Wandering the Stacks and What We Found There

Part 1 of a series that delves into interesting texts found in the Ohio History Connection's Archives & Library

By Emily Platt Benua

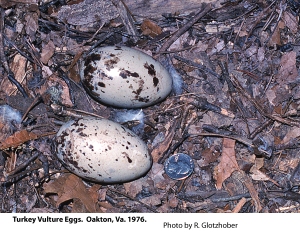

Living in the hills south of Lancaster, Ohio, and, at age 73, still able to climb them, I am interested in all the natural history of my area, plants and animals. My eyes and ears, however, are no longer sharp enough to observe I detail many of the birds of the area. But last summer I took up the study of a raptor, a silent variety which can only make a hissing sound the turkey vulture or buzzard. On May 6, I was showing a young man some of our large sandstone rocks, fun for climbing or for playing hide-and-seek. By chance I mentioned that this was the type of place where one might discover a buzzard nest. Id hardly spoken when he pointed under a rock; and there, on the ground in a slight hollow and well hidden were two eggs. He had found a nest!  The eggs were larger than a hens, dull white with brown blotches, a camouflage which more or less matched the ground and leaves in their hidden cave. No parent birds were in sight. I peeked at the nest twice after that, finding neither parent, and decided that the nest had been deserted. Sometime later Mr. Edward Hutchins, the head of Metropolitan Parks in Columbus, Dr. Edward Thomas, the well known naturalist of Columbus, and Dr. Carl Albrecht, the former curator of natural history at the Ohio Historical Museum, came down to our hills to breathe some clean, fresh air and study nature. My husband, Ben, showed them our Winnowing Rock, where years ago farmers took their grain for winnowing a flat rock on top of a high hill where the wind could blow away the chaff. I offered the buzzard eggs to Carl, who was delighted, so off we went in Bens jeep, two or three miles in the opposite direction, to the deserted nest. But there, for the first time, was a mother or father bird, sitting on the eggs. We all backed up. Carl didnt get his eggs, and I watched the nest the rest of the summer.

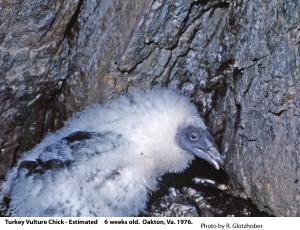

The eggs were larger than a hens, dull white with brown blotches, a camouflage which more or less matched the ground and leaves in their hidden cave. No parent birds were in sight. I peeked at the nest twice after that, finding neither parent, and decided that the nest had been deserted. Sometime later Mr. Edward Hutchins, the head of Metropolitan Parks in Columbus, Dr. Edward Thomas, the well known naturalist of Columbus, and Dr. Carl Albrecht, the former curator of natural history at the Ohio Historical Museum, came down to our hills to breathe some clean, fresh air and study nature. My husband, Ben, showed them our Winnowing Rock, where years ago farmers took their grain for winnowing a flat rock on top of a high hill where the wind could blow away the chaff. I offered the buzzard eggs to Carl, who was delighted, so off we went in Bens jeep, two or three miles in the opposite direction, to the deserted nest. But there, for the first time, was a mother or father bird, sitting on the eggs. We all backed up. Carl didnt get his eggs, and I watched the nest the rest of the summer.  The first baby hatched on June 8, a scrawny little thing almost bare even of its covering of white down. It couldnt stand and couldnt even make the turkey vulture hissing sound. No parent was in sight, and I couldnt see the second egg. However, I did find the mother or father on the nest with the now fluffy white baby quite often. To my surprise I discovered a second baby on June 12, already white and fluffy, with black head and beak. After that I missed visiting only one day, either walking or bumping over the rough pasture by car toward the woods and nest, a mile from the house. I hoped that both babies could be brought to maturity. The babies seemed to like having their heads rubbed a bit at first. But a wild bird is a wild bird, so all I did was to get as much food as possible from as many sources as possible, hoping to feed the parents, who would feed the young by regurgitation. The turkey vulture is a remarkable bird there is not one thing which it kills, plant or animal. Think how tough it must be for these birds to feed themselves and their babies! I had wonderful help in finding food for the parents. The head of meat and poultry inspection gave permission for butchers to give me scraps not for human consumption. Hugh Bays Food Market in Lancaster was remarkable about keeping Boy (first born, seemed protective) and Girl (shy, always hid behind Boy) I dont pretend to know the true sex of either the best fed, happiest baby buzzards in existence.

The first baby hatched on June 8, a scrawny little thing almost bare even of its covering of white down. It couldnt stand and couldnt even make the turkey vulture hissing sound. No parent was in sight, and I couldnt see the second egg. However, I did find the mother or father on the nest with the now fluffy white baby quite often. To my surprise I discovered a second baby on June 12, already white and fluffy, with black head and beak. After that I missed visiting only one day, either walking or bumping over the rough pasture by car toward the woods and nest, a mile from the house. I hoped that both babies could be brought to maturity. The babies seemed to like having their heads rubbed a bit at first. But a wild bird is a wild bird, so all I did was to get as much food as possible from as many sources as possible, hoping to feed the parents, who would feed the young by regurgitation. The turkey vulture is a remarkable bird there is not one thing which it kills, plant or animal. Think how tough it must be for these birds to feed themselves and their babies! I had wonderful help in finding food for the parents. The head of meat and poultry inspection gave permission for butchers to give me scraps not for human consumption. Hugh Bays Food Market in Lancaster was remarkable about keeping Boy (first born, seemed protective) and Girl (shy, always hid behind Boy) I dont pretend to know the true sex of either the best fed, happiest baby buzzards in existence.  Superintendents of the Highway Patrol for Fairfield and Hocking Counties were great about releasing to me four deer and two raccoons killed by motorists. Although I hate to hear of road kills, I was grateful to be told where I could pick up these. Friends provided groundhogs, and one brought offal from his trout farm. Ben provided blue gills from our lake and helped in some of the highway pickups. Anything small I put near the nest where the family would benefit; but the deer were put in the pasture, attracting turkey vultures and some black vultures from around the area. As I went back and forth through the pasture so many vultures rose from their venison banquet that it seemed to me the supposedly declining population would surely have to go on declining for many years before the turkey vulture could be considered endangered! The latter part of June, Mrs. Anne Bingaman, working with Carl Albrecht, and heading the Wahkeena Natural History Branch, was to band Boy and Girl, but to my amazement she called and said she had found that a law had been passed taking buzzards off the list permitted for banding. The reason turned out to be that a buzzard is a very large bird and the droppings collected on the band turned to concrete. Some birds had died because the circulation of blood had been stopped. My disappointment and Annes turned to excitement when Dave Bittner of the Ohio Department of Natural Resources and manager of the Scioto Trail Civilian Conservation Camp appeared out of the blue on July 2. He had heard about my birds, and I was proud to show them off. A raptor expert, he took Boy and Girl out of the nest and pronounced them well fed and healthy. He told me that there was a new way of banding large raptors and that he would come back in a couple of weeks, when the young would be old enough. He also promised to teach Anne Bingaman the new method.

Superintendents of the Highway Patrol for Fairfield and Hocking Counties were great about releasing to me four deer and two raccoons killed by motorists. Although I hate to hear of road kills, I was grateful to be told where I could pick up these. Friends provided groundhogs, and one brought offal from his trout farm. Ben provided blue gills from our lake and helped in some of the highway pickups. Anything small I put near the nest where the family would benefit; but the deer were put in the pasture, attracting turkey vultures and some black vultures from around the area. As I went back and forth through the pasture so many vultures rose from their venison banquet that it seemed to me the supposedly declining population would surely have to go on declining for many years before the turkey vulture could be considered endangered! The latter part of June, Mrs. Anne Bingaman, working with Carl Albrecht, and heading the Wahkeena Natural History Branch, was to band Boy and Girl, but to my amazement she called and said she had found that a law had been passed taking buzzards off the list permitted for banding. The reason turned out to be that a buzzard is a very large bird and the droppings collected on the band turned to concrete. Some birds had died because the circulation of blood had been stopped. My disappointment and Annes turned to excitement when Dave Bittner of the Ohio Department of Natural Resources and manager of the Scioto Trail Civilian Conservation Camp appeared out of the blue on July 2. He had heard about my birds, and I was proud to show them off. A raptor expert, he took Boy and Girl out of the nest and pronounced them well fed and healthy. He told me that there was a new way of banding large raptors and that he would come back in a couple of weeks, when the young would be old enough. He also promised to teach Anne Bingaman the new method.  On July 7 I found the young out of the nest for the first time fat, healthy, and showing a narrow line of shiny black on the wings, as though someone had used a crayon to edge them. On July 12 both baby buzzards looked beautiful to me, with their white down combined with the new growth of black tail and wing feathers. Boy was even pecking at the sandy, leafy ground outside the nest. Was he just sharpening his beak? I was curious. July 14 was banding day for Boy and Girl. Ed Thomas and Ed Hutchins couldnt come for the banding but would come the following Thursday. Dave Bittner brought three friends with him one who knew about banding, to help. Anne came, but Carl had to miss. With Ben and myself, seven of us were at the scene.

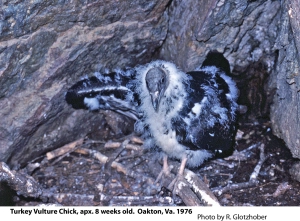

On July 7 I found the young out of the nest for the first time fat, healthy, and showing a narrow line of shiny black on the wings, as though someone had used a crayon to edge them. On July 12 both baby buzzards looked beautiful to me, with their white down combined with the new growth of black tail and wing feathers. Boy was even pecking at the sandy, leafy ground outside the nest. Was he just sharpening his beak? I was curious. July 14 was banding day for Boy and Girl. Ed Thomas and Ed Hutchins couldnt come for the banding but would come the following Thursday. Dave Bittner brought three friends with him one who knew about banding, to help. Anne came, but Carl had to miss. With Ben and myself, seven of us were at the scene.  Both babies were out of the nest, in and out of good hiding places in the rocks. Luckily the experts knew how to catch them, and the buzzards hissing (sounding a great deal like wind through the leaves of trees) helped reveal their whereabouts. I was shown how to hold one, and although I was nervous about breaking one of its legs, I was reassured enough to enjoy my wild one and felt very proud. Dave let me hold one while he snapped the bands on. The bands so large that two are needed to keep the balance were put high on each wing. They are about 1 ½ inches wide by 8 inches long, made of plastic. Boy and Girl are F-39 and F-45, their tags (patagial) white with large black numbers. On July 19 Ed Thomas and Ed Hutchins and his wife, Flo, came as promised. Remembering my lesson, I caught Boy and was able to show him to everyone. Ed Hutchins took pictures, as both Anne and Dave had done before. The babies remained handsome at seven weeks of age, with more black feathers and less white down. Early in August we gave them a second-month-old birthday dinner two pheasants presented to me by a friend who had kept them for three years in her freezer. Twice in August Ben and I found both parents at the nesting site. They flew silently away and watched from nearby trees. We had undoubtedly disturbed feeding of the midday dinner. Both young vultures liked to spend time near good hiding holes on the opposite side of the rock from the nest. One day I watched them exercising their wings. Then on August 8 I sat and watched both on top of the big rock. One walked sedately through a depression while the other flew down to the nest. On August 10 they flew. Sitting in the jeep with Ben, who had driven me over between summer thunderstorms, we looked down the valley, and suddenly both flew by toward the nesting area, dressed in their shiny black first-year feathers and wearing their white shoulder bands. A lovely farewell salute!

Both babies were out of the nest, in and out of good hiding places in the rocks. Luckily the experts knew how to catch them, and the buzzards hissing (sounding a great deal like wind through the leaves of trees) helped reveal their whereabouts. I was shown how to hold one, and although I was nervous about breaking one of its legs, I was reassured enough to enjoy my wild one and felt very proud. Dave let me hold one while he snapped the bands on. The bands so large that two are needed to keep the balance were put high on each wing. They are about 1 ½ inches wide by 8 inches long, made of plastic. Boy and Girl are F-39 and F-45, their tags (patagial) white with large black numbers. On July 19 Ed Thomas and Ed Hutchins and his wife, Flo, came as promised. Remembering my lesson, I caught Boy and was able to show him to everyone. Ed Hutchins took pictures, as both Anne and Dave had done before. The babies remained handsome at seven weeks of age, with more black feathers and less white down. Early in August we gave them a second-month-old birthday dinner two pheasants presented to me by a friend who had kept them for three years in her freezer. Twice in August Ben and I found both parents at the nesting site. They flew silently away and watched from nearby trees. We had undoubtedly disturbed feeding of the midday dinner. Both young vultures liked to spend time near good hiding holes on the opposite side of the rock from the nest. One day I watched them exercising their wings. Then on August 8 I sat and watched both on top of the big rock. One walked sedately through a depression while the other flew down to the nest. On August 10 they flew. Sitting in the jeep with Ben, who had driven me over between summer thunderstorms, we looked down the valley, and suddenly both flew by toward the nesting area, dressed in their shiny black first-year feathers and wearing their white shoulder bands. A lovely farewell salute!