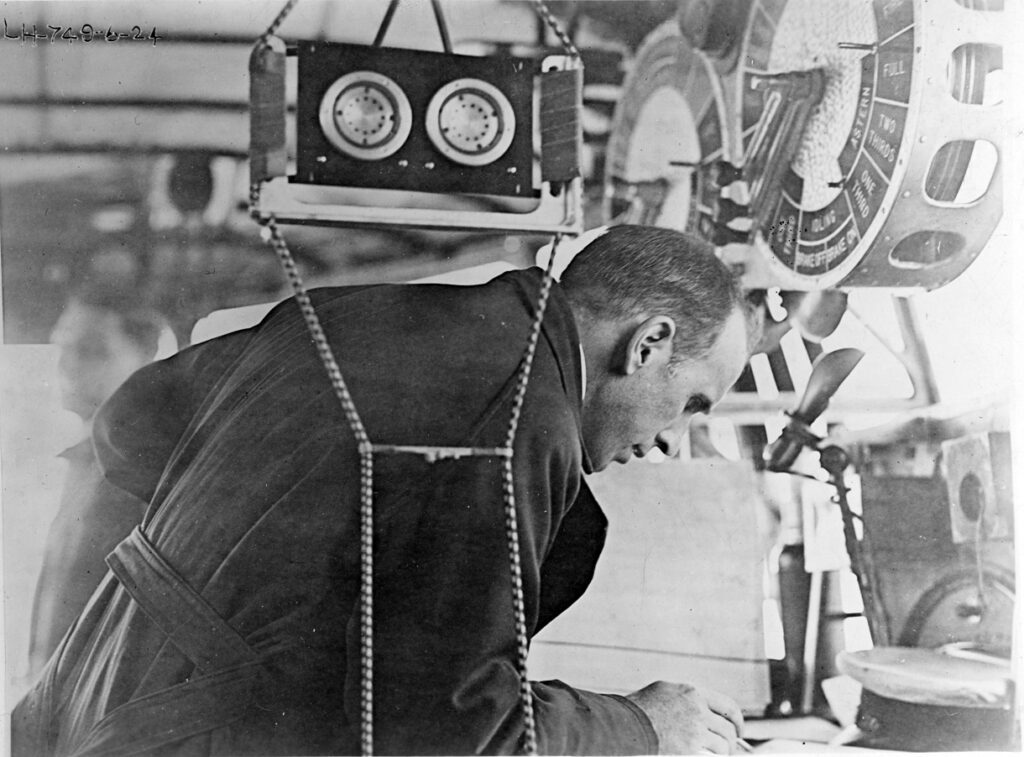

Lt. Cmdr. Zachary Lansdowne

Zachary Lansdowne was born on Dec. 1, 1888, in the western Ohio village of Greenville, which is best known as the site of the 1795 Treaty of Greene Ville, which followed Gen. Mad Anthony Wayne’s defeat of the Shawnee and Miami at the Battle of Fallen Timbers. The treaty ended four decades of hostilities between Native Americans and settlers and opened Ohio for westward settlement and statehood in 1803.

Lansdowne was the youngest of three boys born to James and Elizabeth Knox Lansdowne, a prominent Greenville family. His father died when he was 10 and two older brothers served as his role models. According to Hunt, Lansdowne was more bookish than athletic. He excelled in math and art, and was popular at parties for his piano skills.

He accepted an appointment to the United States Naval Academy during his junior year in high school. He elected to forgo his senior year at Greenville High School and enrolled in the academy as a 16-year-old in September of 1905.

He graduated from Annapolis in 1909 and became a Navy recruiting officer based in Cleveland, Ohio. He married Ellen MacKinnon of Wisconsin, and they had a son, Falkland MacKinnon Lansdowne, who was born in 1915. According to Hunt, on the evening of June 22, 1916, the Lansdownes went out for the evening when Ellen said she wasn’t feeling well. They returned home, and she was dead the next day. Hunt speculated that she may have died of food poisoning.

Their son, who Hunt knew as “Uncle Mac,” was raised largely by Ellen MacKinnon’s family in Wisconsin while his father was on duty and after he was orphaned at the age of 10.

After leaving his assignment in Cleveland, Lansdowne went to Pensacola, Fla., to begin flight instruction, and in August 1917, he began lighter-than-air training in Akron, Ohio. He was receiving additional dirigible training in England when the United States entered World War I and was assigned to command the U.S. Naval Aviation Base in France.

He later became the first American to cross the Atlantic Ocean in an airship when he accompanied the British dirigible R34 on a 108-hour trip in 1919, for which he was awarded the Navy Cross and England’s Air Force Cross.

Hunt said Lansdowne later became a naval attaché in Washington, D.C. Margaret “Betsy” Lansdowne had gone to work for J. Edgar Hoover at the FBI at the age of 19. Hunt said they met at a White House event and were married on Dec. 7, 1921, after a “fairly short romance.” They would have one daughter, Peggy.

When Lansdowne was made commander of the Shenandoah, the Feb. 12, 1924, issue of the Greenville Daily News Tribune ran an article under a headline that read, in part:

LOCAL BOY MAKES GREAT ADVANCEMENT

Lieut. Zach Lansdowne, a native son of Greenville, has been accorded the honor of commanding the largest airship afloat, the U.S.S. Shenandoah.

While he may have been one of the world’s most famous aviators, he is not the best-known person to come out of Greenville. The undisputed claimant of that title is Annie Oakley, who gained fame in the 1800s as Little Miss Sure Shot while performing for William “Buffalo Bill” Cody in his Wild West shows and was, according to a PBS documentary, “the first American woman ever to become a superstar.” The Garst Museum in Greenville has impressive displays for the Treaty of Greene Ville and Oakley . . . but mostly Oakley.

In fact, Lansdowne’s local fame is a distant third behind Oakley and legendary broadcaster, filmmaker and journalist Lowell Thomas, who was born in the Darke County hamlet of Woodington. Thomas is credited with creating a travelogue that brought the exploits of Col. T.E. Lawrence, a k a, Lawrence of Arabia, to the theaters of America. He would later pen the book With Lawrence of Arabia.

At the height of the Roaring Twenties, Zachary Lansdowne was a household name. Not so today. But isn’t it the cyclical nature of history that names fade with the years? Lansdowne’s bronze-medal placement on the pantheon of Darke County celebrities didn’t sit well with the late Florence Hoblit Magoto, and it launched a bit of a war between the Garst Museum.

Magoto died in 2016, but both Rayner and Hunt had interactions with her. Magoto’s family purchased the Lansdowne house after the death of his mother. Rayner said Magoto had a strong personality and complained long and loudly that Lansdowne didn’t get his due in his hometown, finding it unfathomable that a 19th century trick-shot artist could be better-known and revered than a decorated Navy aviator.

Magoto worked to get Lansdowne’s house on the National Register of Historic Places and donated a monument to his memory that sits on the grounds of the museum. In a biography that Magoto wrote of Lansdowne, which is on file at the Garst Museum, she stated, “His memory is all but forgotten.” On the 75th anniversary of the crash, Magoto told the Dayton Daily News, “No one in this town had ever done anything to remember Lansdowne. So, I bought this stone and had it inscribed.”

While Hunt believes more could be done to preserve the memory of her grandfather, she never appreciated Magoto’s methods. Hunt went to Greenville for the dedication of the monument and sat in the audience as Magoto attacked the officials from the Garst Museum for not doing more to recognize Lansdowne.

“I think it’s a shame that Annie Oakley gets all the attention, but that was no reason for Florence to start a war with the Garst Museum,” Hunt said. “There was no call for that. We were there for the ceremony, and she called out the people from the museum. It was really embarrassing. I always felt that Florence was in it for herself. She wanted credit for everything and liked to see her name in the paper. She really rubbed me the wrong way.”

***

While most of Noble County slept, C.L. Arthur of Belle Valley was up early on Sept. 3. It had been well-publicized that the Shenandoah would be making its way across Ohio that morning on its public relations tour. Arthur would tell the International News Service that he and a few other locals were outside in anticipation of the airship’s arrival in the eastern sky.

“It was just after dawn and the few of us who were up were watching the airship as it came into view over the rim of the mountains,” Arthur said. “It was a beautiful thing as it glided through the sky and we stood there, almost overawed by the thing as it came on toward the spot where we were standing.”

While it may have appeared to Arthur that the Shenandoah was gracefully gliding through the sky, that certainly wasn’t the reality at 3,000 feet. It had been fighting the wind for hours, traveling westward, just south of present-day Interstate 70. At 4:55 a.m., the radio operator reported that Pleasant City was in the distance. It’s a little over 78 miles from Wheeling to Pleasant City, as the crow flies. The Shenandoah was capable of 70 miles an hour in good weather. After passing Wheeling, the airship averaged just 26 miles an hour as it battled the elements.

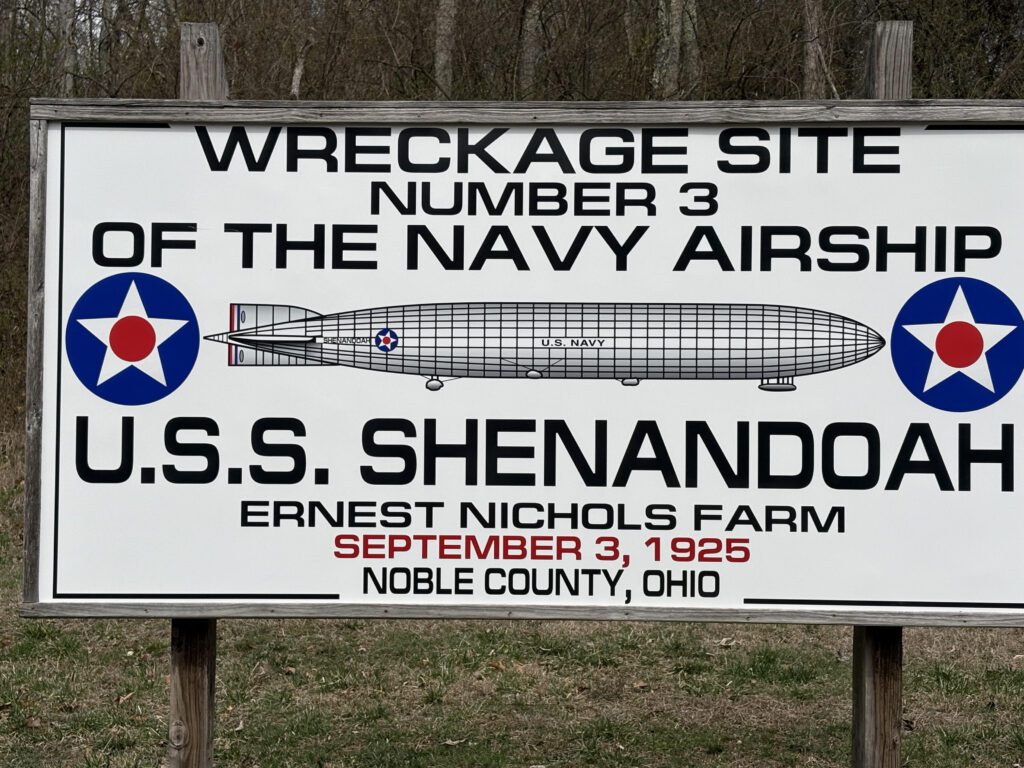

Sign marking the wreckage site in Noble County, Ohio.

“I’m a hot-air balloon pilot, and I have more information on my cell phone than they had in that airship,” Copas said. “I can check my phone and decide if I can go up. Those guys on the Shenandoah didn’t have a clue what they were flying into.”

The winds were battering the Shenandoah and, if the crew had any control, it

wasn’t much. Because Lansdowne had ordered the removal of the 10 gas-release valves, the Shenandoah could not jettison helium fast enough to help in the recovery. According to the Time magazine article, 16 men had occupied the gondola when Lansdowne ordered Lt. Cmdr. Charles E. Rosendahl, the Shenandoah’s navigator, into the hull to dump fuel to drop weight. It was a move that would save Rosendahl’s life.

Col. Chalmers G. Hall was an Army observer aboard the Shenandoah. In a story in the Sept. 3 edition of the Columbus Evening Dispatch, Hall said the airship had dodged the bad weather by changing course “a dozen or more times” before hitting what he described as a line squall. Hall told reporters that the storm “sent us to an altitude of 5,500 feet before we realized what had happened.” While Lansdowne remained at his post, Hall announced in the command gondola, “Everyone beat it.”

The only route from the gondola to the hull of the airship was through a hatch in the roof and an open ladder, which is how Hall elected to get there. Following him up the ladder was Lt. Joseph B. Anderson.

As the airship was suddenly thrust high into the air, Arthur watched from the streets of Ava. He told the Evening Dispatch, “Then suddenly there was a roar that resounded over the countryside and the giant bag split.”

The Shenandoah had been torn in two about 200 feet behind the nose.

According to excerpts of an American Heritage magazine article that appeared in the May 31, 1959, issue of the Washington Post and Times Herald, the Shenandoah “began turning rapidly in a circle. The tail was suddenly thrown up and wrenched to the right. Suddenly, there was a shrill screech as girders began to twist and tear.”

One theory for the cause of the crash is that the Shenandoah’s gas cells swelled as the helium expanded. Unable to release the excess helium, it pushed out on the girders and ruptured the skeleton, splitting the hull in two. When the airship split, the cables that tethered the gondola to the hull broke from their moorings and screamed through the hull. Imagine the gondola as an angry marlin and the line coming off a fishing reel as the cables. The Time article described it: “Like a breast pin torn from a satin gown, the great control cabin was ripped from the body of the ship.”

According to a report on the National Air and Space Museum website, Lt. Thomas B. Hendley wrote that the Shenandoah rose to an altitude of 7,000 feet and broke in two after hitting a current of cold air. Several witnesses reported seeing the Shenandoah rise and fall several times. After it broke in two, the witnesses said the torn ends of the bow and stern pointed upward.

At this point, there were 14 men inside the control center. According to Theresa Rayner, Lansdowne had told the remaining men they were free to escape to the hull. None left. Whether they did so out of a sense of duty or the turbulent conditions prevented them from escaping will never be known.

Meanwhile, Hall and Anderson were still making their way up the ladder toward the hull.

“When the crash came, I was on the ladder leading from the control cabin to the rear portion of the ship,” Hall said. “As I started to fall, I clutched a girder.” He said he was able to swing his body over the girder and crawl “40 to 50 feet back into the ship.” As he made his way into the broken stern, Hall found Lt. Roland G. Mayer and Anderson opening the gas cell release valves, bleeding off the helium to allow the massive stern to settle to earth. The stern began a quick glide down, due in part to the weight of the three Packard engines still attached to the hull.

Arthur said, “Even after it was chopped in two, this main part of the ship, it seemed to stay up there motionless for some time, then gradually sink toward the earth.”

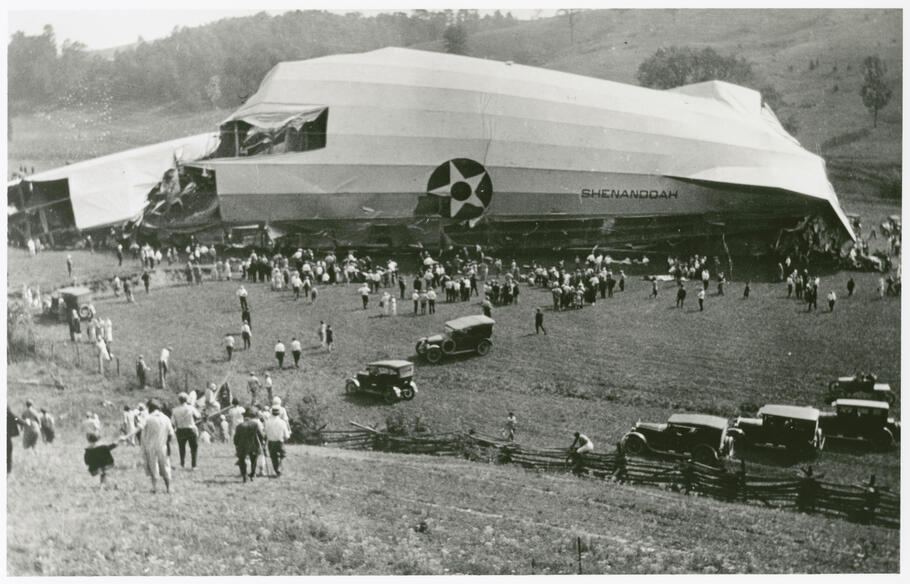

The stern floated west less than a mile, quickly losing altitude with 22 men hanging on to ladders and ropes, before sliding into a farm field owned by the Charles Niswonger, just west of present-day Interstate 77. It came to rest on its belly, the boldly lettered SHENANDOAH and the starred emblem of the Navy Bureau of Aeronautics clearly visible.

Today, the spot is marked with a sign and flagpole and can be seen clearly from the interstate, near mile marker 32.

Anderson was closer to the gondola when the ship split. He also grabbed a girder and swung clear of the falling control center. Anderson would tell investigators that he looked down and was hanging over the massive hole created by the fallen gondola. According to the American Heritage article, “The next thing he knew he was sitting on a fragment of the catwalk, suspended directly over the center of the jagged hole.”

In a Sept. 5, 1925, article in the New York Times, Anderson was quoted as saying, “The whole ship was full of groans and noises. Then came the crash as she snapped in two. That was just after I got out of the control car and was going up the ladder to the catwalk. I had hardly reached the platform when the control car snapped and dropped straight down into space.”

Andy Gamary, a coal miner from Belle Valley, had just gotten out of bed and was heading downstairs. According to a story by Robert French in the Sept. 4 issue of the Evening Dispatch, Gamary’s “squat, barefooted wife” had made coffee and called him to breakfast when they heard “a crash that rocked the house.”

According to the article, Gamary ran to the door, “just in time to see a gigantic monster whirling and swirling about in midair, hovering over the houses like a mythical Roc of the Arabian Nights.”

(In the tale of The Arabian Nights, the roc is a giant bird of prey, large and strong enough to carry off an elephant.)

Gamary was watching the 480-foot stern section as it made its way to earth. The crash he had heard was the gondola being crushed onto the ground of his farm, not far from the house. Gamary, according to the article, had no knowledge of the Shenandoah and its trip over the area, and the scene was difficult for him to comprehend. What was easy to comprehend were the three battered bodies on his property. He saddled up his horse and rode for a doctor, perhaps not realizing that the men in his yard and those in what remained of the gondola were all well beyond the help of any doctor.

Ten members of the crew were found in the wreckage of the gondola. Four others had somehow dislodged from the command center and were found nearby.

With seven men inside the lighter nose of the ship, it continued floating southwest. The crew reportedly attempted to bleed off the helium to get the wreckage to the ground, without success. The nose had floated about eight miles, and members of the crew were dropping ropes in hopes of snagging something that would stop the drift, when they spotted Ernest Nichols walking across his farm near the community of Sharon. Nichols was unaware of the disaster until he heard men calling to him. He turned to see the bow of the Shenandoah floating above his farm. Nichols grabbed a dangling rope and tied it to a tree.

According to the Time article, Chief Machinist Shine S. Halliburton had fired shots into the gas cells, which helped to lower the nose. If that was the case, why was it still floating eight miles from where it split up? Nichols long maintained that after he tied up the bow, at the direction of the men inside, he ran into the house, returned with his shotgun and fired two blasts into the gas cells, allowing the bow to sink to the ground.

One of the men in the bow was Rosendahl, the most senior officer to survive the crash. He would later rise to the rank of rear admiral and return to Noble County in 1971 to visit with Nichols. Rayner has photos of Nichols and Rosendahl in her collection, along with a photo of Nichols posing with his shotgun. Included in her museum are two spent shotgun shells, given to her by Nichols’ son, Stanley, that were supposedly from the two blasts into the gas cells.

When the sun set on Sept. 3, 14 men were dead. Twenty-nine survived – seven in the bow and 22 in the stern.

***

Fourteen wooden caskets were laid out on the sidewalk in front of Dye’s Funeral Parlor in Belle Valley. The local American Legion scrambled to find 14 American flags to drape over the caskets. Rayner has a photograph of men sitting on the caskets like they were park benches, enjoying a smoke. The remains were later transferred to the train station in Cambridge for their final ride home.

A mere four days after the crash of the Shenandoah, on Sept. 7, 1925, Lt. Cmdr. Zachary Lansdowne was laid to rest with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery. He would later be joined there by three of his Shenandoah comrades.

In an article in the Greenville Daily Advocate on the afternoon of the crash, Lansdowne’s mother said she had recently received a letter from her son in which he said the tour would be his last on the Shenandoah and that afterward he was to report for sea duty.

This would have made her happy because she didn’t want her son to fly in the first place. According to Hunt, Lansdowne’s mother, Elizabeth, placed the blame for his death not on the wind or structural failure, but on the shoulders of his wife.

“His mother and Ellen MacKinnon didn’t want him to fly,” Hunt said. “He married Betsy and she encouraged him to fly. After the accident, his mother blamed Betsy for his death. She said, ‘You encouraged him and therefore you killed him.’ Things didn’t go well for her and Lansdowne’s mother after that.”

The feud wouldn’t last long. Five weeks after her son was killed, Elizabeth Lansdowne died at age 74. An Associated Press article of Oct. 10, 1925, stated that she had been in ill health for several years and her death was attributed to “heart affection and shock occasioned by her son’s tragic death.”

(Betsy Lansdowne was remarried in 1927 to John Caswell Jr. She became the long-time women’s editor of the Washington Star. She died in 1982 at the age of 79.)

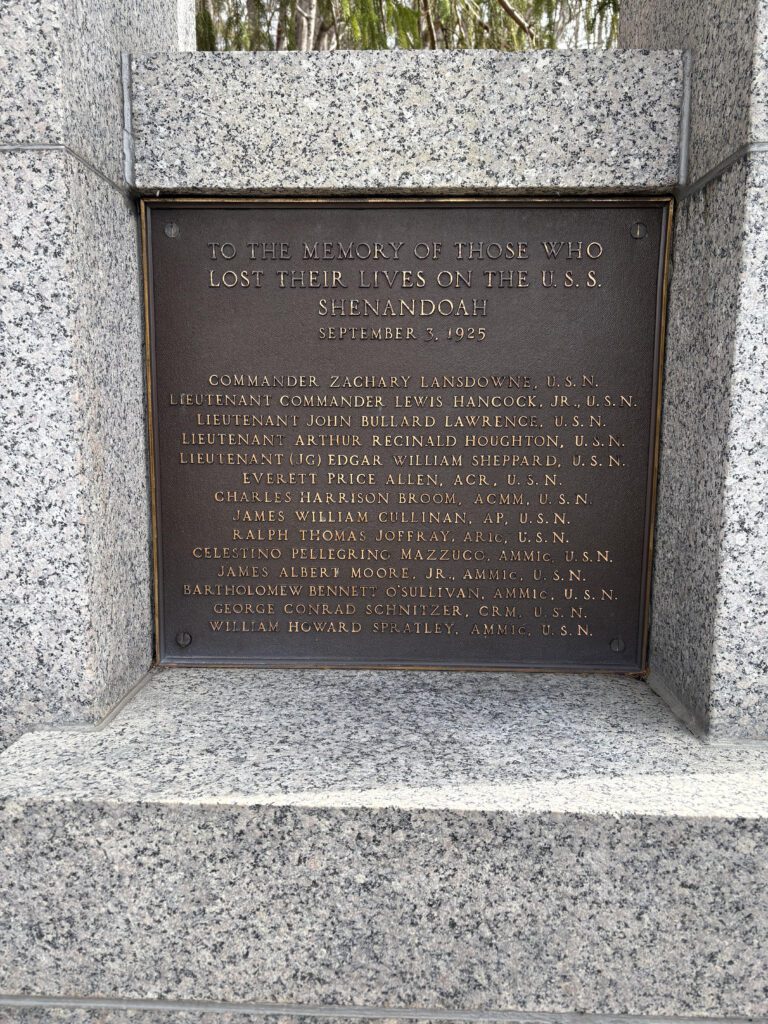

Memorial plaque dedicated to the lives lost from the U.S.S. Shenandoah crash

Monument Dedicated to Lt. Cmdr. Zachary Lansdowne at the Garst Museum in his hometown of Greenville, Ohio

A week after his death, Lansdowne’s portrait graced the cover of the Sept. 14, 1925, issue of Time magazine with the caption, “The Late Zachary Lansdowne.” The magazine described him as “gallant” and “air-tested.”

He would be posthumously honored by the Navy, which named a Gleaves-class destroyer the U.S.S. Lansdowne.

Who was to blame for the crash of the Shenandoah? Did the Navy take unnecessary risks by flying into the Midwest at the height of storm season for the sake of public relations? Absolutely. Did Lansdowne deserve some of the blame for removing the 10 gas-release valves from the airship? Probably.

In newspaper reports within days of the accident, Lansdowne’s wife placed the blame for her husband’s death on the Navy, which she said was more concerned about the public relations value of the flight than the lives of the men inside. She said, “Commander Lansdowne was very much opposed to making the flight at this time, and he advised the department accordingly. Having been born in the Ohio Valley, knew weather conditions out there and had some fear of them.”

The American Heritage article stated that at the Navy inquest, the 23-year-old maintained her assertion that she had become a widow for the Navy’s political purposes. When naval officers pressed her to recant her earlier criticism and showed her the clause in his orders that allowed her husband to delay the trip if he felt it was dangerous, she pointed to the conclusion of the clause, which read, “remembering, however, that this route will be published in the press, and that many will be disappointed should the Shenandoah fail to follow the approved schedule.”

Mrs. Lansdowne said, “That is the pressure that is brought on officers in the Navy Department.”

Secretary of the Navy Curtis D. Wilbur countered, releasing a statement that read, “Captain Lansdowne fixed his own time for making the flight into the Middle West, and was also given absolute discretion as to the route to be followed going and coming. He did not think the flight should be made during the months of July and August. His wish to defer the voyage from July to September was complied with by the department.”

However, documentation appears to show otherwise.

On June 15, 1925, Lansdowne sent a letter to Adm. Edward Walter Eberle, chief of Naval Operations, suggesting the tour be delayed. According to airship.net, “Eberle was unmoved.” Lansdowne appealed to Rear Adm. William A. Moffett, the chief of the Navy Bureau of Aeronautics, who granted the commander a slight delay until early September. When Lansdowne again wrote to Eberle asking for a further delay, Eberle wrote in an Aug. 12, 1925, letter, “Your recommendation to make the flight the second week of September has not been approved.”

Author Copas puts the blame for the crash on that decision.

“Plain and simple, it was a misuse of a naval asset, and it shouldn’t have been where it was,” Copas said. “The Shenandoah was designed to be a high-altitude observation platform to support the fleet, and that’s why the program was given to the Navy. I’ll tell you what the Shenandoah wasn’t designed for: flying on a public relations tour through the Midwest at the height of storm season. It wasn’t constructed to take that kind of a beating.”

Multiple sources cite Lansdowne’s decision to reduce the number of gas-release valves as a possible reason for the crash

Capt. Anton Heinen, a German dirigible expert who served as an advisor during the construction of the Shenandoah, placed the blame squarely on Lansdowne. Reacting to the fact that he had ordered the removal of the valves, Heinen said in Time magazine, “I would not call it murder, but I cannot put it too strong that if it had not been for the foolishness in cutting down the number of safety valves, the crash would not have occurred.”

In an article in the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, Heinen said the elimination of the valves was the cause of the crash as the expanding helium cells crushed the Duralumin frame. In a later article in the Washington Post and Times Herald, he was quoted as saying, “The victims gave their lives to save precious helium.”

The article in the National Geographic, published nine months before the crash, backs up Heinen’s claims. Under the headline, “HELIUM IS TOO EXPENSIVE TO RELEASE FREQUENTLY,” the article states, “As the noncombustible helium gas which the Navy uses costs $55 or more per 1,000 cubic feet, valving is frowned on. With the dangerous, but inexpensive, hydrogen, landing can be made almost at will. Similar liberal valving of helium would cost from $5,000 to $20,000 for each landing.”

The gas cells on the Shenandoah were filled to 85 percent capacity, which allowed room for the gas to expand in higher altitudes. According to the article in the National Geographic, at 4,500 feet, the bags are at 100 percent capacity. In Hendley’s report on the National Air and Space Museum website, the Shenandoah climbed to 7,000 feet, or 2,500 feet above where the gas cells were at capacity, which could have created enough internal pressure to fracture the frame.

If the storm was largely to blame, how did it bring down the massive Shenandoah? The original 1925 report of the crash quoted several sources who claimed the Shenandoah was a victim of a line squall. However, Andrew Buck Michael, a meteorologist for ABC6/Fox 28 in Columbus, Ohio, said the proper meteorological term for such an event is the inverse – squall line.

Michael studied the weather report and photos of the hills surrounding the crash site to determine if it was, indeed, a squall line, in which the front edge of a storm creates a giant vacuum and updraft.

“I went back and forth on this, but I think they had it right when they determined the Shenandoah was the victim of a squall line,” Michael said. “I initially thought a supercell thunderstorm would make more sense with the violent winds, but after more research, a squall line does seem more likely to have caused the violent shift in the airship’s altitude.”

Squall lines are thunderstorms, typically extending north to south, that can produce 80-mph wind gusts, hail and, at times, tornadoes.

“A squall line has a lot of lift in the atmosphere on the leading edge with winds racing up,” Michael said. “That is quickly followed by downward winds. The nose of the Shenandoah was reportedly pushed upward, heading into the heart of the storm. Since the airship was 680 feet long, the nose was initially caught in the lift, which caused it to point upward. As it continued into the storm, the nose moved into the downdraft while the stern was still in the updraft. You have a wall of wind blowing up and a wall of wind coming down, and the Shenandoah was caught in the middle. I can’t overstate how powerful this would be. Obviously, powerful enough to tear the Shenandoah in two. I wish we had more data, like radar, back in 1925.”

A Naval Board of Inquiry said that when the gondola was ripped from the hull, it created holes in the skin of the hull. The air rushing through those holes caused the Shenandoah to break in two. The wrenching of the cables was caused by the “rolling and rising and falling in the wind.” The Naval Board of Inquiry believed the hole from the gondola led to the structure failure, but those on board said the opposite, that the structure failure allowed the cables supporting the gondola to tear loose.

Science always demands an explanation. It was a faulty, rubber O-ring seal that brought down the Challenger. The Columbia disintegrated because a piece of foam dislodged from an external fuel tank during takeoff and damaged the ship’s thermal protection system. But we simply didn’t have the necessary science in 1925 to provide a definitive reason for the break-up of the Shenandoah.

There are many opinions as to why the airship crashed. Perhaps it was simply the inherent danger of sending a giant, gas-filled balloon into the unpredictable eastern Ohio sky. The odds favor the elements and on that day, as Lansdowne had feared, they had the upper hand. Why would anyone think otherwise? After all, the list of spectacular failures – the R38, the Roma, the Hindenburg – far outweighed the successes. And perhaps it was, so to speak, a perfect storm of arrogance, carelessness, wind and structural weakness.

Looking in the rearview mirror at ten decades past, it’s still a worthy question to wonder why the Navy was so obsessed with building the airship. From a military perspective, it would seem to have had little value. Even if the airship had been used for surveillance, was the plan to send a lumbering bag of gas more than an eighth of a mile in length into battle?

What could possibly go wrong?

But the race for superior airships was the moon race of its day. The Germans had a giant head start and the United States was not to be denied.

The Navy had a total of four dirigibles in its fleet – the Shenandoah and her sister ship, the U.S.S. Los Angeles; the U.S.S. Akron and her sister ship, the U.S.S. Macon.

On April 3, 1933, The Akron encountered a storm off the New Jersey coast and crashed tail-first into the Atlantic Ocean, killing all but three of a crew of 76. During the rescue, the Navy sent the non-rigid airship, J-3, to look for survivors. It also crashed, killing two men. Six of the men killed on the Akron were survivors of the Shenandoah disaster. Also killed was William A. Moffett, who had granted Lansdowne a slight a delay in the fatal tour.

On Feb. 12, 1935, the Macon was concluding a test run and returning to Moffett Field in Santa Clara County, Calif., when it ran into a storm near Point Sur. The wind tore off the Macon’s upper fin and the airship crashed into the Pacific Ocean, killing two crewmen.

The Los Angeles was in service from 1924 to 1932 and was the only airship to reach retirement without crashing. It should be noted that the Los Angeles was constructed by Luftschiffbau Zeppelin and purchased by the United States.

The wreck of the Shenandoah also launched one of the most high-profile court-martials in United States history. In the days following the disaster, Col. William “Billy” Mitchell publicly accused the leadership of the Army and Navy of incompetence. He was convicted of insubordination and suspended from duty for five years. He elected to resign.

“Before the flight, Lansdowne confided in Billy Mitchell that he was upset that he was being sent on this tour of state fairs,” Copas said. “When his buddy Lansdowne was killed, that’s when Mitchell went public and ended up with his court-martial.”

His story was the subject of a 1955 movie, “The Court-Martial of Billy Mitchell,” starring Gary Cooper as Mitchell, Jack Lord of “Hawaii Five-O” fame as Lansdowne, and Elizabeth Montgomery, TV’s “Bewitched”, as Lansdowne’s widow.

***

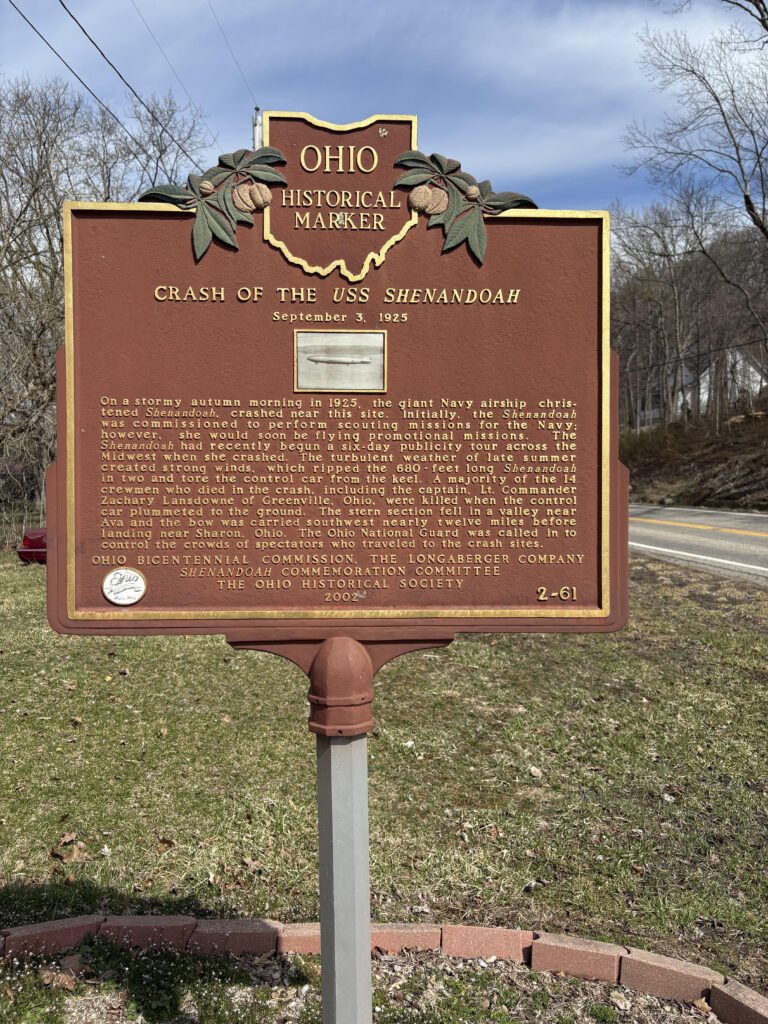

Ohio Historical Marker commemorating the U.S.S. Shenandoah

In 1961, four tiny, rural school districts in Noble County – Batesville, Belle Valley, Sarahsville and Summerfield – consolidated to form the Noble Local School District. In the fall of 1963, Shenandoah High School opened on Zep Road East in Sarahsville with the nickname Zeppelins, which over the years has been shortened to Zeps.

A guy who knows the history of the area well is the district’s current superintendent, Justin Denius, who grew up in Ava and every day passed the two Shenandoah markers that sit on Rt. 821. One is a memorial erected by the federal government in 1937 to honor the men who perished in the Shenandoah. The other is a state of Ohio historic marker commemorating the crash. It sits in the parking lot of the old Rayner Service & Towing location, which Theresa closed after her husband died.

Denius went to Shenandoah High, played on the football team and graduated in 1992. After earning his bachelor’s degree from nearby Marietta College, he returned to his alma mater – where his father once taught industrial arts – as a teacher, principal and, now, superintendent.

On the wall of his office is a photo of the fallen stern of the Shenandoah. He is quick to point out that it’s an original that belonged to his grandmother and not a reproduction.

Quite simply, Denius is a hometown boy and proud of his roots. He wants the students in his school district to have the same appreciation for the Appalachian hills in which the schools sit and the history of Noble County. The high school is adding a new wing with a 100-foot main corridor. Built into the ceiling of the corridor will be a one-seventh scale replica of the bottom of the Shenandoah, along with 14 clouds, one each for the men who perished in the accident. Along the walls will be storyboards detailing the events of Sept. 3, 1925.

“I want our students to be proud of where they came from and remember the historical events that are important in Noble County, and the Shenandoah is at the top of that list,” Denius said. “We don’t have a specific curriculum item that studies the Shenandoah, but trust me, I don’t miss an opportunity to talk about it, and our teachers incorporate the story where it makes sense. The Shenandoah is our namesake and it’s important that the kids know that.”

(Technically, the U.S.S. Shenandoah was not a Zeppelin, but a lighter-than-air rigid airship. Only airships built by Luftschiffbau Zeppelin carry that designation. Zeppelin, however, became the colloquial name for all such airships, much the way Jacuzzi is used for hot tubs. In defense of the Noble Local School District officials who made that decision, the Shenandoah High School Fighting Lighter-Than-Air Rigid Airships simply doesn’t have the same ring as Zeps. And they weren’t the only ones who got it wrong. Before its christening, the Navy named the airship ZR-1, which stood for Zeppelin Rigid.)

Much has changed in Noble County in the past 100 years. On that fateful day, the county was dotted with many small towns and commerce that grew up around the coal mines that honeycombed these Appalachian hills. The vast majority of Noble County was farmland and mining communities connected by dirt roads and beaten paths. Today, Interstate 77 – U.S.S. Shenandoah Memorial Highway – bisects Noble County, giving a distorted view of how the events of Sept. 3, 1925, unfolded. After the gondola fell, the stern slipped over hills and dales; it did not float over Interstate 77.

On the morning of Aug. 31, a commemoration will be held to mark the 100th anniversary of the wreck of the mighty U.S.S. Shenandoah. Theresa Rayner plans to take her traveling museum to the event. Lansdowne’s granddaughter has been invited to attend, and there will be the usual assortment of elected officials and local dignitaries, along with the pride of Shenandoah High School – the Marching Zeps.

Hunt said she appreciates the effort of Noble Countians in keeping the memory of her grandfather alive. She plans to attend the ceremony and notes it will probably be her last visit to the hills where he died. “There’s not going to be a ceremony for the 105th anniversary,” she said. “This one’s important.”

Rayner loves the Shenandoah and still frequently speaks to civic organizations and schools. But since her husband died, the responsibility for the museum has fallen completely on her. She doesn’t have a pickup truck and must rely on friends for a tow. As we slide into the second hundred years since the crash, she worries that people will forget and students will not know their heritage and their connection to the airship.

And the museum isn’t her only responsibility. The spot where the gondola fell is on property that has been in the family since it was purchased by her late husband’s grandfather. The county helps maintain the site, which contains a flower bed, a granite monument erected on the 50th anniversary of the crash in 1975, an American flag and a flat stone, etched with a chisel by a local man – no one remembers his identity – who was at the scene after the gondola fell. It reads: This is the spot of the Landowne (sic). It reportedly denotes the exact location where Lansdowne’s body was found.

Was it really? Rayner shrugs. “If it wasn’t, it was very close to there.”

While Rayner silently frets that kids may forget their connection to the Shenandoah, she needn’t fret too much as long as Denius is at the helm of the Noble Local School District. The school board recently purchased 44 acres of land across the road from the high school where they plan to build a new baseball field.

Part of Denius’ long-term plan for the property is the construction of a community building that will include not only a museum that honors the four schools that merged to create Shenandoah High School, but also a major display of the airship. He smiles and says, “If we can put it all together, I’m hoping we can get Theresa to donate her museum.”

Would she consider it? It’s a definite maybe.

“I’m not ready to give it up,” she said. “Maybe sometime down the road, if none of my grandchildren are interested in taking it over. My grandson says he’s interested, but he’s only eight. There might come a time when cars and girls are of more interest to him than the Shenandoah.”

###